If your grocery store was out of food, would you still invite your friends to a dinner party?

Unless you happen to have a flourishing garden, probably not.

Our cells would have the same answer. Food is hard to come by, so cells in our body rarely share nutrients. The only product a cell releases is waste.

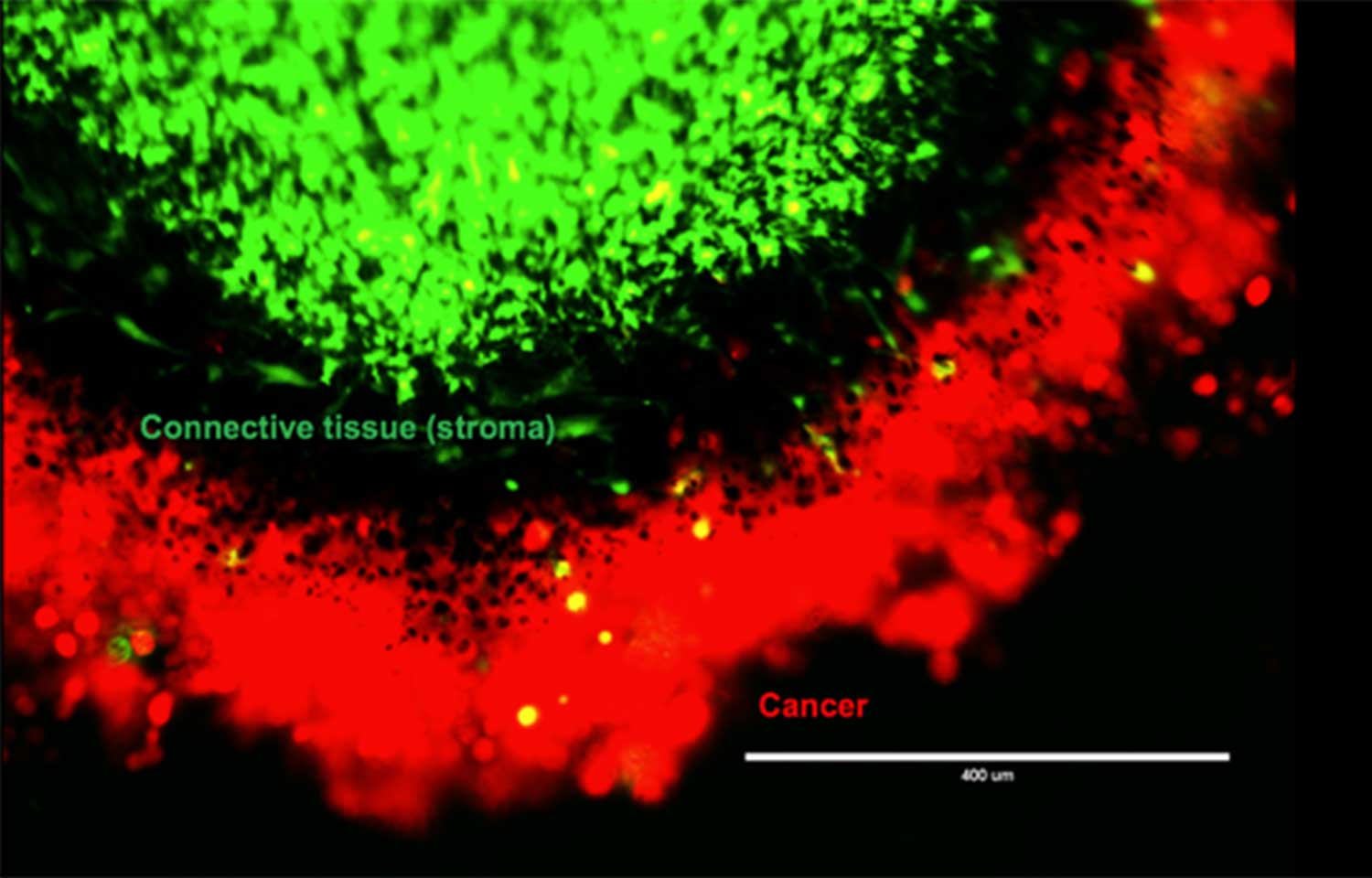

But cancer cells don’t follow these rules. Despite living in a low-nutrient environment, cancer cells draw neighboring stroma cells—the glue-like cells holding our body together—toward them. In this setting you’d expect cells to keep to themselves, not bring more people to the party.

