There may be a type 1 diabetes treatment one day that doesn’t involve injections, or a bulky external device, or even a transplant. Fred Levine, MD, PhD, professor and director of the Sanford Children’s Health Research Center, and his lab have discovered how the body regenerates beta cells, the cells that produce insulin. Future drugs acting by the same mechanism could eliminate—or greatly reduce—patients’ need for additional therapies to regulate their blood sugar.

Publishing in Cell Death and Disease, the team shows that using a drug to switch on a specific receptor causes certain cells in the pancreas to transform into the type that secretes insulin.

“The receptor we identified, protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2), is a very promising drug target,” said Levine. “Although this study was done in mice, we found evidence for the same phenomenon in humans. Thus, we think drugs that activate PAR2 would free diabetic patients of their reliance on insulin for as long as those beta cells survive.”

In type 1 diabetes, beta cells are destroyed by the immune system. Without insulin, the rest of the body’s cells don’t take up glucose after a meal, so glucose levels in the bloodstream can become extremely high. If it’s not treated, that excess blood sugar can cause life-threatening dehydration and coma. Even when diabetes is managed, repeated episodes of high blood sugar cause long-term organ damage. For example, diabetes is the leading cause of kidney failure.

“For type 1 diabetics, keeping their blood sugar in a healthy range takes a lot of vigilance, and can be pretty restricting,” explained Levine. “Plus, even the most careful planning and prompt insulin injections can’t regulate blood sugar as well as beta cells can. Our goal is to regenerate those cells.”

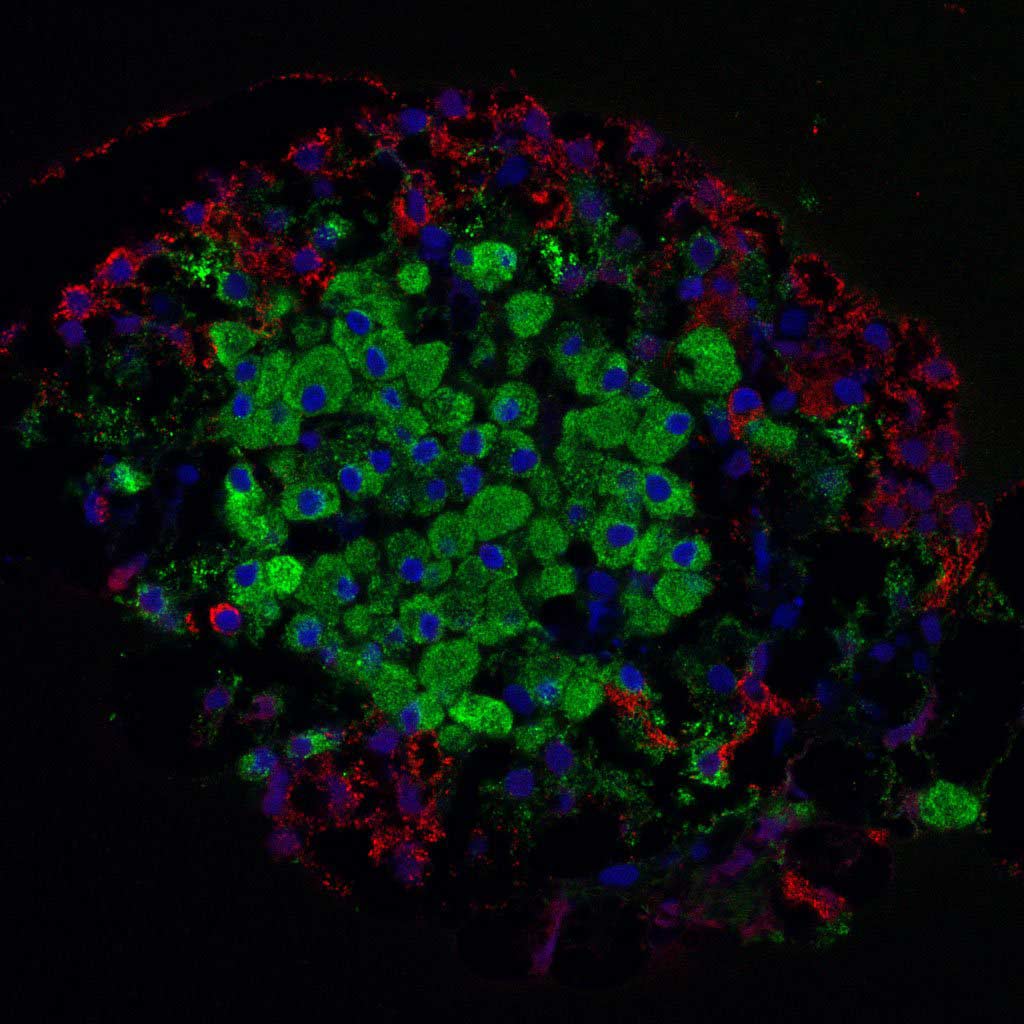

Scientists have been looking for ways to replace beta cells for decades. Whereas many others are working towards stem cell-based therapies, Levine’s group has instead focused on how the pancreas itself might make up for the lost cells. This began with an observation that injuring the pancreas of diabetic mice causes their alpha cells—which produce another blood sugar-regulating hormone called glucagon—to convert into beta cells. This so-called ‘transdifferentiation’ happens only if the insulin-making cells are absent, as they are in type 1 diabetes.

Levine and his research unit hypothesized that something released from the damaged pancreas tissue triggered the cell type switch—likely a digestive enzyme. The best candidate for how the enzyme ‘talks to’ alpha cells was via the signaling receptor PAR2, which can be activated by trypsin, a digestive enzyme. Indeed, the new study’s battery of experiments revealed that activating PAR2 spurs alpha cells to morph into beta cells.

PAR2 activators such as 2fLI, the one used by the Levine group, are already under investigation by the pharmaceutical industry to treat pain and inflammation, which could speed the application of the scientists’ new findings.

“We are hopeful that PAR2 activators such as 2fLI will be developed as a drug,” Levine commented. “It will take some effort, though, to find a way to get enough of it into the pancreas to induce replacement of a large number of beta cells. Current activators are eliminated from the circulation very rapidly, so we will likely need compounds with better pharmacokinetics.”

Because PAR2 is found in many other tissues, the investigators examined its role in other types of tissue repair. They found that the receptor is also crucial for replacing damaged tissue in the liver and regenerating the tips of fingers and toes.

“This discovery opens up a whole new area for us,” said Levine. “PAR2 appears to be a general regulator of regeneration. We plan to examine its role in a number of other tissues, and to explore the signaling that happens within the cell after it’s activated. That could lead to new drug targets not just for diabetes, but possibly other conditions as well.”