Resources for the Press and Media

Sanford Burnham Prebys welcomes media inquiries. Our communications team is available to support journalists at the local, national, and international levels by providing information about our research and experts. We can facilitate interviews with Sanford Burnham Prebys scientists and help develop compelling story ideas.

On this page you will find photos of our researchers, technologies, buildings, leadership, as well as science images. The resources on this page can be used by third parties, but we ask that all images are credited to Sanford Burnham Prebys or other sources where noted.

Logo

While use of the full color logo is preferred, several approved alternates are available when black and white or one-color applications are required.

Contact Media Relations

Sanford Burnham Prebys welcomes media inquiries. Our communications team is available to support journalists at the local, national, and international levels by providing information about our research and experts. We can facilitate interviews with Sanford Burnham Prebys scientists and help develop compelling story ideas.

Scott LaFee

Vice President, Communications

Office: (858) 795-5055

Cell: (619) 889-2368

slafee@sbpdiscovery.org

Liz Hincks

Director of Communications

Office: (858) 795-5012

Cell: (619) 609-9429

ehincks@sbpdiscovery.org

Greg Calhoun

Science Writer

Cell: (586) 530-9706

gcalhoun@sbpdiscovery.org

Image Library

Campus Photos

Sanford Burnham Prebys monument sign

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Bradley Innovation Plaza

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

The Conrad Prebys Center for Chemical Genomics

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Chairmen’s Hall courtyard outside Building 5

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Chairmen’s Hall in Building 5

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Chairmen’s Hall in Building 5

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Exterior view of Building 12

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Aerial view of Building 12

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Ruoslahti Way

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

Ruoslahti Way near Buildings 6 and 7 at Sanford Burnham Prebys. This location honors former director Erkki Ruoslahti, MD, PhD, whose accolades include the 2022 Lasker Basic Medical Research Award, sometimes called “America’s Nobel.”

Campus aerial view from north

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

Aerial view from north of the Sanford Burnham Prebys campus in La Jolla.

Campus aerial view from northeast

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

Aerial view from north and east of the Sanford Burnham Prebys campus in La Jolla.

Campus aerial view from east

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

Aerial view from east of the Sanford Burnham Prebys campus in La Jolla.

Laboratory Photos

Scientist works at a laboratory bench

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

A scientist works at a laboratory bench in Building 12 on the Sanford Burnham Prebys campus.

Scientist conducts neuroscience research

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

A scientist conducts neuroscience research in the lab of Jerold Chun, MD, PhD, a professor in the Degenerative Diseases Program at Sanford Burnham Prebys.

Graduate student removes samples from storage in a liquid nitrogen tank

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

A graduate student removes samples from storage in a liquid nitrogen tank. She conducts aging research in the lab of Caroline Kumsta, PhD, an assistant professor in the Development, Aging and Regeneration Program at Sanford Burnham Prebys.

Scientists at work at the Conrad Prebys Center for Chemical Genomics

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

Scientists at work at the Conrad Prebys Center for Chemical Genomics at Sanford Burnham Prebys. The center’s team applies extensive pharmaceutical drug discovery experience toward the goal of finding and testing new drugs and therapies that benefit patients.

Scientists at work at the Conrad Prebys Center for Chemical Genomics

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

Scientists at work at the Conrad Prebys Center for Chemical Genomics at Sanford Burnham Prebys. To screen up to 750,000 chemicals to find new drug candidates, highly miniaturized arrays are used in which 1536 tests are conducted in parallel. Experiments are miniaturized to such an extent that hand pipetting is not possible and acoustic dispensing (i.e. sound waves) is used to precisely move the tiny amounts of liquid in a touchless, tipless automated process.

Researchers collaborate in the lab of Sanju Sinha, PhD

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

Researchers collaborate in the lab of Sanju Sinha, PhD, an assistant professor in the Cancer Molecular Therapeutics Program at Sanford Burnham Prebys. Sinha (second from right) and his lab work to develop computational tools that can analyze data from thousands of people to find out why healthy cells become cancerous. Their goal is to guide the development of new treatments.

Scientist draws chemical structural diagrams on a fume hood

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

A scientist draws chemical structural diagrams on a fume hood that captures and removes vapors to ensure safety during experiments conducted at Sanford Burnham Prebys.

Scientist working with zebrafish

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

A scientist working with zebrafish housed in tanks at Sanford Burnham Prebys. Researchers at the Institute use zebrafish to study diseases such as the liver condition called Alagille syndrome because these fish are vertebrates with similar organ development to humans. Zebrafish enable scientists to use experimental approaches that aren’t possible with other disease models.

