Better therapies for acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a fast-growing cancer of the bone marrow, are urgently needed. Nearly 15,000 people in the United States are diagnosed with AML each year, and it’s the most common acute leukemia in adults. The cause of the disease is unknown, and it is usually fatal within the first five years.

New research from a team including SBP scientists shows that a novel strategy to induce cancer cell ‘suicide’ may help AML patients. Guy Salvesen, PhD, professor in SBP’s NCI-designated Cancer Center and dean of the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences, and Mario Navarro, PhD, postdoctoral fellow in Salvesen’s lab, shared their expertise in cell death with collaborators at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research (WEHI) in Melbourne, Australia, to this important study published in Science Translational Medicine.

This new suicide strategy turns on a different cell death program from the one triggered by current anticancer drugs. Available therapeutics that cause tumor cells to break down and die—a process called apoptosis—are often ineffective because the apoptosis machinery is disabled.

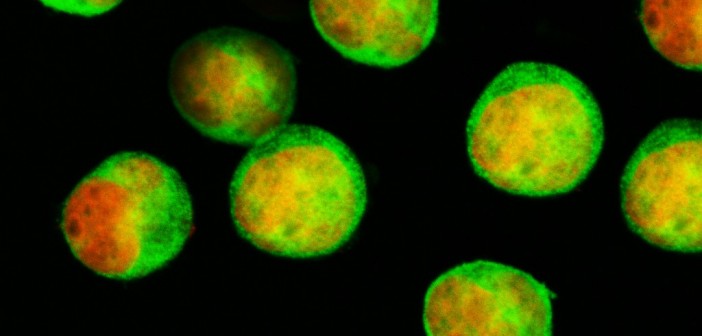

Salvesen and the researchers at WEHI saw a workaround, at least for certain cancers. Some cell types, including immune cells and their precursors in bone marrow, can also eliminate themselves through another process called necroptosis. This phenomenon, defined only in the last decade, is like a controlled cellular explosion, while apoptosis keeps cell contents inside ‘blebs’ of the cell membrane.

“We knew that necroptosis can be induced in vitro by treating cells with two drugs—a SMAC mimetic and a caspase-8 inhibitor,” said Salvesen. “The question here was whether those drugs would also kill cancer in vivo.”

Testing of the drug combination in mice shows that they do.

“When used together, these two drugs are surprisingly effective. Our collaborators showed that, while untreated mice had tumor cells basically everywhere, none were detectable in those given both drugs,” added Salvesen. “These findings are especially exciting since there have been no treatment breakthroughs in AML in decades.”

However, a clinical trial isn’t imminent. Because the caspase-8 inhibitor used (emricasan) has a very short lifetime in the body, a better caspase-8 inhibitor will likely need to be developed first.

“This work is a great example of how institute-wide collaborative agreements like the one between SBP and WEHI can facilitate high-impact science,” Salvesen said.

The paper is available online here.