Type 2 diabetes affects about 8% of all adults and is a leading cause of death worldwide. Despite its prevalence, relatively little is known about underlying molecular causes of the disease. SBP researchers now show that defects in a major cell stress pathway play a key role in the failure of pancreatic beta cells, leading to signs of diabetes in mice. The findings, published recently in PLOS Biology, also suggest that a diet rich in antioxidants could help to prevent or treat type 2 diabetes.

“The findings open new therapeutic options to preserve beta cell function and treat diabetes,” said senior study author Randal Kaufman, PhD, director of the Degenerative Diseases Program at SBP. “Because the same cell stress response is implicated in a broad range of diseases, our findings suggest that antioxidant treatment may be a promising therapeutic approach not only for metabolic disease, but also neurodegenerative diseases, inflammatory diseases, and cancer.”

Excess cell stress

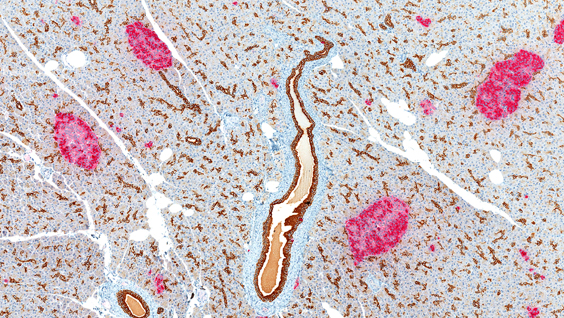

Type 2 diabetes is caused by the failure of pancreatic beta cells to produce enough insulin—a hormone that helps to move a blood sugar called glucose into cells to be stored for energy. A major cause of type 2 diabetes is obesity, which can lead to abnormalities in insulin signaling and high blood glucose levels. Beta cells try to compensate by producing up to 10 times the usual amount of insulin, but this puts extra stress on a cell structure called the endoplasmic reticulum to properly fold, process, and secrete the hormone.

An increase in protein synthesis in beta cells also causes oxidative stress—a process that can lead to cell damage and death through the build-up of toxic molecules called reactive oxygen species. If the stress is too great, the beta cells will eventually fail. Approximately one-third of individuals with abnormal insulin signaling eventually develop beta cell failure and diabetes.

In the new study, Kaufman and his collaborators discovered that beta cell failure is caused by deficiency in a protein called IRE1α, which would otherwise help to protect cells against the stress of increased insulin production. Mice that lacked IRE1α in pancreatic beta cells did not produce enough insulin and developed high blood glucose levels, similar to patients with type 2 diabetes. IRE1α deficiency also caused inflammation and oxidative stress, which was the primary cause of beta cell failure. But treatment with antioxidants, which prevented the production of reactive oxygen species, significantly reduced metabolic abnormalities, inflammation and oxidative stress in these mice.

Taken together, the findings suggest that IRE1α evolved to expand the capacity of beta cells to produce insulin in response to increases in blood glucose levels. The study also implicates this major cell stress pathway in the development of type 2 diabetes and suggests that a diet rich in antioxidants could help to prevent or reduce the severity of the disease.

“Currently, we are testing the effects of antioxidants on glucose levels and beta cell function in mice,” Kaufman said. “If these studies prove successful, they could pave the way for clinical trials in humans and eventually lead to a new therapeutic approach for dealing with a major pandemic of the 21st century.”

This post was written by guest blogger Janelle Weaver, PhD