Crucial bodily functions we depend on but don’t consciously think about — things like heart rate, blood flow, breathing, and digestion — are regulated by the neurovascular unit. The neurovascular unit is made up of blood vessels and smooth muscles under the control of autonomic neurons. Yet how the nervous and vascular systems come together during development to coordinate these functions is not well understood. Using human embryonic stem cells, researchers at Sanford-Burnham, University of California, San Diego School of Medicine, and Moores Cancer Center created a model that allows them to track cellular behavior during the earliest stages of human development in real-time. The model reveals, for the first time, how autonomic neurons and blood vessels come together to form the neurovascular unit. The study was published May 21 by Stem Cell Reports.

“This new model allows us to follow the fate of distinct cell types during development, as they work cooperatively, in a way that we can’t in intact embryos, individual cell lines, or mouse models,” said co-senior author of the study David Cheresh, Ph.D., distinguished professor of Pathology, vice-chair for research and development, and associate director for translational research at UC San Diego. “And if we’re ever going to use stem cells to develop new organ systems, we need to know how different cell types come together to form complex and functional structures such as the neurovascular unit.”

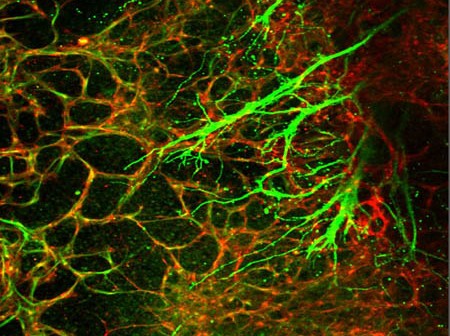

The neurovascular unit comprises three cells types: endothelial cells, which form the blood vessel (vascular) tube; smooth muscle cells, which cover the endothelial tube and control vascular tone; and autonomic neurons, which influence the smooth muscle’s ability to contract and maintain vascular tone.

The study revealed that separate signals produced by endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells are required for embryonic cells to differentiate into autonomic neurons. The researchers discovered that endothelial cells secrete nitric oxide, while smooth muscle cells use the protein T-cadherin to interact with the neural crest, specialized embryonic cells that give rise to portions of the nervous system and other organs. The combination of endothelial cell nitric oxide and the T-cadherin interaction is sufficient to coax neural crest cells into becoming autonomic neurons, where they can then co-align with developing blood vessels.

In addition to answering long-standing questions about human development and improving the odds that scientists will one day be able to generate artificial organs from stem cells, this new insight on the autonomic nervous system also has implications for rare inherited conditions such as neurofibromatosis, tuberous sclerosis, and Hirschsprung’s disease.

“These observations may help to explain certain human disease syndromes in which abnormalities of the nervous system appear to be associated, for previously unclear reasons, with vascular abnormalities,” said co-senior author Evan Snyder, MD, PhD, professor and director of the Center for Stem Cells and Regenerative Medicine at Sanford-Burnham. “Furthermore, we demonstrate here that modeling human development and disease in the lab must take into account multiple cell types in order to reflect the actual human condition. We can no longer rely on merely examining pure populations of one cell type or another.”

Co-authors include Lisette M. Acevedo, Jeffrey N. Lindquist, UC San Diego and Sanford-Burnham; Breda M. Walsh, Peik Sia, UC San Diego; Flavio Cimadamore, Connie Chen, Martin Denzel, Cameron D. Pernia, Barbara Ranscht, and Alexey Terskikh, Sanford-Burnham.

This story was written by Heather Buschman, PhD, Senior Manager of Communications and Media Relations at UC San Diego Health Sciences.