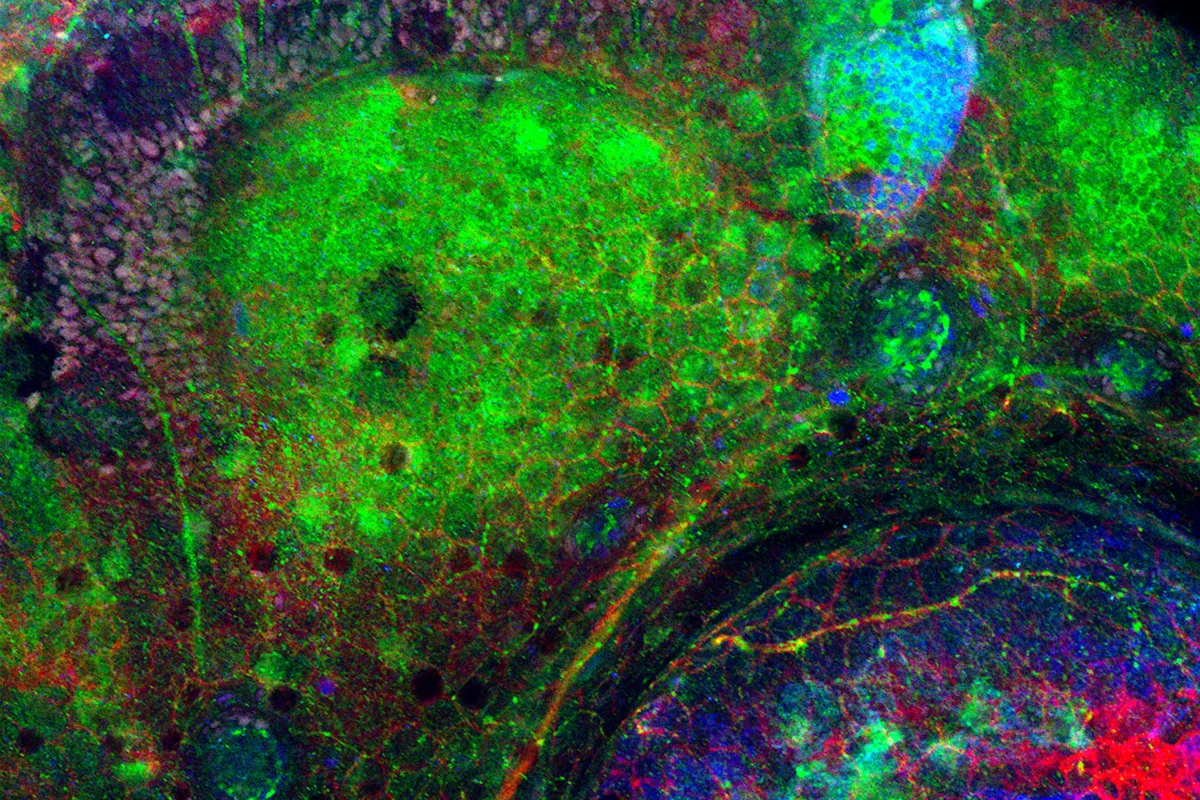

Scientific Images

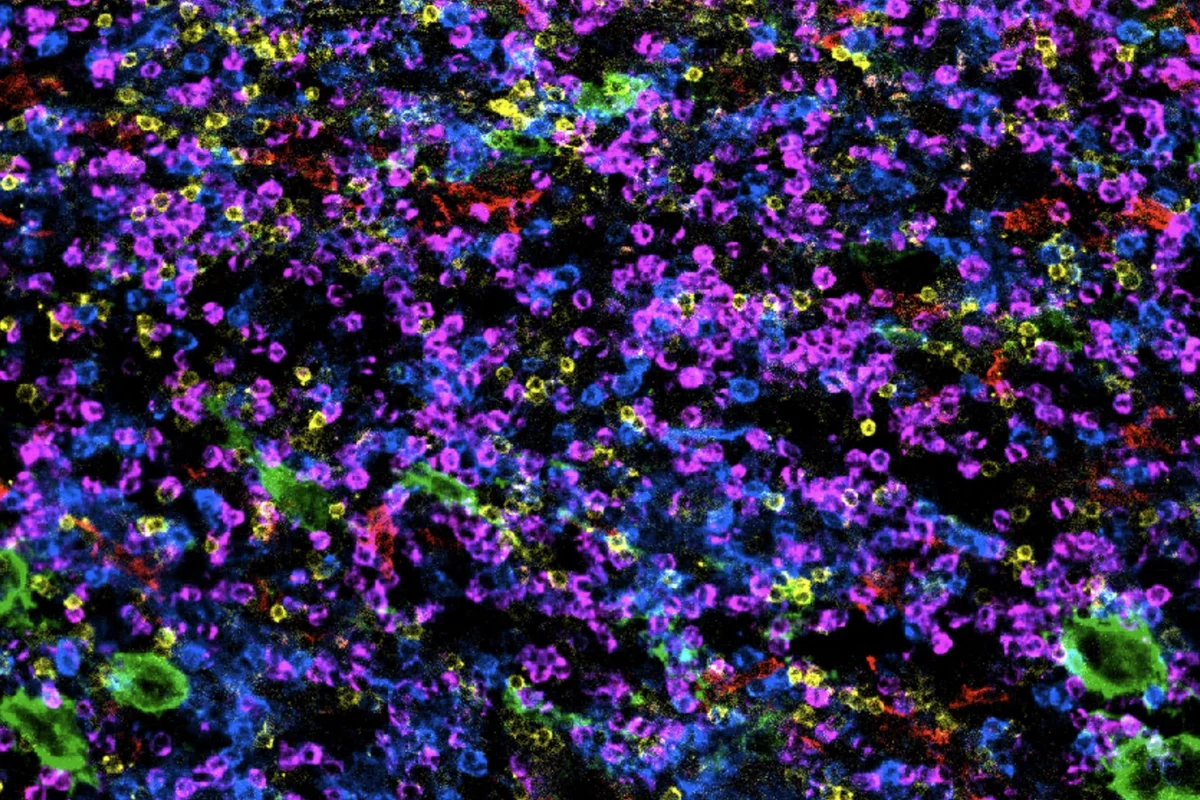

A spectrum of immune cells

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys | Beatrice Silvestri, Wang Lab

Full caption

Immune cells are defenders of our bodies. This micrograph shows the diversity of immune cells in the bone marrow, where they are born and mature. Each color represents a specialized immune cell type, captured by state-of-the-art highly multiplexed microscopy and methods developed at Sanford Burnham Prebys.

