“Excellent presentation!”

“We should connect—we have more samples coming soon.”

“Feel free to reach out, we’re looking to partner so I’d love to hear more about your research.”

These exchanges, overheard at the 3rd annual La Jolla Aging Meeting held on March 29, 2019, at the Salk Institute, illustrate the importance of uniting scientists focused on a common goal: In this case, uncovering the root causes of aging.

As in previous years, the 2019 meeting was co-organized by Sanford Burnham Prebys’ Malene Hansen, PhD, and Peter Adams, PhD; and Salk’s Jan Karlseder, PhD A key goal of the event is to feature research by local scientists studying the molecular mechanisms of aging, while fostering connections and building relationships that advance new discoveries. More than 200 researchers, primarily from the San Diego area, attended the meeting.

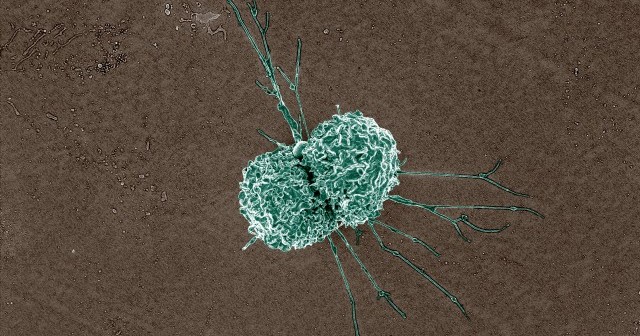

Aging is the main risk factor for many of the serious diseases our society faces today, including cancer, heart disease and Alzheimer’s. As the U.S. population grows older due to the natural aging of the Baby-Boomer generation, the need to understand the underlying causes of aging becomes more urgent. The number of Americans who are age 65 or older is projected to double from nearly 48 million in 2015 to more than 90 million in 2060, according to the United States Census Bureau.

The diversity of presentations given—from the role of supportive brain cells called astrocytes and cellular recycling (autophagy) to long-lived proteins in mitochondria (the cell’s power generator)—reflects the complexity of the field. A poster session was also held during the symposium, providing an opportunity for up-and-coming scientists to share their recent data.

For scientists new to the area, the meeting provided a key opportunity to build relationships.

“It’s unlikely there will be any single factor responsible for aging,” says Matt Kaeberlein, PhD, professor at the University of Washington and the symposium’s keynote speaker. “I am encouraged to see so many people interested in diverse aspects of aging biology at this symposium. By advancing each of these distinct research areas, and working together, we will make progress in understanding the underlying aging process.”

The full list of speakers follows. Make sure to save the date for next year’s meeting, which will be held on March 27, 2020.

- Matt Kaeberlein, PhD, University of Washington (keynote) – New insights into mechanisms by which mTOR modulates metabolism, mitochondrial disease and aging

- Isabel Salas, PhD, Allen lab, Salk – Astrocytes in aging and Alzheimer’s disease

- David Sala Cano, PhD, Sacco lab, Sanford Burnham Prebys – The Stat3-Fam3a axis regulates skeletal muscle regenerative potential

- Tina Wang, Ideker lab, University of California, San Diego – A conserved epigenetic progression aligns dog and human age

- Rigo Cintron-Colon, Conti lab, Scripps Research – Identifying the molecules that regulate temperature during calorie restriction

- Nan Hao, PhD, University of California, San Diego – Programmed fate bifurcation during cellular aging

- Shefali Krishna, PhD, Hetzer lab, Salk – Long-lived proteins in the mitochondria and their role in aging

- Sal Loguercio, PhD, Balch lab, Scripps Research – Tracking aging with spatial profiling

- Alva Sainz, Shadel lab, Salk – Cytoplasmic mtDNA-mediated inflammatory signaling in cellular aging

- Anthony Molina, PhD, University of California, San Diego – Mitochondrial bioenergetics and healthy aging: Advancing precision healthcare for older adults

- Alice Chen, Cravatt lab, Scripps Research – Pharmacological convergence reveals a lipid pathway that regulates C. elegans lifespan

- Robert Radford, PhD, Karlseder lab, Salk – TIN2: Communicating telomere status to mitochondria in aging

- Jose Nieto-Torres, PhD, Hansen lab, Sanford Burnham Prebys – Regulating cellular recycling: role of LC3B phosphorylation in vesicle transport

Prizes for the best poster presentations were awarded to the following scientists:

- Hsin-Kai Liao, PhD, Juan Carlos Izpisua Belmonte’s lab, Salk

- Yongzhi Yang, PhD, Malene Hansen’s lab, Sanford Burnham Prebys

- Tai Chalamarit, Sandra Encalada’s lab, Scripps Research

Thank you to our generous sponsor, the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research, and to NanoString for donating the prizes received by the poster presenters.

Interested in keeping up with our latest discoveries, upcoming events and more? Subscribe to our monthly newsletter, Discoveries.