Every 34 seconds, someone in the US has a heart attack or stroke. New research from the laboratory of Erkki Ruoslahti, MD, PhD, distinguished professor in the NCI-designated Cancer Center, could lead to treatments that lower that frequency.

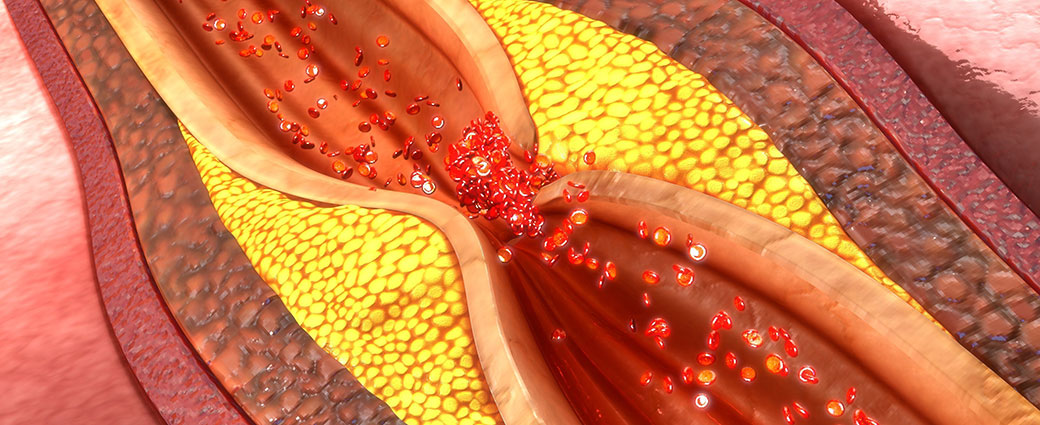

Heart attacks and strokes are caused by a blocked artery, which cuts off blood supply to a part of the heart or brain. These blockages occur when atherosclerotic plaques—deposits of inflamed, fat-containing cells surrounded by fibrous material inside arteries—rupture and seed blood clots. In a study published in the Journal of Controlled Release, Ruoslahti’s team shows that a specific peptide blocks expansion of these plaques at advanced stages.

“Our findings demonstrate the relevance of a new target, p32, to slowing the deposition of plaque,” said Zhi-Gang She, PhD, staff scientist in Ruoslahti’s lab and co-lead author of the paper. “We’re hopeful that drugs that act on this protein would help lower the risk for heart attacks and stroke.”

The details

The new study used a peptide called LyP-1, a ring of nine amino acids that Ruoslahti’s group has worked with for many years. LyP-1 binds to p32, a protein that’s normally located inside cells, but is found on the surface of tumor cells and active macrophages.

“Macrophages drive plaque enlargement by taking up fats and promoting inflammation, and we knew from our other investigations that LyP-1 can trigger cell death in macrophages,” explained Ruoslahti. “We thought that LyP-1 might eliminate macrophages from plaques, which would slow the advance of atherosclerosis.”

Their results confirmed this expectation—the LyP-1 peptide greatly reduced the size of plaques in mice when it was administered at advanced stages.

“Eliminating macrophages from arterial plaque is like cutting off the roots of a plant,” said She. “Not only does that get rid of a portion of the plaque, but because macrophages feed it by taking up lipids, it also keeps the plaque from getting larger.”

Clinical relevance

“The peptide itself is not a candidate drug,” added Ruoslahti. “It can only be given by injection, which isn’t practical for a chronic disease like atherosclerosis. However, we have identified small molecules that interact with p32 in a similar way to LyP-1, so they could form the basis of a drug that’s taken as a pill.”

“The key to making sure this treatment strategy is safe is confirming that it doesn’t make the plaques more likely to rupture,” commented She. “We didn’t see anything indicating that LyP-1 makes plaques less stable, but future studies should explore that issue further.”

The paper is available online here.