In the first SBP Insights speaker series, the Institute hosted a doctor, scientist and patient to take a 360-degree look at prostate cancer. Prostate cancer impacts one in nine men, according to the Prostate Cancer Foundation, but the panel experts said the statistic rises dramatically as men get older.

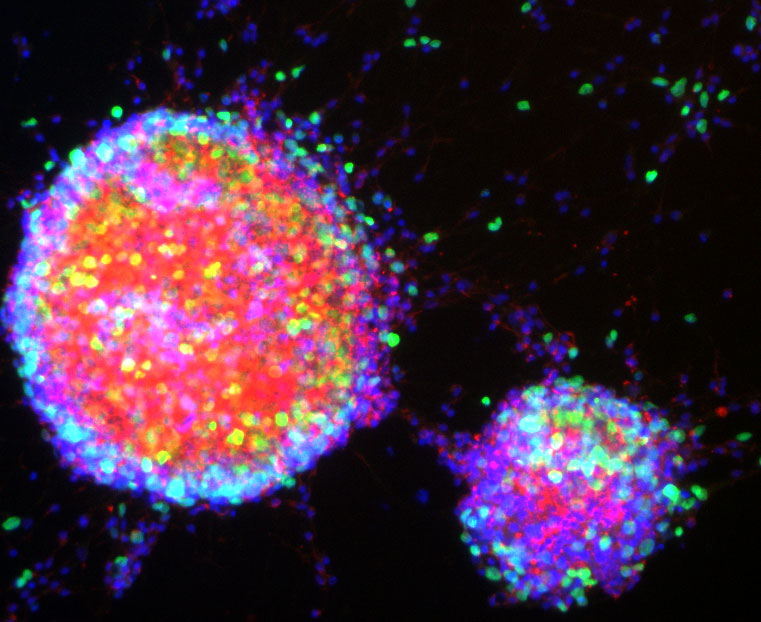

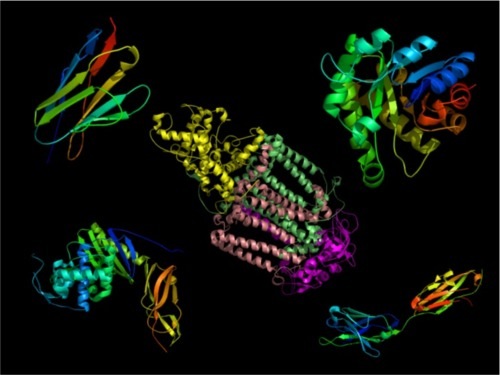

Nick Cosford, PhD, deputy director of SBP’s NCI-designated Cancer Center, discussed how his research is leading to pioneering treatments for advanced prostate cancer by harnessing autophagy (“self-eating” in Greek), a normal physiological process in the body that deals with the destruction of cells.

First diagnosed with prostate cancer more than 20 years ago, SBP Board Chairman Hank Nordhoff shared stories of his own personal experience and how far treatment has progressed since then.

Christopher Kane, MD, senior deputy director of Moores Cancer Center and professor and chair of urology at UC San Diego, gave a clinical perspective on prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment. He shared how if examined closely, nearly half of all 70-year-old men will have low-volume, low-grade prostate cancer. His advice about age and surgical treatments: “You should only have surgery if you can still bring your dad to see me.”

Brad Wills, FOX5 morning weather anchor, moderated the event with great charisma and humor, helping the audience deal with a serious subject in a light-hearted way.

Nearly 90 people from the community attended the unique panel presentation and Q&A, during which audience members had the opportunity to ask the experts about the latest breakthroughs in finding a cure for prostate cancer.

Join us for a unique, 360-degree look at Alzheimer’s disease. The next SBP Insights speaker event takes place on June 5, featuring a panel presentation with leading experts followed by a Q&A. Dr. Jerold Chun, senior vice president of neuroscience drug discovery, Dr. Michael Lobatz, medical director of the Rehabilitation Center at Scripps Memorial Hospital Encinitas, and Serena Reid, a caregiver for an Alzheimer’s disease patient. Kristen Cusato, associate director of the Alzheimer’s Association, will be moderating.