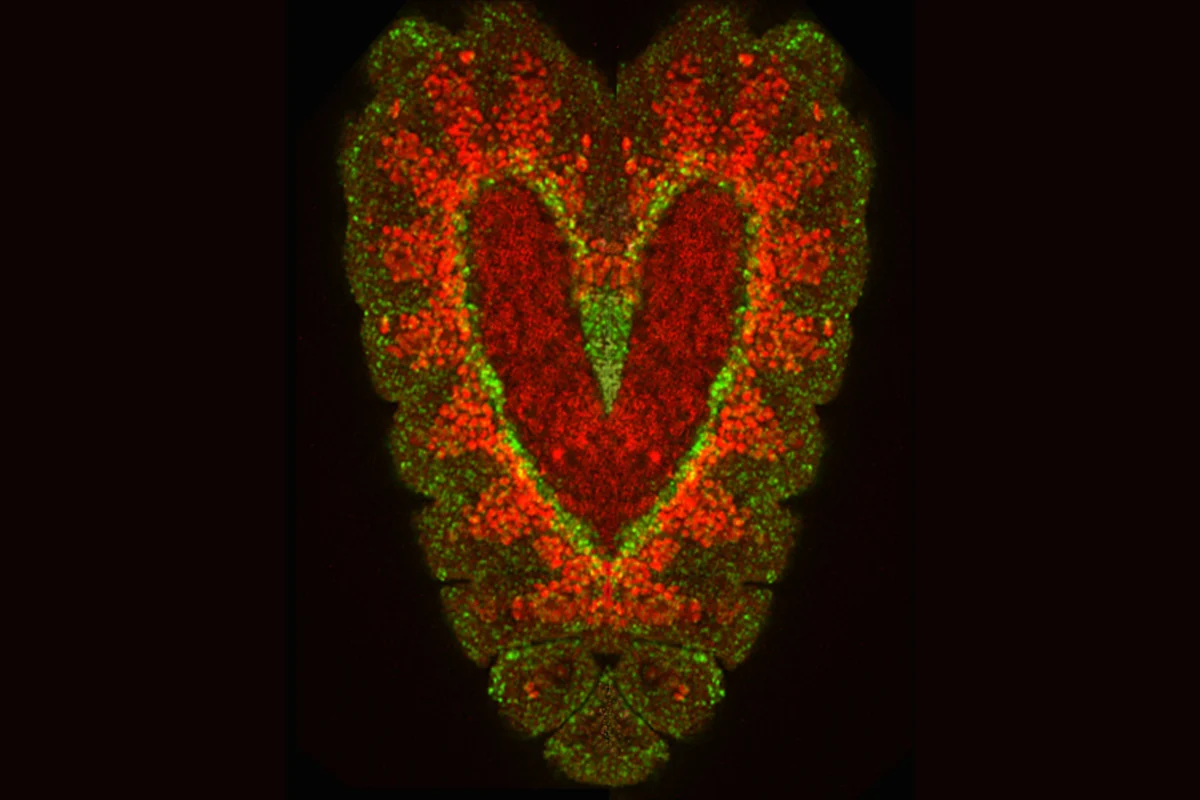

Drosophila heart composite

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys | Susan Klined and Rolf Bodmer

Full caption

Two embryos of the Drosophila fruit fly labeled with fluorescent dyes and overlapped in a composite image to form a heart shape. The interior cells labeled in green are destined to become myocytes—the muscle cells of the heart.

