Addiction is perhaps the most and least visible of public health crises in the United States.

Tens of millions of Americans are addicted to illicit drugs, alcohol, tobacco and other substances including opioids, with both immediate and long-term harm to not just themselves, but also family, friends and society.

At the same time, many of those affected deny or hide their addictions. Most do not seek help. A 2021 national survey on drug use and health by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), for example, found that 94% of people aged 12 or older with a substance use disorder did not receive any treatment. Nearly all of them thought they did not require it.

The underlying psychology of denial is complicated, often involving behaviors to avoid adverse consequences and fear of stigma. There is another factor too: Treatments for addiction are myriad, but success is far from assured.

“Whatever the source of the addiction, the result is a chronic, relapsing brain disorder for which specific, approved treatments may be few, limited in their effectiveness and sometimes not broadly accessible,” says David Brenner, MD, president and CEO of Sanford Burnham Prebys.

“That’s why the work we do here is so important. Before you can truly treat something as complex as addiction, you need to deeply understand how it works. Substances such as alcohol and fentanyl may share underlying pathologies and yet, they are different.

“With that knowledge, you can begin to discover and test new therapeutic approaches capable of breaking the addiction cycle and restoring health.”

In recent months, researchers at Sanford Burnham Prebys have earned a series of federal grants and awards, totaling almost $25 million, to advance research—including clinical trials—that may turn the rising tide and toll of addiction.

Here’s a snapshot of addiction research at Sanford Burnham Prebys, where it’s at and where it’s going.

Tobacco

Smoking continues to be the leading cause of preventable deaths in the United States, and the second leading cause of preventable deaths worldwide after hypertension (of which smoking is a risk factor).

Smoking continues to be the leading cause of preventable deaths in the United States, and the second leading cause of preventable deaths worldwide after hypertension (of which smoking is a risk factor).

“Current Food and Drug Administration-approved therapies for nicotine addiction work less than 30% of the time,” says Nicholas Cosford, PhD, co-director and professor in the Cancer Molecular Therapeutics Program at Sanford Burnham Prebys’ Cancer Center. “Relapse is common after quitting. In any given year, 30% to 50% of U.S. smokers will attempt to quit, but the success rate is low, just 7.5%.”

Nicholas Cosford discusses the potential of a new, safe, effective way to quit smoking.

Cosford, in collaboration with colleagues at UC San Diego and Camino Pharma LLC, a San Diego-based biotechnology company he co-founded, has received a $9 million award from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) to advance an investigational drug called SBP-9330 to Phase 2 clinical trials.

“Our drug, SBP-9330, works through a different mechanism distinct from currently available medicines,” says Cosford. “It’s taken orally. It may give people who want to quit smoking a new, safe, effective way to kick the habit.”

Methods to treat nicotine addiction are quite limited. They include cognitive therapies and nicotine replacements such as transdermal patches and chewing gum. Only two drugs have been approved, bupropion and varenicline, but both drugs have significant side effects that lead to quit rates of approximately 20%.

Originally discovered by Cosford’s research team at Sanford Burnham Prebys, SBP-9330 targets a neuronal signaling pathway that underlies addictive behaviors, including tobacco use. If ultimately approved for market, it would be a first-in-class oral therapeutic to help people quit smoking.

The compound works by selectively targeting and reducing levels of glutamate, a master neurotransmitter vital to memory, cognition and mood regulation and specifically linked to addiction and relapse behavior.

In preclinical studies, SBP-9330 reduced nicotine self-administration in animal studies. In a Phase 1 clinical trial, the compound was found to be safe and well-tolerated in human.

“Our research suggests that SBP-9330’s mechanism of action—how it works—may also be effective for other types of addiction, such as cocaine, opioid and methamphetamine,” says Douglas Sheffler, PhD, co-principal investigator with Cosford and a research assistant professor at Sanford Burnham Prebys.

“In the future, we hope to explore and broaden the drug’s therapeutic uses.”

Disclosure: The development of SBP-9330 was supported by grants from NIH (Awards U01DA051077 and U01DA041731). Dr. Cosford has an equity interest in Camino Pharma, LLC, a company that may potentially benefit from the research results. Dr. Cosford’s relationship with Camino Pharma, LLC has been reviewed and approved by Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute in accordance with its conflict-of-interest policy.

Alcohol

More people consume alcohol in the U.S. than any other addictive substance: 133 million at last count. Almost half of them, according to the 2021 SAMHSA survey, are binge drinkers (five or more drinks on an occasion for men, four or more for women).

Alcohol addiction is dually reinforcing. It activates the brain’s reward system to produce feelings of pleasure, but also causes negative emotional states, such as anxiety and emotional pain. Alcohol addiction—and the diagnosis of alcohol use disorder—happens when consumption veers from drinking for pleasure to drinking motivated by attempts to reduce the emotional and physical discomfort of not drinking.

