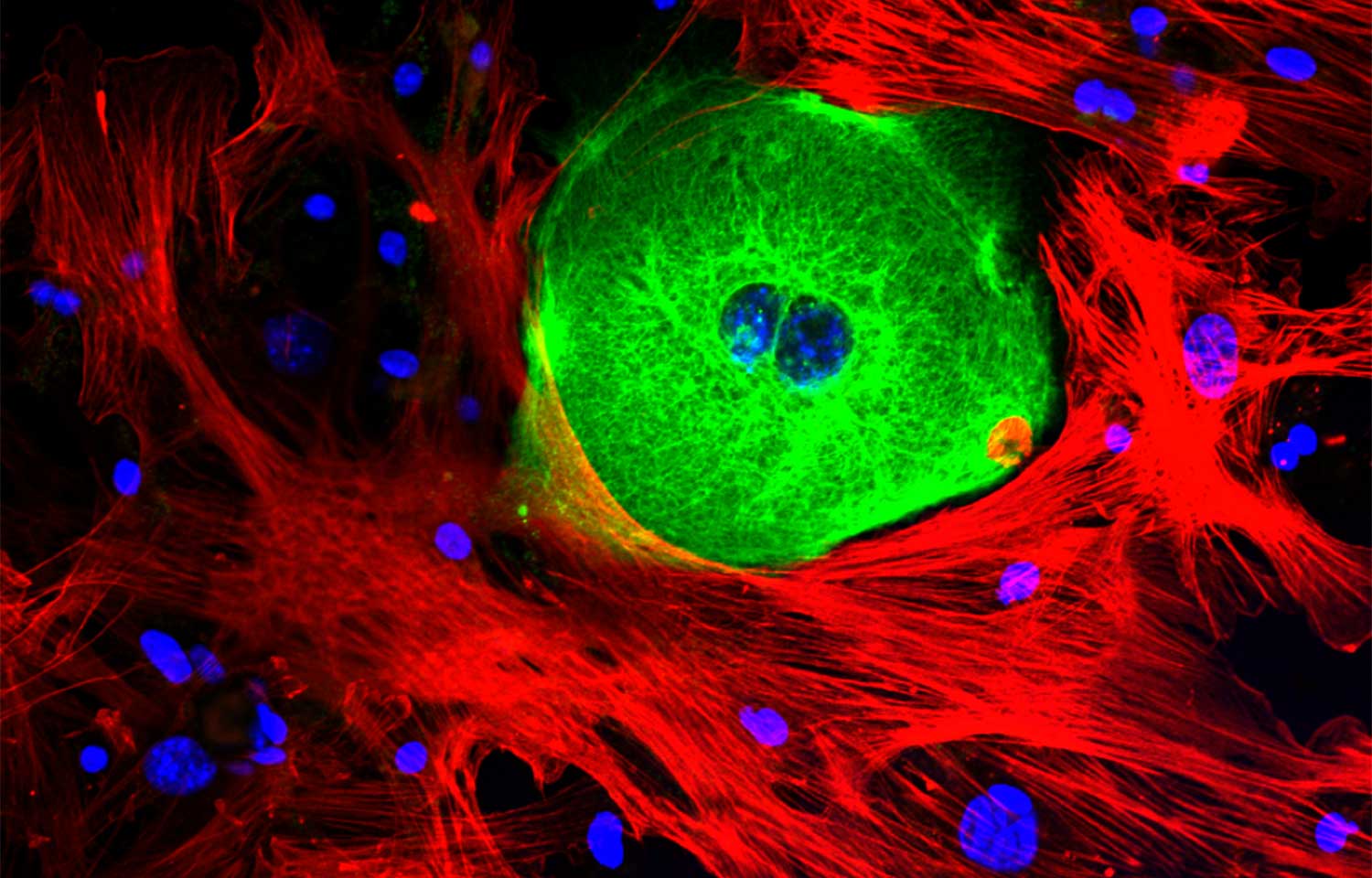

The image above is not only stunning, it’s also helping scientists uncover the secrets to cancer and additional diseases.

The technique that created this image—fluorescent microscopy—is so essential to biomedical research we asked Petrus R. de Jong, MD, PhD, research assistant professor at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute (SBP), to tell us a bit more about it. [Note: The image above shows a cancer cell, visualized as green, surrounded by structure-supporting stroma cells, visualized as red. DNA is shown in blue.]

What is fluorescent microscopy?

First, we must understand that light is a wave that has energy. If you’ve ever been hit by a wave at the beach, you’ve felt wave energy.

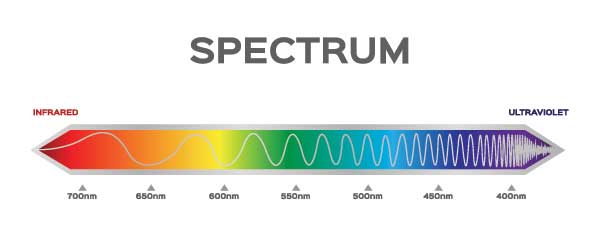

In addition to having energy, light has different speeds. Blue light has more energy than green light, and green light has more energy than red light. [See spectrum visual.]

We know all energy goes downhill—an overarching scientific principle. So if we shine high-energy blue light on a fluorescent molecule, lower-energy green light will appear.

Fluorescent microscopy harnesses this principle. The microscope beams light on the dyed sample, causing the fluorescent molecules to shine. Scientists then study the images.

Why would scientists use fluorescent microscopy for their work?

Using this technique, we can visualize life at all levels—from the single molecule dangling from a cell to our entire stomach. We can see if a drug is helping or hurting our body. We can watch how cancer cells interact with their environment. We can even track cancer cells that spread to other organs, a deadly process called metastasis. All this information helps scientists learn about who we are and how disease affects the body.

[Read more on how de Jong is using fluorescent microscopy in his research.]

Is fluorescent microscopy hard? How long would it take a scientist to make this kind of image?

The technique has gotten easier to use over time, but it still takes a while to optimize. Scientists have to be careful about the natural fluorescence of cells, called background fluorescence, which can affect results. The dyes can also interact with each other.

It usually takes us a couple of tries over a few weeks to optimize our process. After that, it’s about a day or so to obtain the images—not counting the time to prep our samples. Analysis of the images takes another few days.

Could you tell us more about the history of this technique? When was fluorescent microscopy invented?

The first documented observation of fluorescence involved a tree used by the Aztecs for medicinal purposes. When soaked, the bark made water glow bright blue. The tree is called “coatli” by Aztecs and is also known as “Mexican kidneywood.”

Many discoveries later, the first fluorescent microscopes were developed by German scientists Otto Heimstaedt and Heinrich Lehmann between 1911 and 1913. But there were two additional advances that really allowed the technology to take off.

In 1941, the fluorescent dye was attached to a targeted antibody. Instead of just measuring natural fluorescence levels of a sample, the dye could be directed to specific parts of a cell or organism. However, the dyes were still difficult to create and manipulate, limiting the technique’s use. It was a bit like assembling furniture—it can be done, but it’s not easy.

That changed twenty years later when a team of San Diego scientists discovered green fluorescent protein in jellyfish in 1962. This protein packages itself—like self-assembling furniture—which really enabled the technique to take off. Today, the technique is essential to biomedical research; nearly every scientist uses it to inform his or her research.

To learn more about fluorescence, check out the resources below.

Protein Data Bank Molecule of the Month: Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP)

The Fluorescence Foundation: A Short History of Fluorescence

Interested in keeping up with SBP’s latest discoveries, upcoming events and more? Subscribe to our monthly newsletter, Discoveries.