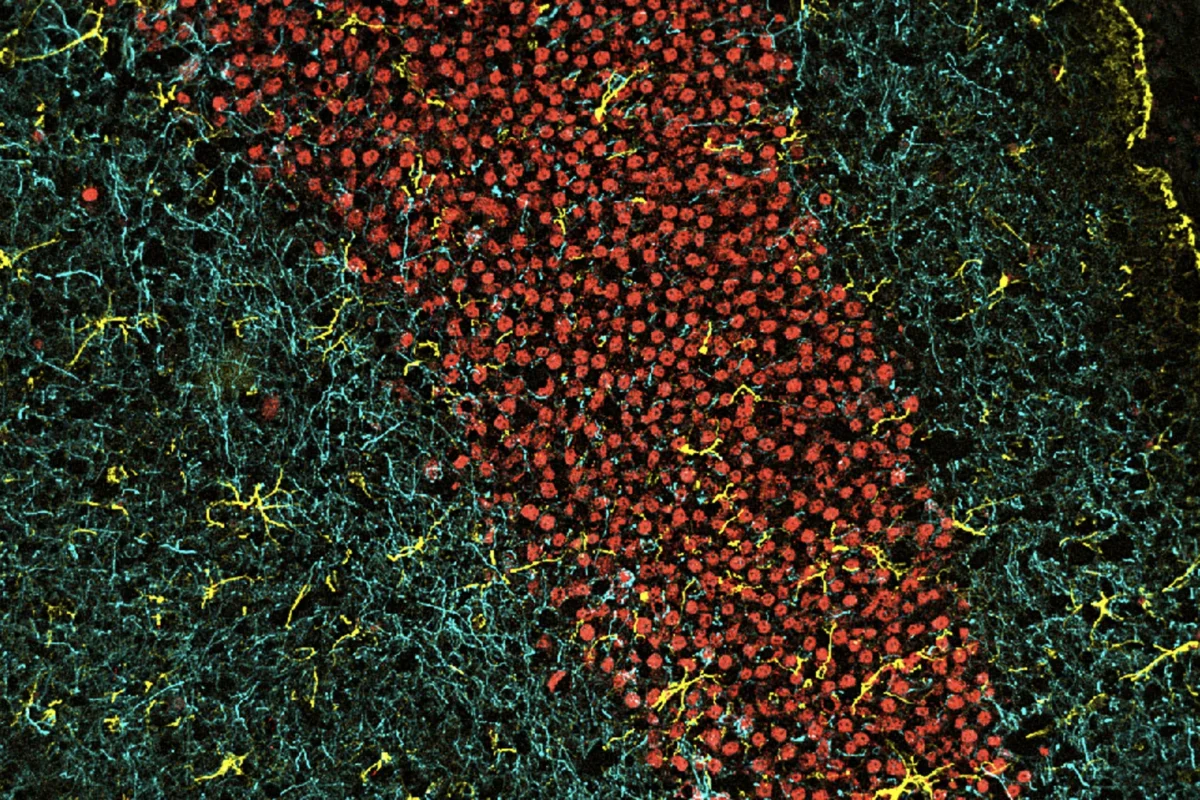

Connections in the brain

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys | Sara Ancel and Annanya Sethiya, Wang Lab

Full caption

The brain is composed of billions of connections. Pictured are a group of neurons (their nuclei in red), the complexity of axon projections (labeled in cyan), and supportive astrocytes (labeled in yellow) from the hippocampus region of a murine brain.

