Sanford Burnham Prebys’ Publications

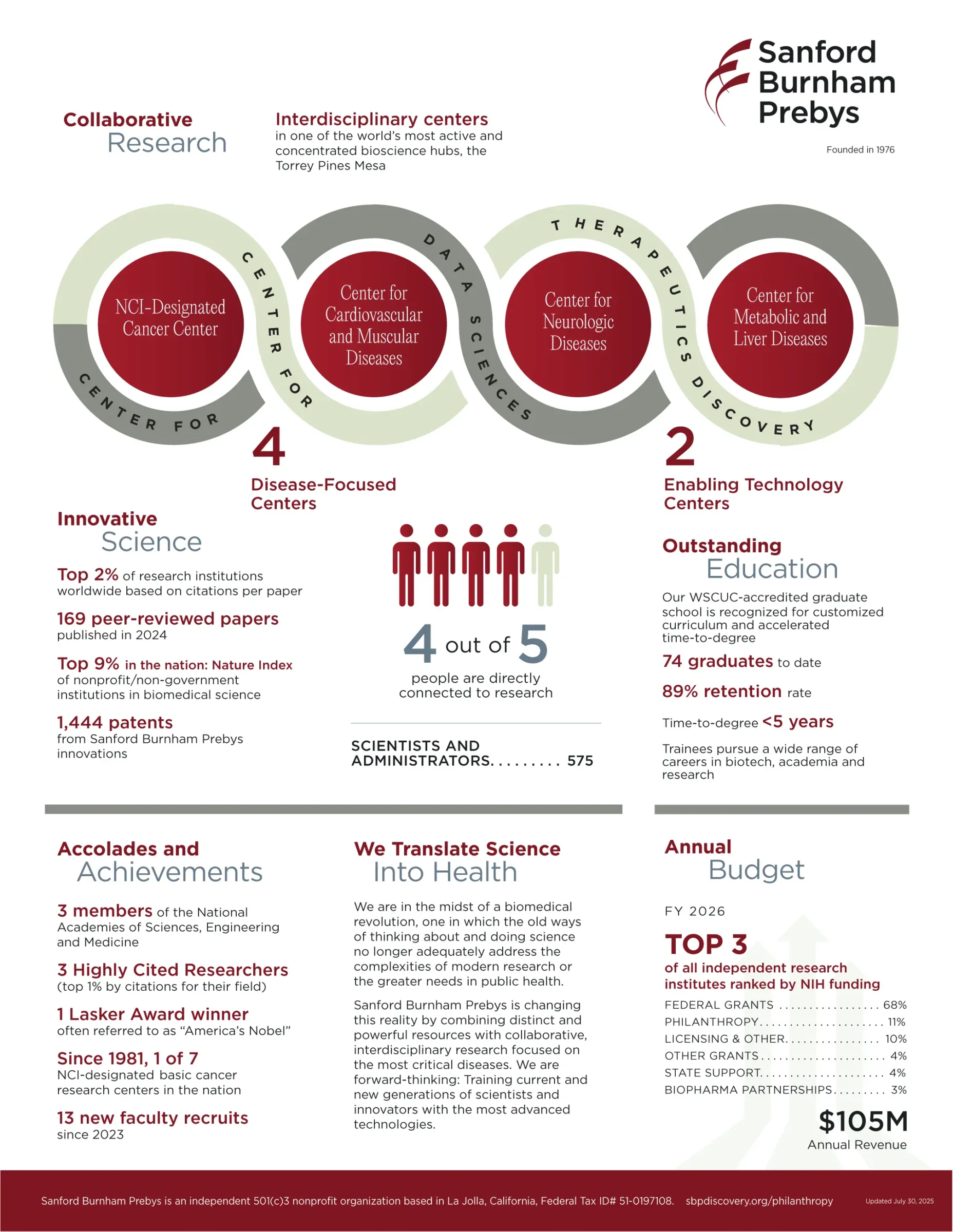

Sanford Burnham Prebys produces a range of publications that reflect the Institute’s scientific achievements, community impact, and ongoing commitment to biomedical discovery. This page provides access to current and archived materials that showcase the Institute’s impact and ongoing initiatives.

Discoveries Newsletter

Delivered monthly, Discoveries shares timely updates from Sanford Burnham Prebys, including research breakthroughs, Institute news, and stories that illustrate the real-world impact of our science. It offers readers an inside look at how discovery drives our mission.

Pathways Magazine

Pathways is Sanford Burnham Prebys’s flagship magazine, featuring in-depth stories about our science, people, and impact. While currently on hiatus, Pathways remains a valuable archive of past features that showcase the breadth and depth of our research enterprise.

Contact Media Relations

Sanford Burnham Prebys welcomes media inquiries. Our communications team is available to support journalists at the local, national, and international levels by providing information about our research and experts. We can facilitate interviews with Sanford Burnham Prebys scientists and help develop compelling story ideas.

Scott LaFee

Vice President, Communications

Office: (858) 795-5055

Cell: (619) 889-2368

slafee@sbpdiscovery.org

Liz Hincks

Director of Communications

Office: (858) 795-5012

Cell: (619) 609-9429

ehincks@sbpdiscovery.org

Greg Calhoun

Science Writer

Cell: (586) 530-9706

gcalhoun@sbpdiscovery.org