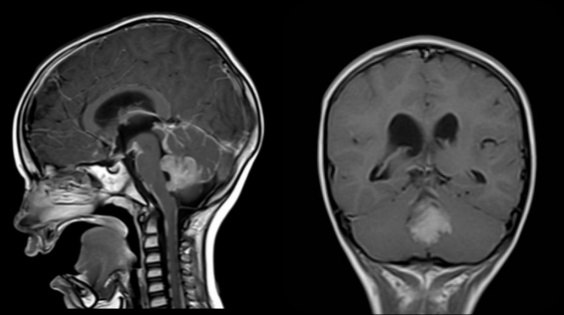

Scientists have long sought to target a cellular receptor called EphA2 because of its known role in many disorders, including cancer, inflammatory conditions, neurological disorders and infectious diseases. However, lack of information about the structure formed when EphA2 links to other molecules—ligands—has hindered drug development.

Now, scientists at Sanford Burnham Prebys have crystallized EphA2 together with peptide ligands (short proteins) and used the structure to engineer more powerful compounds that activate or inactivate the receptor, paving the way for new therapies. The discovery was published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

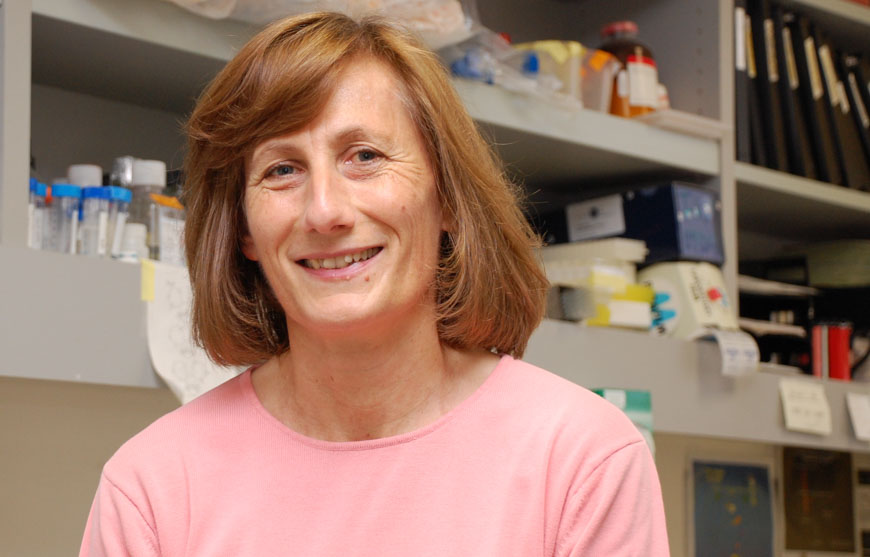

“EphA2 plays a central role in a plethora of biological and disease processes,” says Elena Pasquale, PhD, professor in the Tumor Initiation and Maintenance Program at Sanford Burnham Prebys. “Our team’s identification of potent, highly selective peptides that regulate the receptor is a key step toward rational design of therapies for the numerous disorders that are driven by EphA2.”

EphA2 is found in the cells that line the surfaces of our body, including our skin, blood vessels and other organs. The receptor is typically only present at high levels during disease states, making it a promising drug target. Activating the receptor could hinder tumor growth, while inhibiting it could reduce unwanted formation of blood vessels (angiogenesis), treat certain inflammation-driven disorders and block pathogens—such as malaria, chlamydia and the hepatitis C virus—from gaining entry into a cell through the receptor. Because EphA2 travels deep inside of the cell when activated, scientists could also harness it as a Trojan horse by attaching chemotherapies or imaging agents to the peptide ligands, which would subsequently be delivered to the desired cells.

In the study, the scientists initially crystallized a weakly binding peptide in complex with EphA2, yielding a detailed picture of the binding features and providing clues to the receptor’s “sweet spot” or site of action. The researchers then used this information to repeat this process, engineering increasingly more powerful ligands. This work identified several peptides that strongly clasp the receptor and activate or inactivate it—which can be used to inform drug development.

Further quantitative Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) microscopy experiments, which measure receptor-receptor interactions, revealed that EphA2 receptors cluster together when activated by a peptide—an effect similar to that caused by its natural ligands—answering an unresolved question in the field.

“In addition to helping guide therapeutic development paths, these peptides are also valuable research tools for scientists who are working to gain insights into this important receptor,” adds Pasquale. “Our hope is that with this new information, one day we can find targeted therapies to treat cancer, inflammatory disorders and infectious diseases that are regulated by EphA2.”

The co-first authors of the study are Maricel Gomez-Soler, PhD, and Marina Petersen Gehring, PhD, of Sanford Burnham Prebys; and Bernhard C. Lechtenberg, PhD, formerly of Sanford Burnham Prebys and currently of the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research.

Additional authors include Elmer Zapata-Mercado and Kalina Hristova, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University. The study’s DOI is 10.1074/jbc.RA119.008213.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01NS087070, R01GM131374 and P30CA030199).