Study links the tenascin-C protein to muscle stem cell levels and muscle regeneration, may lead to treatment for frailty

As we age, the muscles we rely on for daily activities tend to become less reliable. With enough decline, even normal movements such as getting out of bed become risky.

Low muscle mass in the elderly—known as sarcopenia—is a major concern for maintaining the quality of life in an aging population. Patients with sarcopenia are more likely to be hospitalized. They also are prone to falls and fractures which can precipitate health declines that often are both swift and steep.

“The progressive loss of skeletal muscle mass and function are indicators of poor survival in patients,” said Alessandra Sacco, PhD, the dean of the Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences and a professor in the Center for Cardiovascular and Muscular Diseases.

“It is absolutely crucial that we are able to develop strategies to maintain muscle as we age.”

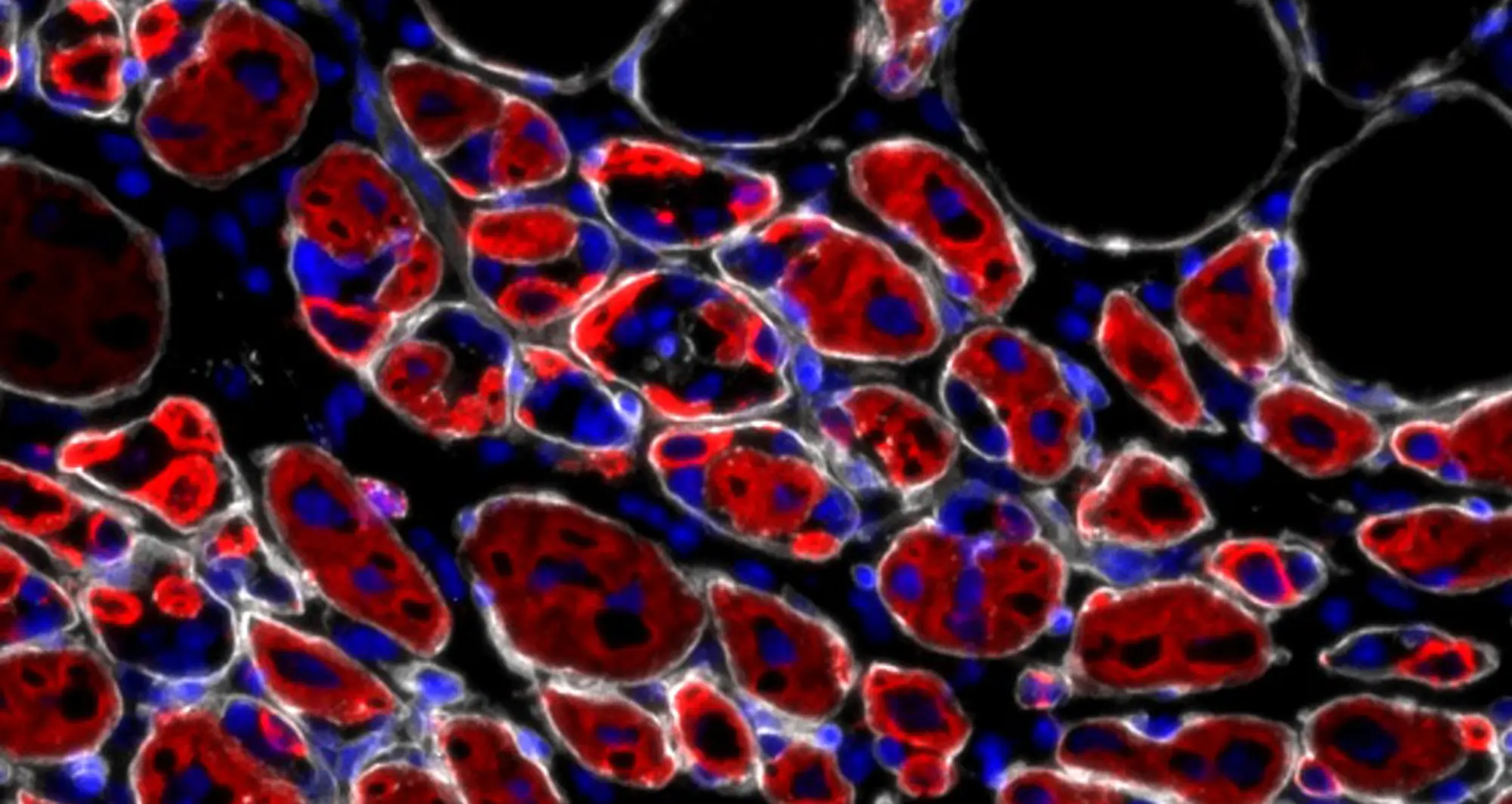

Sacco and a research team at Sanford Burnham Prebys published findings December 5, 2025, in Communications Biology demonstrating how protein in the jelly-like substance between muscle cells promotes a thriving community of functional muscle stem cells needed for efficient muscle regeneration. The scientists also showed that of this protein decrease with age, leading to a decline in muscle stem cells and muscle repair.

