Three years ago, Alexey Terskikh, PhD, associate professor in Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute’s (SBP’s) Development, Aging and Regeneration Program, published a groundbreaking study showing that stem cells could be used to grow hair.

This discovery could help more than 80 million men, women and children in the United States experiencing hair loss. Across cultures, personal identity is connected with hair. As a result, hair loss often affects emotional well-being and self-esteem. There is clear interest in the technology: Our 2015 story on this finding remains our blog’s most-read article.

Since then, Terskikh and his team have been working hard to advance this technology. We caught up with Terskikh to learn about his progress—and how far away the research remains from human studies.

Could you fill us in on your work since 2015?

For the past three years, my team and I have been working to overcome several obstacles to the technology’s real-world use. We’ve made progress on multiple fronts, summarized below:

Generating unlimited cells

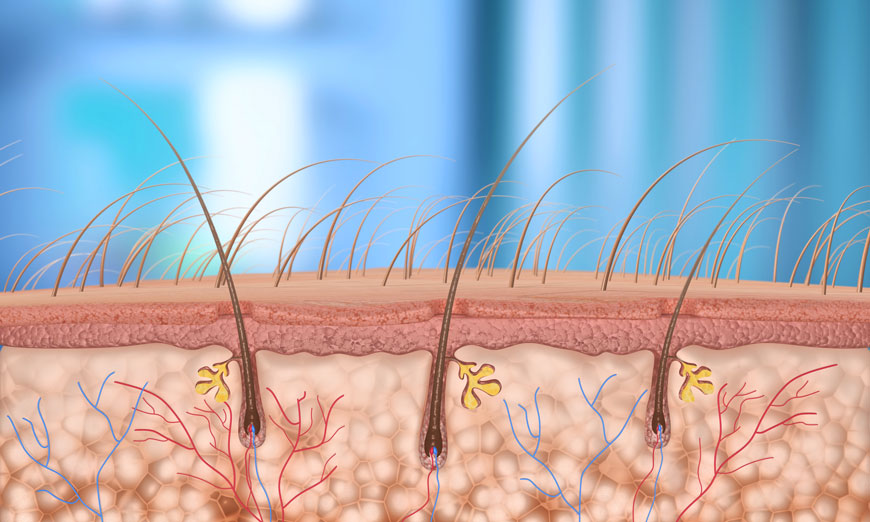

Instead of embryonic stem cells, which are difficult to obtain, our method now uses induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC), which are derived from a simple blood draw or skin sample. iPSCs allow us to create an unlimited supply of cells to grow hair. Not having enough hair is one reason current transplants don’t work, so this is a critical advance.

Creating a natural look

Hair actually grows in a specific direction, so it’s important to control the orientation of hair growth to achieve a natural look. Your hair stylist is familiar with this!

We’ve found a solution—3D biodegradable scaffolds—and partnered with leading scientists in the field to advance our project. The scaffold allows us to control the number of cells transplanted, their direction and where they are placed.

Helping the transplant “take”

The scaffold has a second job of helping seed hair follicles. Skin is a good barrier—that’s its job—so we needed something to help the transplant “take.” The scaffold provides the “soil” from which the hair can grow.

generated from iPSC present within hair

follicles grown in mouse skin.

I understand you have formed a company based on this research. Can you tell us more?

Yes, we have formed a company this year and assembled a great team with the expertise needed to move the technology forward. These experts include hair transplantation specialists, experienced entrepreneurs and experts in manufacturing cells at large scale (not a trivial endeavor).

While hair loss affects people’s self-esteem and self-image, it isn’t life threatening, so it’s not a top priority for many funding agencies. Forming a company gives us a vehicle for raising capital to advance this technology.

Do you know how the stem cell–generated hair will look? Can you control hair color?

We hope that stem cell–generated hair will look exactly as the original hairs that have been lost. Of course, it will take some time to grow a “perfect” hair, but we believe this should be possible in the long run.

Has anything surprised you during this process?

I expected to hear from young and older men, but I was surprised by the number of women who reached out to express interest in our research. I received about an equal number of emails from women. Pregnancy, menopause and ovarian conditions may all cause hair loss for women.

Most heartbreaking were emails from parents of children with alopecia, a condition where a child cannot grow hair. As you can imagine, hair loss at such a young age can affect relationship formation and self-image. All these emails continue to motivate me to keep advancing this research as quickly as possible.

What work needs to be done before you can test this on humans? How far away are we from this product being used on humans?

The good news is that we’ve resolved the biological mystery of hair growth using stem cells. Now, it is mostly an engineering exercise: how to get robust and properly oriented hair growth.

Before we can discuss human studies with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), we need to complete safety and tumorigenicity tests in mice. We are performing these tests very soon.

Provided we have the proper funding, we expect it will take two years before we can start discussions with the FDA.

Assuming all goes as planned and the FDA approves a first-in-human study, will everyone be eligible for the trial?

At that point we will work very closely with clinical experts in the field to determine which individuals are most likely to benefit from this research and should be involved in the trial.

How did you first get started on this research?

That’s actually a funny story. My father—who is a scientist—wanted to stay more in touch, so we decided to do a joint project. I was researching stem cells, and he was researching skin follicles, so we ended up here! If you look at the paper, you’ll see two authors who have the same last name—him and me.

Interested in keeping up with SBP’s latest discoveries, upcoming events and more? Subscribe to our monthly newsletter, Discoveries.