After a bone marrow transplant, it can take months for the number of T cells to reach healthy levels. Because T cells are crucial for launching an effective immune response, this leaves patients—usually cancer survivors whose immune systems were knocked out by chemotherapy—vulnerable to infections for longer. However, new research, to which Carl Ware, PhD, professor and director of the Infectious and Inflammatory Disease Center, contributed, identifies a novel target for immunotherapeutics to shorten this recovery time.

“This study shows that the lymphotoxin β receptor controls the entry of T cell progenitors into the thymus, the organ where T cells mature,” said Ware. “Future compounds that activate this receptor may help transplants give rise to functional T cells faster.”

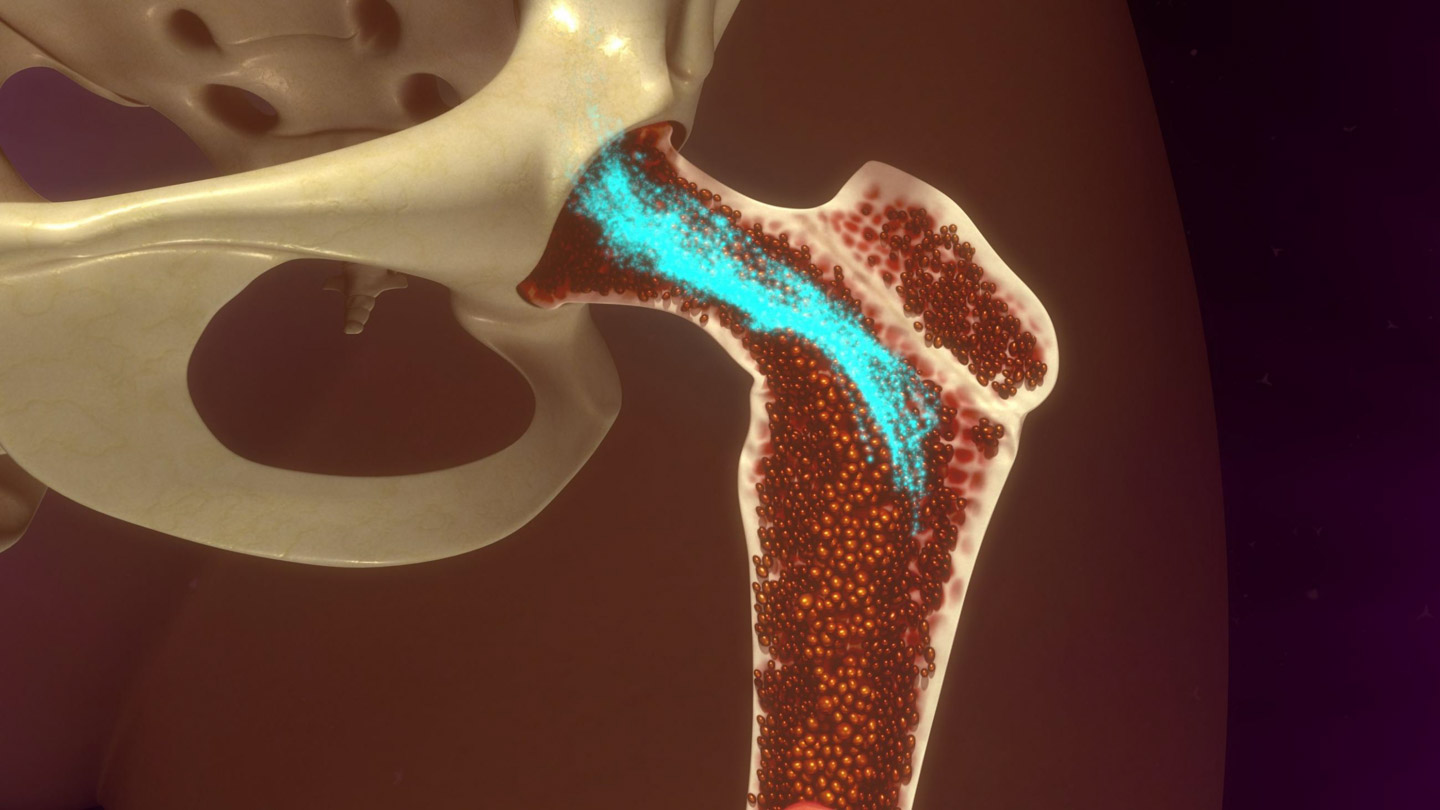

Within the overall immune response against invading bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens, T cells are the field officers and special forces. Helper T cells send chemical signals to get other parts of the immune system involved, and cytotoxic T cells recognize and kill infected cells directly. They’re ‘trained’ to distinguish threats from the cells of the body in the thymus, where T cell progenitors that react to normal, uninfected cells are eliminated.

Publishing in the Journal of Immunology, the team, led by William Jenkinson, PhD, and Graham Anderson, PhD, of the University of Birmingham, looked at the importance of various receptors in letting T cell progenitors into the thymus, and found that only the lymphotoxin β receptor was required.

Significantly, the researchers also showed that stimulating the lymphotoxin β receptor boosted the number of transplant-derived T cells.

“Post-transplantation, T cell progenitors can struggle to enter the thymus, as if the doorway to the thymus is closed,” said Anderson. “Our work points to a way to ‘prop open’ the door and allow these cells to enter and mature.”

Ware and his lab have made many contributions to understanding how the lymphotoxin β receptor, as well as other related receptors, affect immunity and inflammation.

“The lymphotoxin β receptor is important not only in the thymus, but also at sites of inflammation and infection,” Ware added. “Further investigation of the effects of activating it throughout the body will determine whether this treatment approach is feasible, or perhaps should be targeted to the thymus.”

The paper is available online here.