There is an art (and science) to creating cell culture models that reflect the complexities of disease. Such models have long been indispensable to parsing the underlying mechanisms of pathology and to preclinical drug discovery.

But art, writes Kevin Tharp, PhD, assistant professor in the Cancer Metabolism and Microenvironment Program, doesn’t always imitate life — at least not when it comes to finding effective cancer therapeutics.

“Just like a machine-learning algorithm trained on irrelevant datasets, efforts to discover anticancer therapeutics are limited by the models we use,” Tharp writes in the British Journal of Pharmacology. “Our drug discovery pipeline works incredibly well but is applied to models that poorly recapitulate in vivo physiology. This may be why drug discovery approaches efficiently identify drugs that work in the context tested and yet often fail to translate into clinical success.”

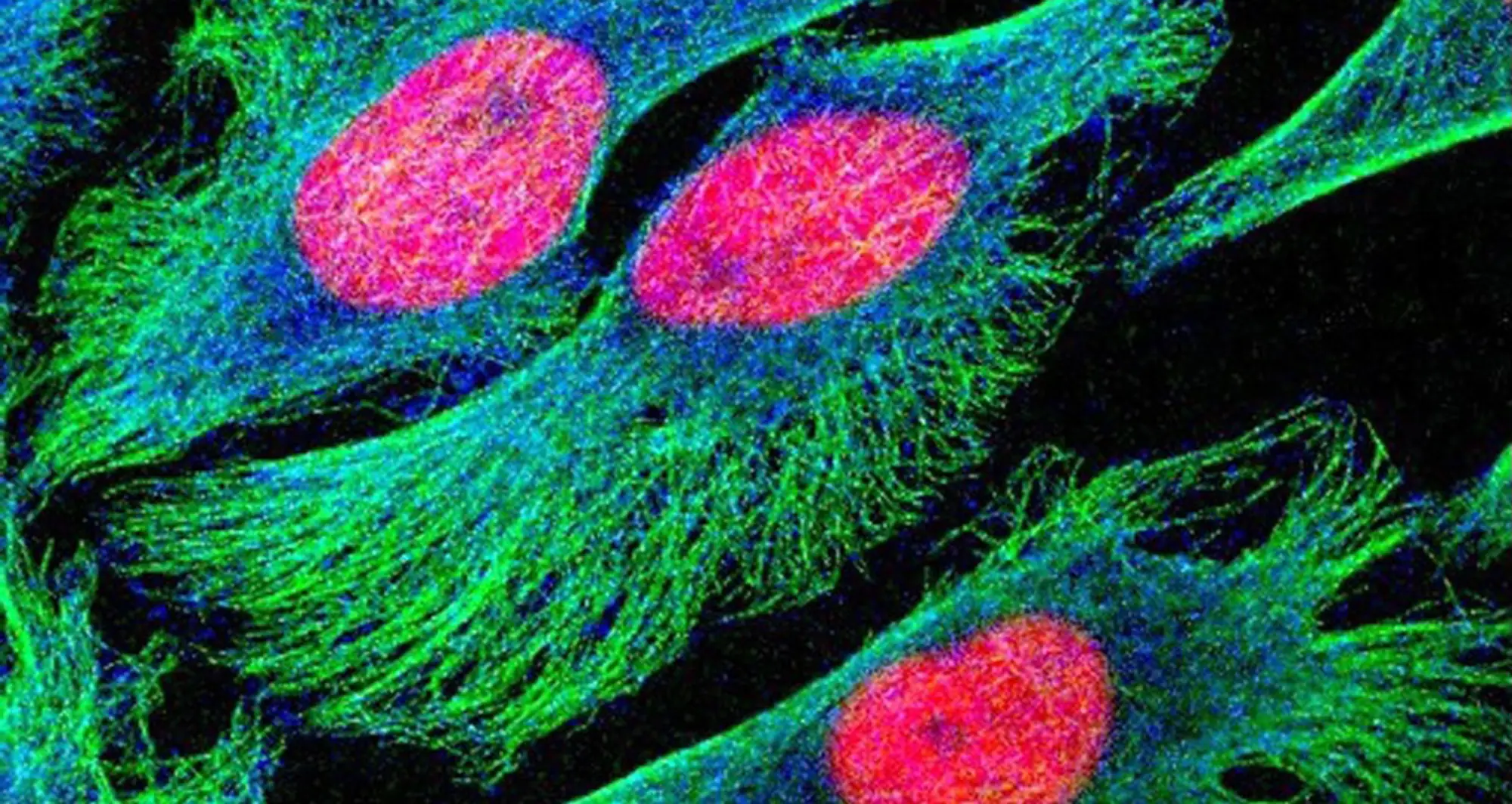

It’s a case of there’s no place like home. Cancer cell models are cultured on plastic in two-dimensions with limited or no diversity of neighbors. Cancer cells in vivo reside in three dimensions, with dynamic and complex interactions with neighboring cells and surroundings, i.e., the tumor microenvironment.

It’s like growing up on Disneyland’s Main Street versus a real-world urban city. Cultured cancer cells simply don’t look or behave exactly the same as cancer cells in an actual tumor. Nor do the investigational molecules being tested as potential therapies.

Tharp suggests a multi-pronged approach: Initially culture target cells using conventional methods, then transfer the cells to new culture formats that enforce distinct, non-genomic cytoskeleton architectures and expression patterns that more closed mimic real life.