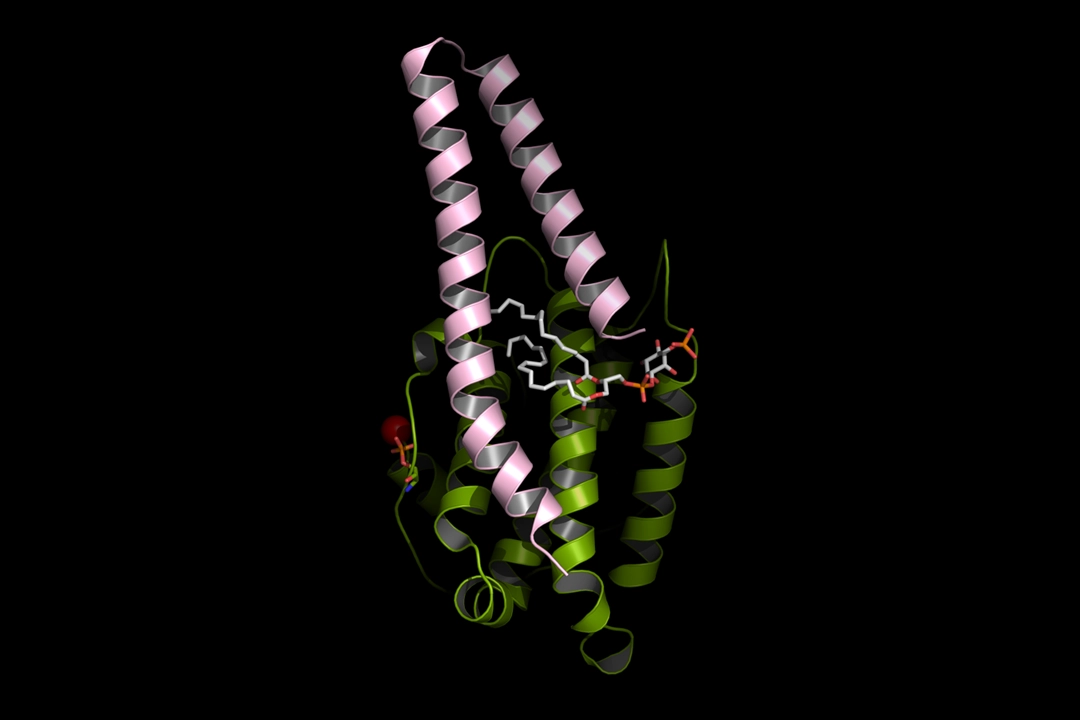

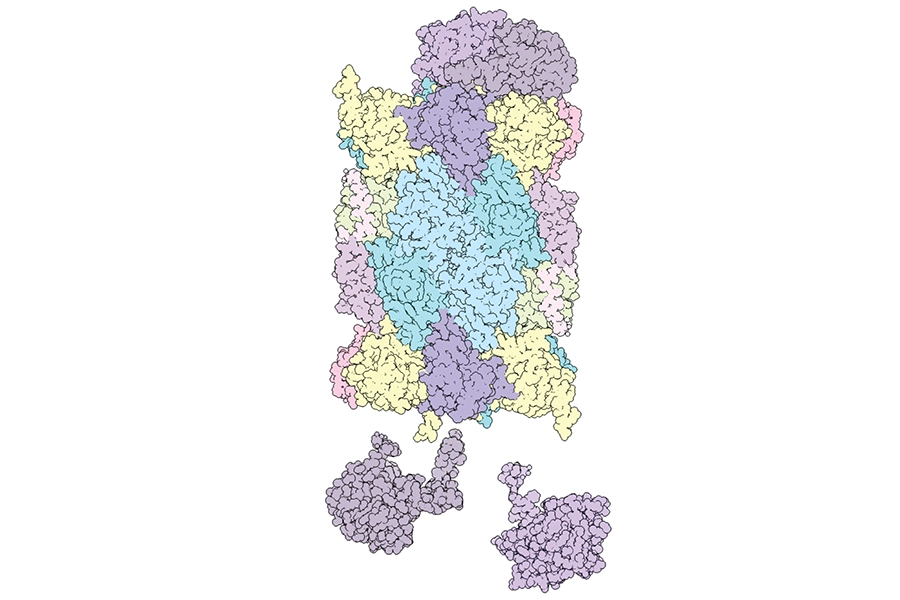

Hippo pathway – cell membrane lipid

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys | Brooke Emerling

Full caption

Scientists at Sanford Burnham Prebys used AlphaFold 2 software to simulate docking between a component of the hippo pathway and a cell membrane lipid. The hippo pathway is dysregulated in cancer, but scientists have found it very difficult to develop drugs that directly target it. Targeting the pathway indirectly through a specific cell membrane lipid may lead to new treatments for cancers with abnormal hippo signaling.

This image was included on the cover of Science Signaling in May 2024.