Sheffler is principal investigator and Cosford co-investigator on a $4 million award from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) to support the advancement of small molecule compounds targeting the corticotrophin-releasing factor (CRF) system in the brain.

Doug Sheffler discusses how we might treat multiple symptoms that contribute to alcohol dependence.

CRF is a hormone regulated by two proteins, designated CRF1 and CRF2, that produce a wide range of physiological responses to stress, from appetite suppression and increased anxiety to improved memory and selective attention.

Sheffler, Cosford and colleagues have developed small molecule compounds that can inhibit the interaction between CRFs and CRF-binding proteins, effectively dampening the stress connection and its promotion of alcohol addiction. The new funding will further animal studies to validate their approach.

With a different $1.97 million NIAAA grant, Sheffer as principal investigator and Cosford as co-investigator will take a page from their smoking research to explore whether compounds called positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) can be used to target the same glutamate neurotransmitters involved in other types of addiction.

“We think this approach might effectively treat multiple symptoms that contribute to alcohol dependence and relapse, including reduced responsiveness to other drug cues, physical withdrawal symptoms and sleep disturbances,” says Sheffler. “The goal is to assess whether these PAMs represent a new pharmacological treatment for alcohol use disorder.”

Opioids

No addiction epidemic garners more headlines or greater notoriety than drug abuse, specifically the dramatic rise in overdose deaths fueled by synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, a powerful analgesic typically used to treat patients with severe pain, especially after surgery. Fentanyl is similar to morphine but 50 to 100 times more potent.

In 2021, fentanyl and other synthetic opioids accounted for nearly 71,000 of 107,000 fatal drug overdoses in the U.S. By comparison, in 1999 drug-involved overdose deaths totaled less than 20,000 among all ages and genders.

Like other addictive substances, opioids are intimately related to the brain’s dopamine-based reward system. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that serves critical roles in memory, movement, mood and attention. High or low dopamine levels are associated with conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and restless leg syndrome.

But dopamine is perhaps best known for its role in the brain’s reward system where it acts as the “feel-good” hormone. Our brains are hard-wired to seek out behaviors that release dopamine, which is why junk food and sugar can be addictive. The more you eat them, the greater the dopamine release.

The same principle applies to opioid use, only with stronger and more dire effects.

For several years, Michael Jackson, PhD senior vice president of drug discovery and development at Sanford Burnham Prebys’ Conrad Prebys Center for Chemical Genomics and co-principal investigator Lawrence Barak, MD, PhD at Duke University, have been developing a completely new class of drugs that works by targeting a receptor on neuron called neurotensin 1 receptor or NTSR1, that regulates dopamine release.

The researchers recently received a $6.3 million award from NIH and NIDA to advance their addiction drug candidate, called SBI-810, to the clinic.

Michael Jackson discusses the potential of a truly new, first-in-class treatment for addiction.

Earlier studies found no easy way to affect NTSR1 function without causing significant adverse side effects. In 2019, Sanford Burnham Prebys researchers, in collaboration with Barak and Lauren M. Slosky, PhD at Duke University, described encouraging results with a drug candidate they discovered called SBI-533. The compound modulates NTSR1 signaling and shows robust efficacy in mouse models of addiction with no adverse side effects.

SBI-810 is an improved version of SBI-533. Both are small molecules that can be taken orally and readily cross the blood-brain barrier to reach NTR1 receptors. The new funding will be used to complete preclinical studies and initiate a Phase 1 clinical trial to evaluate safety in humans.

“The novel mechanism of action and broad efficacy of SBI-810 in preclinical models hold the promise of a truly new, first-in-class treatment for patients affected by addictive behaviors,” says Jackson.

Jackson and colleagues also have a $2.15 million grant from the NIH and NIDA to develop a novel, brain-penetrating small molecule that modulates the function of another brain receptor, GPR88. GPR88 is an orphan G-protein coupled receptor that, in mouse studies, was found to inhibit opioid receptor signaling. The goal is to develop a drug that binds GPR88 and diminishes addiction-relevant behavioral responses to opioid drugs and lessens the anguish of withdrawal.

“This is a new drug target in a field that needs as many new, viable targets as we can find,” says Jackson. “Given preclinical observations, we want to leverage our expertise at the Prebys Center to formally validate whether GPR88 is a high-potential target and, if so, pursue it as a new therapy for long-term abstinence from opioid use.”

The Biology of Addiction

By definition, people with addictions lose control over their actions, whether it’s tobacco, alcohol, drugs or other substances. They crave and seek them regardless of adverse consequences and struggle or fail when trying to quit.

