Up to 80 percent of people who have had diabetes for more than 20 years develop diabetic retinopathy, putting them at risk for major vision loss. Current treatments for this complication have major drawbacks—laser therapy can cause blind spots, and biologic drugs are expensive.

A new study published in the journal Science Translational Medicine reveals new steps in the development of diabetic retinopathy and shows that they can be prevented using targeted drugs. Randal Kaufman, PhD, professor and director of the Degenerative Diseases Program, contributed to the research, the result of a long-term association with study leaders Przemyslaw Sapieha, PhD, and Frédérick A. Mallette, PhD, at Maisonneuve-Rosemont Hospital and the Université de Montréal.

“These findings fill in a major gap in our understanding of how retinopathy progresses and provide unprecedented insight into how we could slow vision loss caused by this often devastating disease,” said Kaufman. “Before, we knew what happened to the retina, but we didn’t know what was happening inside its cells. Now therapies can be developed to address earlier events in the pathology.”

What is diabetic retinopathy?

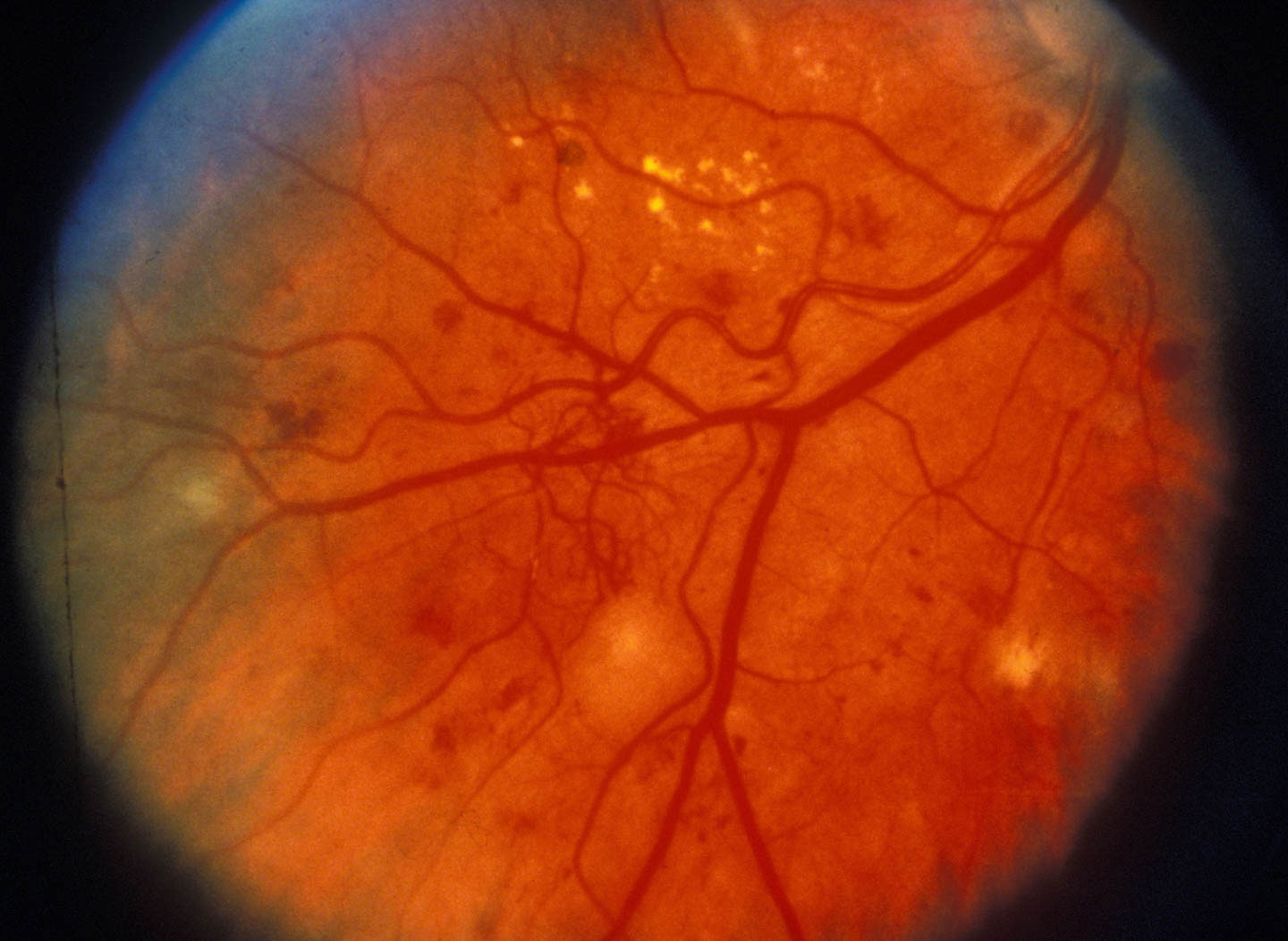

Repeated episodes of high blood sugar caused by diabetes can damage the small blood vessels that supply the retina, causing visible microaneurysms and, at later stages, fluid leakage into the space below the retina. When those vessels become totally blocked, weaker blood vessels form, but in the wrong place—into the interior of the eye. These new vessels cause vision loss by leaking blood, which blocks light, and inducing scars to form, which can pull the retina away from the back of the eye. Current therapies destroy the leaky vessels and keep more from growing.

What steps did they uncover?

The researchers wanted to understand how retinal cells survive the initial vascular damage, and found that they go into a self-preservation mode called senescence. One aspect of the senescence program is secretion of molecules that promote tissue repair, including pro-vessel growth factors and cytokines.

How could these discoveries lead to new treatments?

The study identified two potential strategies for blocking retinopathy. First, the initiation of senescence can be blocked using inhibitors of inositol-requiring enzyme 1 alpha (IRE1alpha, discovered by Kaufman 20 years ago), which are currently being developed by pharmaceutical companies as anti-cancer treatments. Second, the secretion of growth factors and cytokines can be counteracted with eye injections of an available drug, metformin, currently used in pill form to treat type 2 diabetes.

“Modulating senescence is a totally new way to treat retinopathy,” Kaufman commented. “In this study in mice, it appears not only to prevent the growth of leaky vessels, but also to promote repair of the original ones. The findings suggest that this strategy could be even better than current treatments at slowing the advance of the disease, or even enhance patients’ vision. Further research is needed to determine the best way to keep retinal cells from becoming senescent while maintaining their function.”

The paper is available online here.

Image (showing late-stage retinopathy, with pathological vessel growth) from Community Eye Health via Flickr.