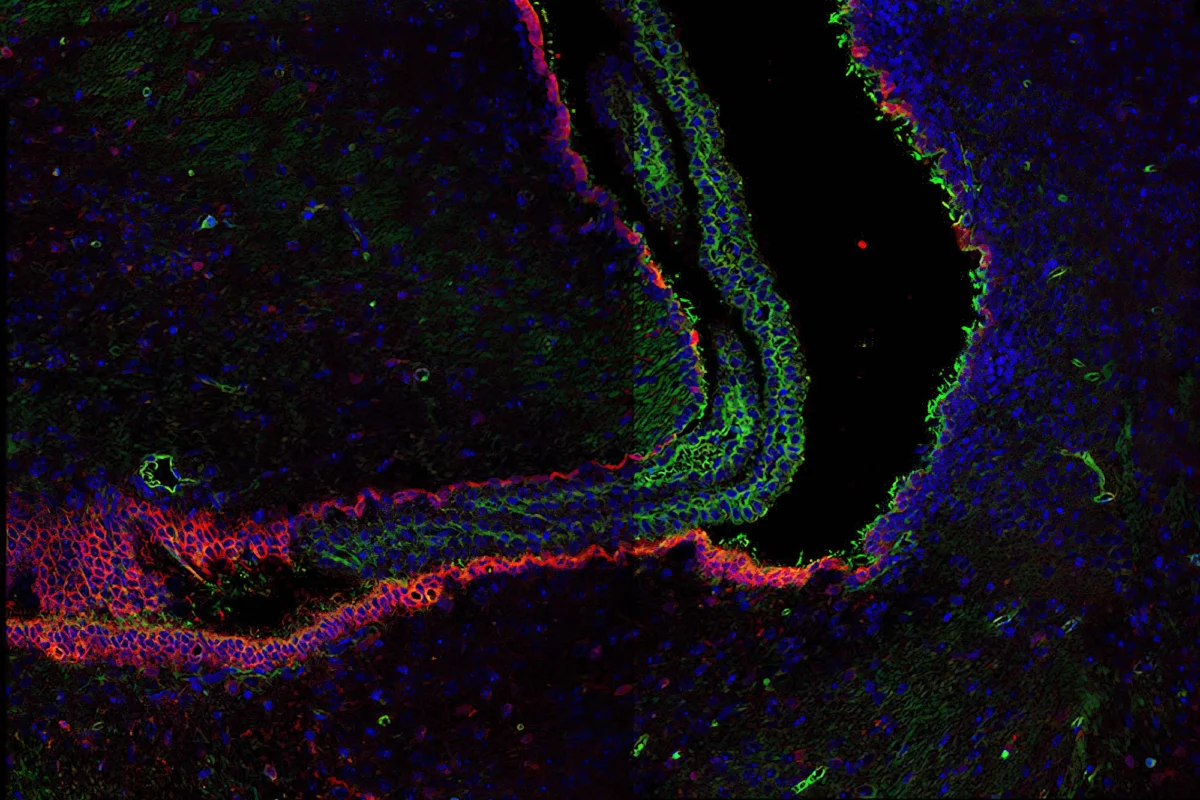

Hydrocephaly – excess cerebrospinal fluid

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys | Nicole Lummis, Chun Lab

Full caption

When there is too much cerebrospinal fluid in the brain, the fluid-filled ventricles depicted in black expand. This neurological disorder is known as hydrocephaly. The blood vessels that make cerebrospinal fluid are shown in blue, and they are lined with cells displayed in red that possess green fibers responsible for moving the fluid around the brain. Scientists at Sanford Burnham Prebys are studying how fats released in cerebrospinal fluid due to severe bleeding may lead to issues with brain development, including hydrocephaly.

Neurodegeneration – zebrafish embryo brain

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys | Keith Gates, Dong Lab

Full caption

The brain sections of zebrafish embryos help scientists at Sanford Burnham Prebys study disorders that cause the brain to deteriorate over time.

Proteasome

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys | Jianhua Zhao

Full caption

A 3D rendering of a proteasome. An estimated 80% of proteins within the cell are degraded by proteasomes to maintain a healthy balance as new proteins replace those that have fulfilled their function or became misfolded and potentially harmful. Issues with proteasomes can contribute to certain cancers and are associated with age-related diseases, so a better understanding of how these prodigious protein degraders are made may lead to new treatments for many conditions.

