Ruth Claire Black wasn’t entirely surprised when she was diagnosed with breast cancer six and a half years ago. Her mother had died at age 52 of breast cancer, only two years after she was first diagnosed, Black explained at our recent Fleet Science Center event. New treatments have allowed Black’s story to differ from her mother’s—but as breast cancer experts from Sanford Burnham Prebys and UC San Diego Health explained, there is still a long way to go.

“There is a great misconception that breast cancer is extremely easy to treat and is always cured. But the truth is that one in three women with early-stage breast cancer will relapse and eventually die from the disease,” said speaker Rebecca Shatsky, MD, a breast cancer oncologist at UC San Diego Health. “We are learning there aren’t one or two kinds of breast cancer—there are up to 30 different subtypes. To cure breast cancer, we need to look at treatments through a personalized lens.”

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer in American women. One in eight women will be diagnosed with breast cancer in her lifetime, and more than 40,000 women die each year from the cancer. Targeted treatments—such as those that block the HER2 receptor—and hormone-based therapies have extended survival. However, 30% of people with estrogen-positive breast cancer, the most common form, eventually stop responding to standard-of-care treatments, for reasons that are largely unknown.

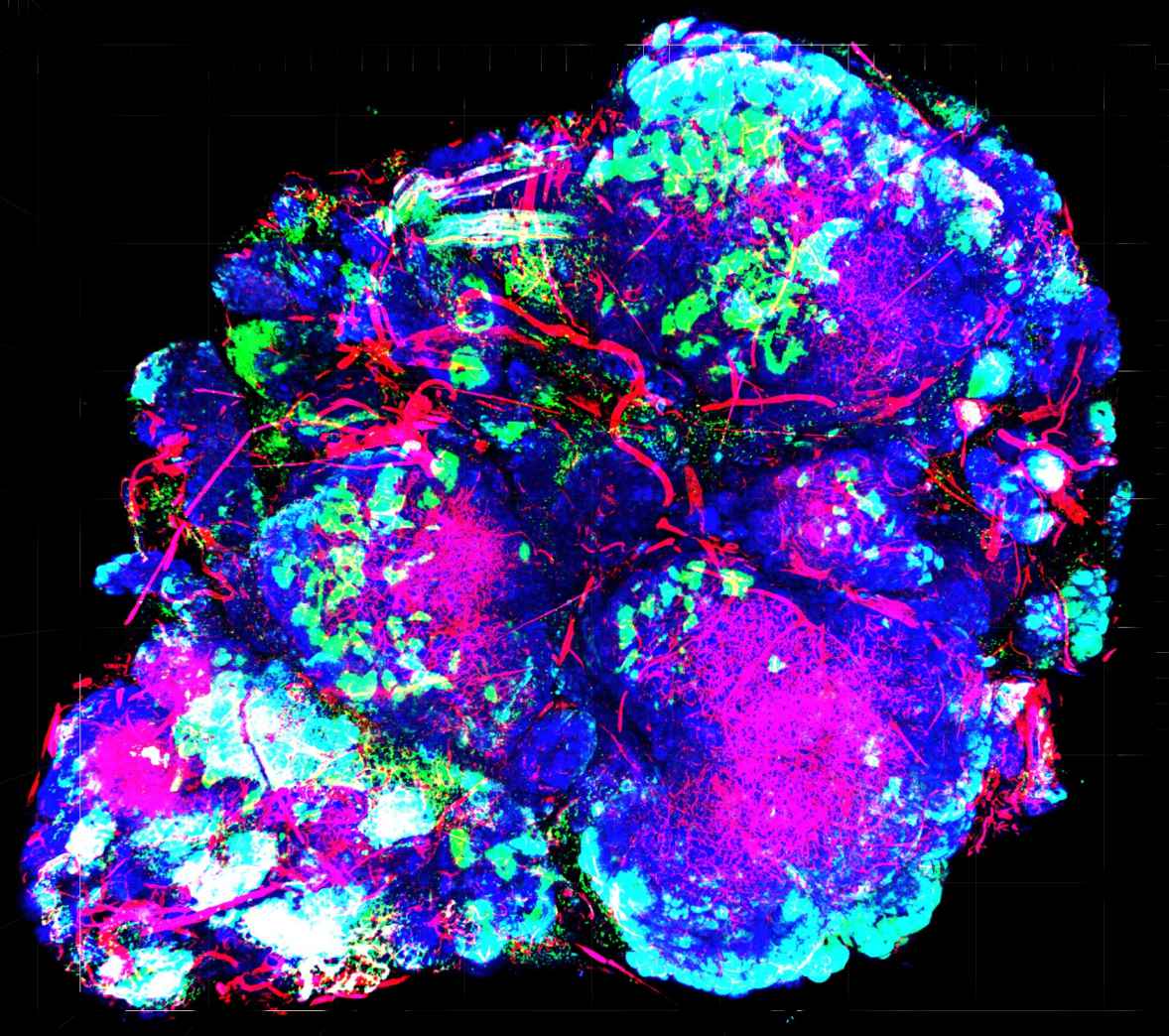

Speaker Svasti Haricharan, PhD, assistant professor at Sanford Burnham Prebys, is working to change these realities. Her work centers on a breast cancer subtype caused by defects in DNA repair machinery—a genomic “spell check” that normally corrects DNA copy errors during cell division. Nearly 20% of people who do not respond to breast cancer treatment have mutations in this machinery. Working with Shatsky, Haricharan’s team identifies breast cancer samples that have DNA damage repair defects. Then she tests these samples against thousands of FDA-approved treatments—with the goal of finding an effective treatment.

For people like Black, these advances can’t come soon enough.

“We have so much information about breast cancer. We have great diagnostics. Because of these tests, I know I’m a carrier of the BRCA2 mutation. I also know that it’s only a matter of time until my cancer returns,” said Black, who is a member of Sanford Burnham Prebys’ Community Advisory Board. “But doctors don’t know what to do with all of this information. That’s why I’m so supportive of the work taking place at Sanford Burnham Prebys. They are taking this information and doing something with it.”

This event was the third of our five-part “Cornering Cancer” series. Register today to join us for discussions on pancreatic cancer in November and pediatric brain cancer in December.