Researchers in the lab of William Stallcup, PhD, professor in SBP’s NCI-designated Cancer Center, in collaboration with scientists at the Institute of Basic Medical Sciences in Beijing, recently made a surprising discovery about the relationship between circulating cholesterol and the development of atherosclerosis.

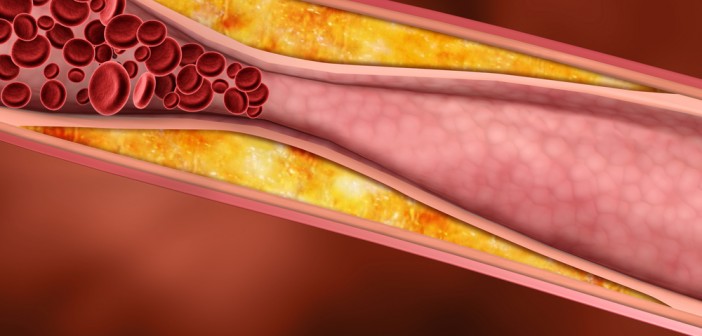

Atherosclerosis, the slow, progressive formation of fatty plaques in artery walls, is accelerated by a number of factors, including obesity and elevated levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL, the so-called “bad cholesterol”).

Having recently shown that mice lacking a protein called NG2 proteoglycan are more likely to become obese and have high levels of LDL in their blood, they suspected that these mice would also be more prone to develop atherosclerosis if fed a high-fat diet. But what they found was quite the opposite.

Surprisingly, they found that obese mice without NG2 proteoglycan had less fatty plaque in their arteries.

The researchers, publishing in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, went on to explain the result by showing that NG2 is present in plaque, specifically in smooth muscle-like progenitor cells. NG2 on these progenitor cells participates in depositing LDL from the blood into phagocytic macrophages to form the foam cells that are characteristic of atherosclerotic plaques. This explains why mice without NG2 have reduced atherosclerosis, even when fed a high fat diet. Without NG2, less LDL gets deposited in foam cells, and plaque build-up is reduced.

Why it’s exciting: According to Zhigang She, MD, PhD, staff scientist and first author of the study, “these results suggest that blocking NG2 may be a promising therapeutic strategy to prevent atherosclerosis. However, since NG2 is normally found in many parts of the body, including the central nervous system, such drugs would have to be very carefully designed.”

To read the paper click here.