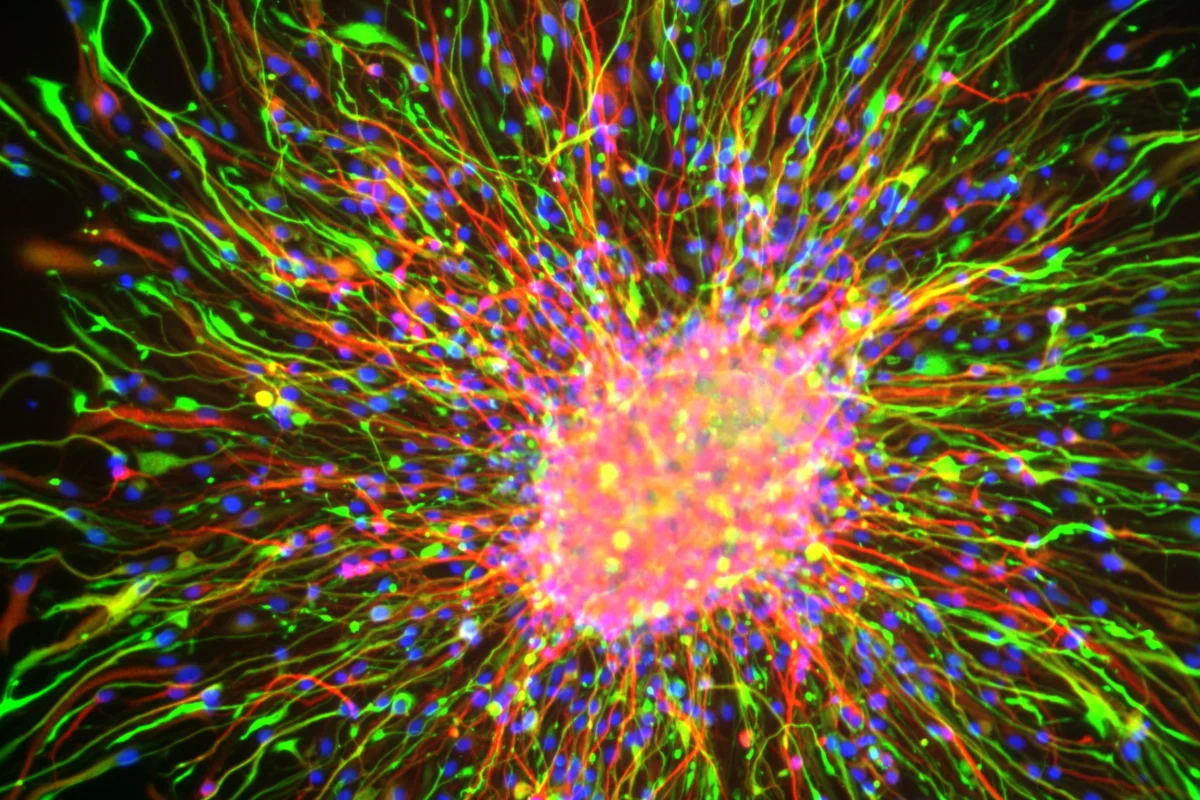

Starburst of neural rosette cells

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys | Brandon Nelson

Full caption

A view of the differentiation of neural rosette cells into more mature cell types. Neural rosette cells can become any type of neural cell: neurons, oligodendrocytes and astrocytes. The cell nuclei are labeled in blue.

People Photos

Leaders and Namesakes

T. Denny Sanford

Honorary Trustee, Institute Namesake

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

T. Denny Sanford is Chairman and CEO of United National Corp. as well as owner and founder of First Premier Bank. He is an honorary trustee of Sanford Burnham Prebys with a long-standing relationship with the institute. In 2023, Sanford provided support for the Institute to recruit up to 20 new faculty positions in research areas including cancer, neurodegeneration and computational biology.

Malin Burnham

Honorary Trustee, Institute Namesake

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

Malin Burnham is an honorary trustee of Sanford Burnham Prebys and has served on the institute’s board since 1982. In 1996, Sanford Burnham Prebys’ predecessor, the La Jolla Cancer Research Foundation, was renamed The Burnham Institute after he and an anonymous donor contributed $10 million.

Conrad Prebys

Institute Namesake

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

Conrad Prebys (August 20, 1933 – July 24, 2016) was a longtime supporter of Sanford Burnham Prebys and namesake in honor of his landmark $100 million gift in 2015. In addition to the 2015 donation, Prebys gave a substantial sum to establish the Conrad Prebys Center for Chemical Genomics in 2009, as well as regular gifts supporting the Institute’s research in the intervening years.

T. Denny Sanford, Malin Burnham and Conrad Prebys

Institute Namesakes

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

T. Denny Sanford, Malin Burnham and Conrad Prebys are the institute’s namesakes. They have generously invested in the Sanford Burnham Prebys mission of translating science into health.

David Brenner, MD

President and CEO

Donald Bren Chief Executive Chair

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

David Brenner, MD, was named president and chief executive officer of Sanford Burnham Prebys in September 2022 after serving as vice chancellor for health sciences at UC San Diego and dean of its school of medicine for an unprecedented 15 years, during which he oversaw the launch and expansion of numerous multidisciplinary efforts, including the Institute for Engineering in Medicine, the Institute for Genomic Medicine, the Sanford Consortium for Regenerative Medicine, the UC San Diego Sanford Clinical Stem Cell Program, and the C3 Cancer Center Consortium (comprising UC San Diego, the Salk Institute for Biological Studies and Sanford Burnham Prebys).

