There has never been a more exciting time to embark on a career in biomedical research. Fortunately, the American Heart Association (AHA) is supporting early-career scientists with passion, commitment and focus by providing fellowships that fund their pursuit of cardiovascular research. Recently, three SBP scientists were awarded AHA grants to finance projects that align with the AHA mission of building healthier lives, free of cardiovascular disease and stroke.

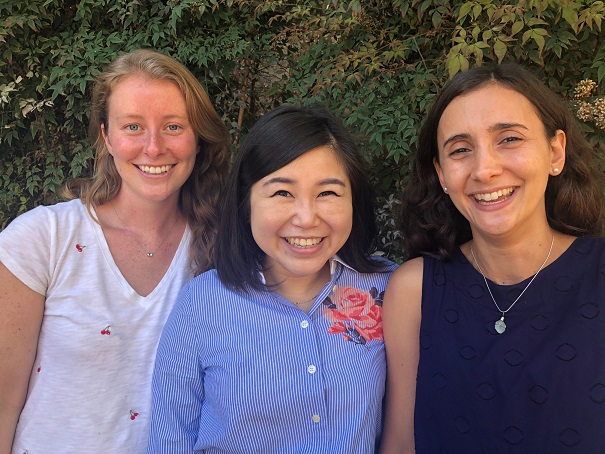

Katja Birker (left)

Birker, a graduate student in the lab of Rolf Bodmer, PhD, will be studying genes that could possibly contribute to hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS)—a condition that affects roughly 2–4 out of every 10,000 babies. Today, the cure for HLHS is a three-step invasive surgery that begins two weeks after the baby is born.

Birker will be collaborating with the Mayo Clinic to identify and test whether candidate HLHS genes found in patients have similar consequences in the hearts of fruit flies, which are an established model organism for cardiovascular research. She will use the flies to work toward her goal of validating novel genes that could be used in the future for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes related to cardiovascular diseases.

EePhie Tan, PhD (middle)

Tan’s research is taking a deeper dive into previous research showing that the cell recycling process called autophagy provides health benefits—including life extension—in response to reduced food intake. This project will examine the cell networks that govern autophagy, and a specialized form of autophagy called lipophagy (fat recycling). Lipophagy is a relatively new field of biomedical research, but scientists have already learned that malfunctions in lipophagy can lead to the accumulation of toxic fat deposits and contribute to heart disease.

Tan, a postdoc in the lab of Malene Hansen, PhD, will use a small worm called C. elegans as a model system to study proteins involved in the lipophagy process. Since the core machinery of lipophagy is conserved in all organisms (from humans to C. elegans), Tan’s findings may be used to find future treatments that target toxic fat deposits in heart disease.

Clara Guida, PhD (right)

Guida will study why children from obese parents have an increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease. The research may lead to the development of biomarkers that can predict heart conditions caused by parents that eat a high-fat diet (HFD), and may lead to new drugs that can prevent the negative effects of a parental HFD on the heart function of offspring.

Guida, a postdoc in Bodmer’s lab, will study the inheritance of DNA modifications called “epigenetic marks” in fruit flies fed a HFD. These epigenetic marks are thought to cause heart problems in the next generation. She will be testing potential drugs to see if they can erase the inherited abnormal gene changes and prevent the negative effects of a parental HFD. The research is especially relevant to lipotoxic cardiomyopathy—a condition associated with fat accumulation in the heart.