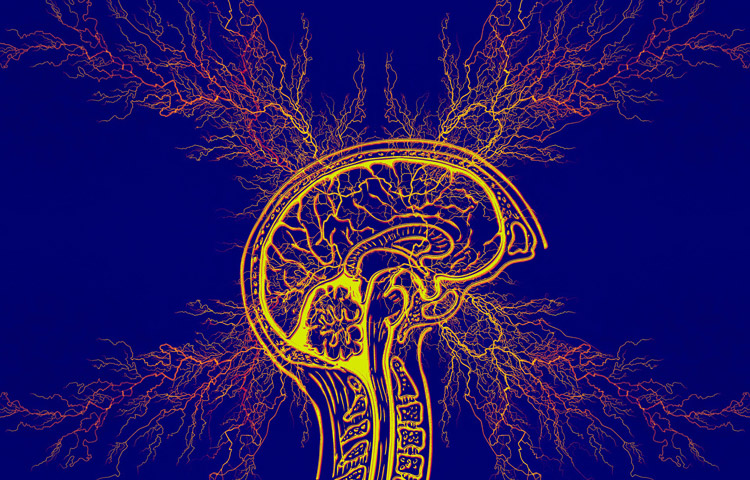

Much of the power of addiction lies in its ability to hijack, circumvent or even destroy key parts of the brain that would moderate or block addictive behaviors. Fundamentally, this involves the addictive substance subverting neural regions normally involved in rewarding healthy behaviors, such as exercising or bonding with loved ones.

Instead, addictive substances hijack these pleasure/reward circuits to promote ever-greater consumption, and may trigger other circuits that boost adverse feelings of anxiety, stress or paranoia.

Repeated use can damage the essential decision-making region in the front of the brain, reducing the conscious ability to recognize the harms of addictive substances.

Substance abuse spans addictions, from tobacco to alcohol to illicit drugs.

Tobacco

Commercial cigarette smoking among U.S. adults has declined over the past 50 years. Nonetheless, an estimated 46 million U.S. adults use tobacco products, including cigarettes, e-cigarettes, cigars, smokeless tobacco and pipes.

Tobacco is indisputably harmful to health. It is the leading cause of preventable disease and death, accounting for more than 480,000 deaths every year in the United States, or about 1 in 5 deaths.

Cigarette smoking is responsible for approximately 90% of lung cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease cases. It is cause or risk factor for many other cancers. Tobacco use is strongly linked to heart disease, stroke, asthma, diabetes, adverse reproductive effects in women, premature and low birth-weight babies and age-related macular degeneration.

Nicotine, the chief active constituent in tobacco, is highly addictive. For regular cigarette smokers, addiction is almost inevitable. Even for light smokers—those who smoke one to four cigarettes per day or fewer—a 2020 study found they met the criteria for nicotine addiction.

Quitting smoking is difficult. Roughly seven in 10 adult cigarette smokers surveyed say they want to stop; and more than half of smokers attempt to quit each year. The success rate is less than 8%. Similar numbers apply to youth tobacco users.

Alcohol

According to the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 219.2 million Americans ages 12 and older say they have consumed alcohol at some point in their lives; 133 million are current alcohol users and 60 million are binge drinkers. Almost 85 percent of Americans age 18 (the lowest legal drinking age in some states) and older report having done so, but one in five youths between ages 12 and 17 also report drinking alcohol.

Addiction to alcohol can manifest physiologically, psychologically or both. Alcohol Use Disorder (colloquially known as alcoholism) describes an inability to control drinking. In 2021, almost 30 million Americans ages 21 and older suffered from AUD, including 894,000 U.S. adolescents ages 12 to 17.

Alcohol is a primary cause of liver disease and related deaths: more than 100,530 in 2021 alone. One in three liver transplants is due to alcohol-associated liver disease; and 4 percent of all cancer deaths are attributable to alcohol consumption.

Alcohol abuse and addiction carry broad and calamitous consequences for society. More than 10 percent of U.S. children ages 17 and younger liver with a parent who has AUD. Alcohol plays a role in more than 7% of emergency department visits, and is linked to more than 140,000 deaths annually, making alcohol the fourth-leading preventable cause of death in the U.S. after tobacco, poor diet and physical activity and illegal drugs.

Drugs

Drug overdose deaths nationwide are rising, most sharply in recent years, according to data compiled by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. In 1999, for example, drug-involved overdose deaths totaled under 20,000 among all ages and genders. In 2021, the figure was 106,699.

Synthetic opioids (mostly fentanyl) were the primary scourge, accounting for nearly 71,000 fatal overdoses reported in 2021. Stimulants including cocaine and methamphetamine, accounted for more than 32,500 deaths in 2021.

In 2021, more than 60 million persons in the U.S. age 12 and older had used illicit drugs in the past year, most commonly marijuana. Nearly 10 million had misused opioids. Twenty-four million persons met the criteria for having a drug use disorder; almost all (94%) of whom received no treatment.

Drug abuse and addiction is strongly linked to mental health, with nearly one in three adults reporting either a substance use disorder or mental illness, such as major depression or suicide ideation.