This odd behavior fascinates Petrus R. de Jong, MD, PhD, research assistant professor at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute (SBP), who is studying cancer cells to try to better understand this strange act.

“Scientists are learning more and more about the importance of the tumor’s surrounding environment, called the tumor microenvironment,” says de Jong. “We are finding there are many interactions between stroma and cancer cells. If we could block this cross talk, we might be able to find a new way to treat cancer.”

Many people could benefit from this research, though it is still in its earliest stages. Breast, prostate, ovarian and colorectal cancers are all known to interact with stroma cells. De Jong’s lab is studying pancreatic cancer, which remains one of the deadliest cancers. Less than 10 percent of patients live more than five years after diagnosis. If surgery is not possible, chemotherapy and radiation are the only remaining treatment options.

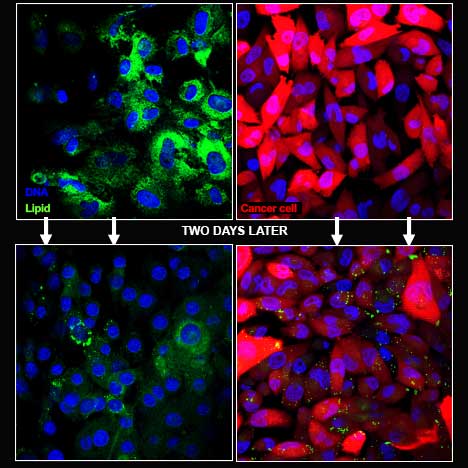

Using pancreatic cancer cells, including cells isolated from patients after surgery, de Jong and his team designed an experiment to better understand why the cancer cells draw stroma cells near. They placed the cancer and stroma cells in a special container that separated the two but still allowed them to interact. After two days, they removed the cells and used special dyes to visualize different parts of the cells. DNA shows up bright blue. Cancer cells, a vibrant red. And a nutrient cells crave—fats, called lipids—shows up an intense green. [To learn more about how fluorescence microscopy works, read our primer.]

Peering under the microscope, de Jong and his team saw green lipids emerge from the stroma and taken up by the red cancer cells.

and were taken up by the red cancer

cells.

“Lipids are a valuable source of energy, so it is unusual for the stroma cells to release this nutrient to the cancer cells,” says de Jong. “It appears the cancer cell is sending out a signal that tells the stroma cells to give them this food.”

To try to determine how the cancer cells were taking up these lipids, de Jong used chemicals to halt autophagy—a process that allows cells to destroy and recycle their own guts. Cancer cells are known to use autophagy to break down elements that aren’t useful any longer and reuse the material as building blocks for growth.

“When the autophagy process was halted, the exchange of lipids stopped,” explains de Jong. “This finding indicates the pancreatic cancer cells forced the stroma cells to start eating themselves, then took up the resulting nutrients.”

De Jong’s team is now focused on the next mystery: how the pancreatic cancer cells are taking up these nutrients. If scientists can identify this process, they might be able to find a medicine that halts cancer cells while leaving healthy cells unharmed, the goal for any cancer treatment.

In other words, they could stop cancer cells from mugging their unsuspecting neighbors.

Read the AACR 2017 abstract detailing this research. For the full poster, contact de Jong at pdejong@sbpdiscovery.org.

Interested in keeping up with SBP’s latest discoveries, upcoming events and more? Subscribe to our monthly newsletter, Discoveries.