Dietary restriction, or limited food intake without malnutrition, has beneficial effects on longevity in many species, including humans. A new study from the Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute (SBP), published today in PLoS Genetics, represents a major advance in understanding how dietary restriction leads to these advantages.

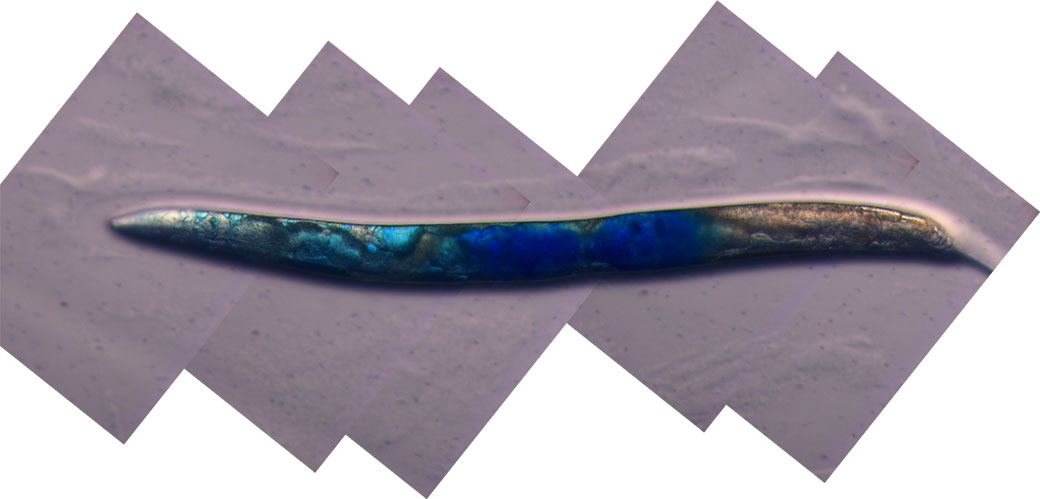

“In this study, we used the small roundworm C. elegans as a model to show that autophagy in the intestine is critical for lifespan extension,” said Malene Hansen, PhD, associate professor in SBP’s Development, Aging, and Regeneration Program and senior author of the study. “We found that the gut of dietary-restricted worms has a higher than normal rate of autophagy, which appears to improve fitness in multiple ways—preserving intestinal integrity and maintaining the animal’s ability to move around.”

Autophagy, or cellular recycling, is well known to play a role in lifespan extension. Autophagy involves breaking down the cell’s parts—its protein-making, power-generating, and transport systems—into small molecules. This both eliminates unnecessary or broken cell machinery and provides building blocks to make new cell components, which is especially important when starting materials are not provided by the diet.

In this study the research team wanted to understand how dietary restriction impacts autophagy in the intestine, whose proper function is already known to be important for long life.

“The strain of worms we used, called eat-2, is genetically predisposed to eat less, and they live longer than normal worms, so they provide an ideal model in which to investigate how dietary restriction extends lifespan,” said Sara Gelino, PhD, research associate in Hansen’s lab and lead author of the study. “We found that blocking autophagy in their intestines significantly shortened their lifespans, showing that autophagy in this organ is key for longevity.

“These results led us to examine how inhibiting autophagy impacts the function of the intestine. We found that while normal worms’ gut barriers become leaky as they get older, those of eat-2 worms remain intact. Preventing autophagy eliminated this benefit, which indicates that a non-leaky intestine is an important factor for long life.”

“How intestinal integrity relates to longevity is not clearly understood,” Hansen commented. “It’s possible that the decline in the gut’s barrier function associated with normal aging might let damaging substances or pathogens into the body.”

The research team also observed that turning off autophagy in the intestine made the slow-eating, long-lived worms move around less.

“The decrease in physical activity indicates that autophagy in one organ can have a major impact on other organs, in this case probably muscle or motor neurons,” said Hansen. “Finding the link between motility and autophagy in the intestine will require further research, but we speculate that inhibiting autophagy in the gut may impair the gut’s ability to metabolize nutrients or secrete hormones important for the function of other organs.”

While these results suggest that boosting autophagy in the gut is generally beneficial, Hansen cautions that further research is needed: “Before we can consider regulating autophagy to manage disease, we need to learn a lot more about how the process works both in a single cell as well as in the whole organism.”

Many of these future studies will also employ C. elegans. “Even though worms are much simpler than humans, many of the same basic mechanisms drive their biology. The knowledge we gain from this fast-paced research could eventually contribute to the development of new treatments that help people live longer, healthier lives,” added Hansen.

The paper is available online here.