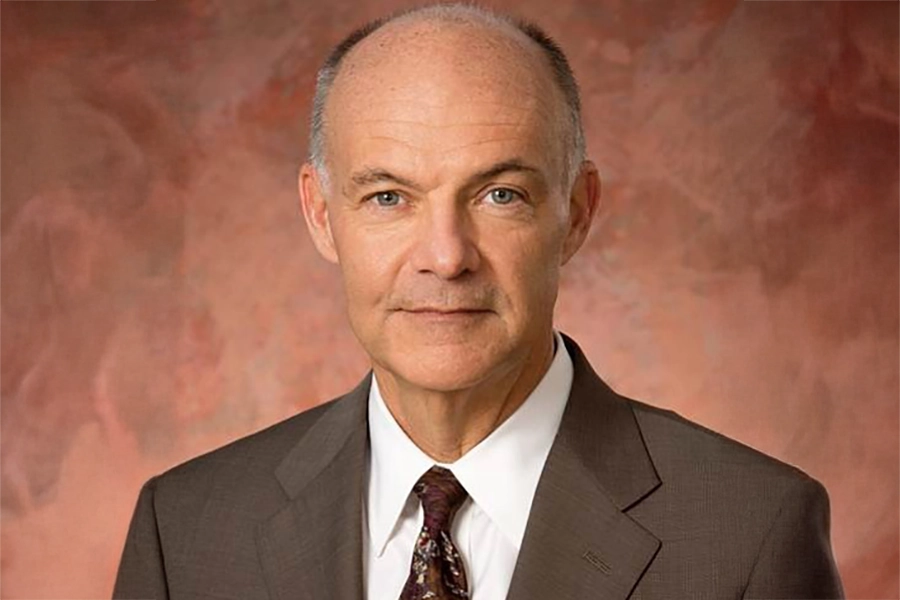

Donald Kearns, MD

Chair, Board of Trustees

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

Donald Kearns, MD, serves as chair of the Sanford Burnham Prebys Board of Trustees, and has served on the board since 2020. He is president emeritus of Rady Children’s Hospital-San Diego, having previously served as president and CEO from 2013 to 2018.

Center Directors

Cosimo Commisso, PhD

Interim Director, Deputy Director, NCI-designated Cancer Center

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

Cosimo Commisso, PhD, is the deputy director of the National Cancer Institute-designated Cancer Center at Sanford Burnham Prebys. He currently serves as the interim director while a national search is conducted for a new center director.

Rolf Bodmer, PhD

Director, Center for Cardiovascular and Muscular Diseases

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

Rolf Bodmer, PhD, is the director of the Sanford Burnham Prebys Center for Center for Cardiovascular and Muscular Diseases. He also is a professor in the Development, Aging and Regeneration Program.

Su-Chun Zhang, MD, PhD

Director, Center for Neurologic Diseases

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

Su-Chun Zhang, MD, PhD, was appointed director of the Sanford Burnham Prebys Center for Neurologic Diseases in November 2024. Prior to joining the institute, he was the Steenbock Professor of Behavioral and Neural Sciences, Neuroscience and Neurology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Waisman Center.

Michael Jackson, PhD

Director, Conrad Prebys Center for Chemical Genomics

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

Michael Jackson, PhD, is the director of the Conrad Prebys Center for Therapeutics Discovery at Sanford Burnham Prebys. He also is the Senior Vice President of Drug Discovery and Development for the Institute’s Conrad Prebys Center for Chemical Genomics.

David Brenner, MD

Interim Director, Center for Metabolic and Liver Diseases

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

David Brenner, MD, is the interim director of the Center for Metabolic and Liver Diseases at Sanford Burnham Prebys. He is also the president and chief executive officer.

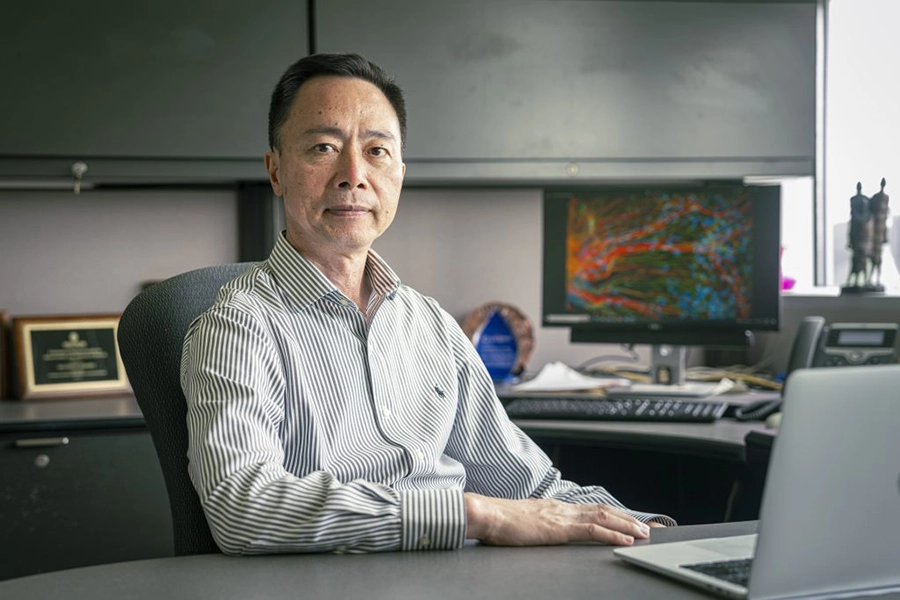

Yuk-Lap (Kevin) Yip, PhD

Interim Director, Center for Data Sciences

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

Kevin Yip PhD, is the interim director of the Center for Data Sciences at Sanford Burnham Prebys.

Program Leaders

Peter D. Adams, PhD

Director, Cancer Genome and Epigenetics Program

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

Peter D. Adams, PhD, is the director of the Sanford Burnham Prebys Cancer Genome and Epigenetics Program.

Brooke Emerling, PhD

Director, Cancer Metabolism and Microenvironment Program

Credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys

Full caption

Brooke Emerling, PhD, is the director of the Sanford Burnham Prebys Cancer Metabolism and Microenvironment Program.