This post was written by Janelle Weaver, PhD, a freelance writer

Heart disease is the number one killer in the United States and a major cause of disability. One major risk factor is obesity, which itself has undergone a dramatic increase in prevalence in the United States over the past 20 years and now affects more than one-third of adults. A major challenge in developing targeted drugs for diet-induced heart disease is to understand how molecular and genetic changes trigger metabolic imbalances that ultimately impair heart function.

Sanford-Burnham researchers have shed new light on this question in a study published March 5 in Cell Reports, revealing a key genetic pathway in the intricate network of regulatory mechanisms that is likely to also contribute to obesity-related heart disease in humans. “For the very first time, we were able to understand how multiple genes—all key components of metabolic regulation—were modulated by a high-fat diet and interact with each other to cause a condition called lipotoxic cardiomyopathy, as revealed by this genetic model,” said senior study author Rolf Bodmer, PhD, professor and director of the Development, Aging, and Regeneration Program at Sanford-Burnham.

“The emergence of a detailed network of genes we described could pave the way for the development of drugs to combat this serious public health problem,” said Daniel Kelly, M.D., scientific director of Sanford-Burnham’s Lake Nona, Fla., campus. “From our studies in mammalian systems we knew that individual components were important metabolic regulators, but this new study, taking advantage of a simple model organism, links them into a genetic pathway that now can be tested for mediating lipotoxicity in the mammalian heart.“

Unraveling the gene network

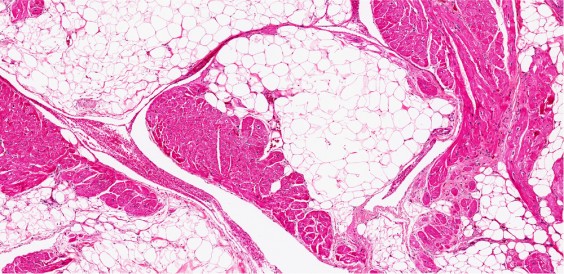

Obesity and diabetes are associated with an increased risk of a form of cardiac dysfunction called lipotoxic cardiomyopathy, which is caused by excessive accumulation of lipids in the heart. Obesity and diabetes have also been linked to abnormalities in a protein called PGC-1α, which regulates the expression of genes involved in energy metabolism. Although PGC-1α has also been implicated in cardiac lipid accumulation and heart failure in mice, it has not been clear whether or how this protein interacts with other metabolic regulators and signaling pathways to modulate the deleterious effects of a high-calorie diet on lipid accumulation and cardiomyopathy.

Bodmer and his team set out to answer these questions in the new study. Their findings suggest that a high-fat diet promotes fat accumulation by interfering with the function of PGC-1/spargel—a gene that encodes the PGC-1 homologue in fruit flies. By increasing the activity of PGC-1/spargel, the researchers blunted the effects of a high-fat diet on lipid accumulation and cardiac dysfunction. They also identified several other key metabolic regulators that interact with PGC-1/spargel and play an important role in diet-induced heart dysfunction.

“Given the high degree of gene conservation during evolution between the fly and mammals, this gene network is highly relevant for understanding obesity and associated diseases like heart disease in humans,” said first study author Soda Diop, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Bodmer’s lab.

In humans, cardiomyopathy is a disease in which the heart muscle becomes enlarged, thicker, and more rigid than normal. It can make the heart less able to pump blood through the body, potentially leading to serious complications such as heart failure, abnormal heart rhythms, and sudden cardiac arrest.

“By further dissecting the network of genes involved in controlling cellular processes leading to lipotoxic cardiomyopathy, we hope to reveal additional targets for the development of drugs for this life-threatening condition,” added Bodmer.

Click here to read the paper in full.