In their quest to treat cardiovascular disease, researchers and pharmaceutical companies have long been interested in developing new medicines that activate a heart protein called APJ. But researchers at Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute (Sanford-Burnham) and the Stanford University School of Medicine have now uncovered a second, previously unknown, function for APJ--it senses mechanical changes when the heart is in danger and sets the body on a course toward heart failure. This means that activating APJ could actually be harmful in some cases--potentially eye-opening information for some heart drug makers. The study appears July 18 in Nature.

"Just finding a molecule that activates APJ is not enough. What's important to heart failure is not if this receptor is 'on' or 'off,' but the way it's activated," said Pilar Ruiz-Lozano, PhD, who led the study. Ruiz-Lozano, formerly assistant professor at Sanford-Burnham, is now associate professor of pediatrics in the Stanford University School of Medicine and adjunct faculty member at Sanford-Burnham.

Stretching the heart

APJ is a receptor that sits on the cell surface in many organs, where it senses the external environment. When a hormone called apelin comes along and binds APJ, it sets off a molecular chain reaction that influences a number of cellular functions. Many previous studies have shown that apelin-APJ activity directs beneficial processes such as embryonic heart development, maintenance of normal blood pressure, and new blood vessel formation.

According to Ruiz-Lozano's latest study, however, APJ can also be activated a second, more harmful, way that doesn't involve apelin. In this pathway, APJ senses and responds to mechanical changes in the heart.

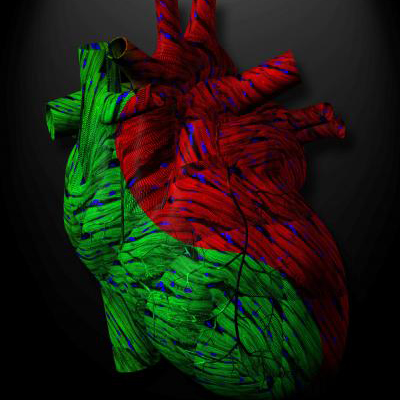

To better understand these mechanical changes, let's look at a person with high blood pressure. In this case, the person's heart has to work harder to pump the same amount of blood at the same rate as a healthy person. To meet the increased demand, individual heart muscle cells start making more proteins, making the cells bigger. Eventually, cell membranes stretch and each cell begins to pull away from its neighbor. This leads to an enlarged heart--a condition known as hypertrophy. In pathological (disease) conditions, hypertrophy can lead to heart failure.

APJ and heart failure

The best way to determine the role a protein plays in a particular cellular process is to see what happens when it's missing. To do this, Ruiz-Lozano's team, including co-first authors Maria Cecilia Scimia, PhD and Cecilia Hurtado, PhD, used mice that lack APJ. Under everyday conditions, the APJ-deficient mice appeared perfectly normal. However, unlike their normal counterparts, the mice lacking APJ couldn't sense danger when their hearts enlarged. As a result, mice were actually healthier without APJ--none succumbed to heart failure.

"In other words, without APJ, ignorance is bliss--the heart doesn't sense the danger and so it doesn't activate the hypertrophic pathways that lead to heart failure," Ruiz-Lozano said. "This tells us that, depending on how it's done, activating APJ might make matters worse for heart disease patients."