The scientists’ prior research into how muscle cells develop from the prenatal stage led them to tenascin-C (TnC), a protein in the gel-like scaffold between cells called the extracellular matrix.

“TnC was one of the genes we found that are specifically elevated at the prenatal stage,” says Lale Cecchini, PhD, a staff scientist in the Sacco lab and co-first author of the manuscript. “This is when organisms are potently expressing proteins used to build the muscles they will need as they grow into adults.”

Alessandra Sacco, PhD, is the dean of the Sanford Burnham Prebys Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences and a professor in the Center for Cardiovascular and Muscular Diseases, and the senior and corresponding author of the study. Image credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys.

During an acute injury or normal wear and tear, the authors’ previous research showed that the organism reuses the same pathways that were active in the embryo to make the tissue in the first place.

“TnC normally is not really expressed in healthy adult muscle, but it goes up rapidly after an injury to reactivate the programs needed for regeneration and repair,” said Sacco, senior and corresponding author of the study.

“We wanted to understand how TnC influenced stem cells that are primarily responsible for muscle regeneration, and how this relationship was affected by aging.”

In the new study, the research team used mice lacking TnC. When compared to normal mice, those without TnC had fewer muscle stem cells.

“The stem cells also were less able to make new stem cells and maintain an adequate population, and this resulted in defects in their ability to repair injured muscle,” said Cecchini.

To better understand the chain of events connecting TnC to muscle stem cell maintenance and function, the scientists looked for TnC’s source as well as the receptor enabling TnC to interact with muscle stem cells.

Lale Cecchini, PhD, is a staff scientist at Sanford Burnham Prebys and the co-first author of the manuscript. Image credit: Sanford Burnham Prebys.

“We found that support cells called fibroadipogenic progenitors were secreting TnC, which made sense given the known role of these during muscle regeneration,” said Sacco.

The researchers then uncovered that TnC communicated with muscle stem cells through a cell receptor called Annexin A2.

“Revealing these players is a bit like identifying musicians in an orchestra,” said Cecchini. “Just as each instrument contributes to the overall composition, now we can learn more about how different signals from each cell type arecoordinated to repair muscle.”

Given that aging reduces skeletal muscle regeneration, the scientists investigated if aging also influenced the amount of TnC in muscle tissue. Their experiments revealed that aged mice had lower levels of TnC, and that their muscle stem cells were less able to migrate to the sites of muscle injury. This defect was correctable by treating aged muscle stem cells with TnC.

“We’ve shown that mice lacking TnC exhibit a premature aging phenotype, and that restoring TnC may be a therapeutic strategy for age-related muscle loss,” said Sacco.

Because it is a large intracellular protein that isn’t suited to medical delivery by pill or injection, more research is needed to develop an effective way to get TnC where it is needed in our muscles. Sacco, Cecchini and their collaborators are working on potential solutions to overcome this supersized shipping dilemma.

“Our overall goal is to contribute to a greater quality of life as we age,” said Cecchini.

“Advances in science, medicine and public health have considerably extended the average lifespan,” said Sacco.

“Now we need to make the same improvements to the healthspan, beginning by addressing frailty, falls and fractures.”

Mafalda Loreti, PhD, a principal scientist at Johnson and Johnson and former postdoctoral researcher in the Sacco lab, is co-first author of the study.

Additional authors include:

- Collin D. Kaufman, Cedomir Stamenkovic, Gabriele Guarnaccia, Chiara Nicoletti, Shawn Delaware, Luca Caputo, Alexandre Colas and Pier Lorenzo Puri from Sanford Burnham Prebys

- Alma Renero from the University of California San Diego

- Anais Kervadec from Avidity Biosciences, Inc.

- Daphne Mayer from Rice University

- Xiuqing Wei from the University of Colorado

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health and Association Française contre les Myopathies.

The study’s DOI is 10.1038/s42003-025-09189-z.