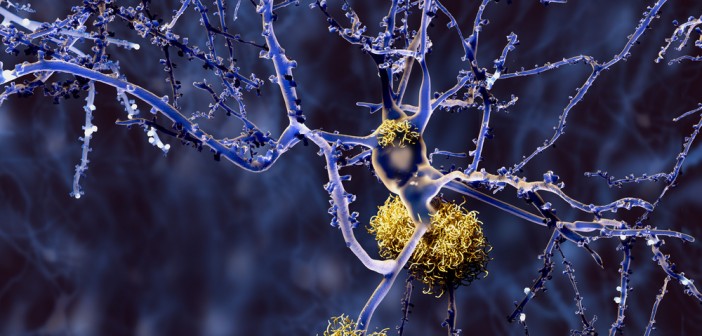

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), a common disorder that slowly destroys patients’ memory, is a highly complex disease. The condition arises when neuronal connections are lost following the accumulation of clumps of the protein beta-amyloid (called plaques) and the failure of mitochondria—the power plants within cells. Because there are many pathways that can contribute to both processes, understanding how AD progresses in all patients requires synthesizing the results of many research studies.

Researchers in the lab of Huaxi Xu, PhD, professor at SBP, are on a mission to help complete the AD puzzle. In their recent study published in Scientific Reports, the team showed that humans with AD have decreased levels of the mRNA that codes for a protein called RPS23RG1, and that by increasing levels of the protein in mouse models of AD they can improve spatial learning and preserve neural connections.

“We are excited to have discovered this new contributor to Alzheimer’s pathogenesis. Our new results strongly suggest that increasing levels of RPS23RG1 may be a potential therapeutic approach for treating AD,” said Xu.

“Although little is known about the normal function of RPS23RG1, we previously published a study in Neuron (2009) showing that in mice, it regulates beta-amyloid levels and tau phosphorylation. Tau phosphorylation is a process that leads to neurofibrillary tangles, another significant pathology found in AD.”

“Our next step is to continue to examine how RPS23RG1 levels may be increased to treat AD and learn more about the general role of the protein in normal healthy brains.”

To read the paper click here.