Are you enjoying the summer? Out grilling, swimming and hiking? Beware: those sunny days may come with a cost.

When the sun’s rays touch your skin, they don’t stop there. Ultraviolet (UV) light enters your cells, and photons—tiny particles of light—landing on the proteins and DNA in your cells. With just the right amount of activation energy, proteins change their shape and function, and your DNA becomes damaged, or as we say—mutated. Under normal circumstances, cells use special proteins to repair mutated DNA, but when the repair proteins are damaged, DNA mutations become permanent.

Certain DNA segments called genes are more vulnerable to mutations than others. The BRAF gene, which normally makes a protein that controls cell growth, is mutated in more than 50% of melanomas—the most dangerous type of skin cancer. Melanoma appears when BRAF mutations crop up with other mutations in the same skin cell. For patients with these tumors, drugs that target BRAF and related proteins are often successful at slowing or stopping melanoma growth—but only for a while.

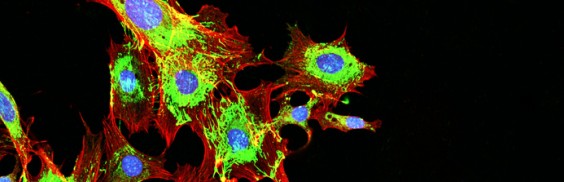

Unfortunately, patients who initially respond to such targeted therapy often relapse. Some patients relapse because their tumors generate a new mutation, making it resistant to the drug. Overall, it may be only a small fraction of cells within the original tumor that develop resistance. So although 99.5% of the cancer cells in a tumor may have a mutated BRAF gene, the other 0.5% can harbor different mutations that either evolved during therapy or were present in the first place, but didn’t drive the initial tumor. For these patients, the bulk of BRAF mutant cancer cells are killed with targeted therapy, but another melanoma can evolve from the remaining 0.5%. This is why combination therapy, where drugs aim for multiple targets, are important.

But targeting every single mutation in a tumor may not be feasible. There will always be a fraction of cells with a different mutation that evolves, making patients vulnerable to a relapse. This is where attacking the tumor from another angle comes into play.

Checkpoint immunotherapies—which have revolutionized the treatment of melanoma—attack tumors independent of their mutational makeup. They work by loosening the brakes of the immune system—brakes that normally prevent immune cells from attacking our own self. Tumors are very good at hiding from the immune system, but with the brakes released, tumors become exposed and are successfully attacked by the immune system, irrespective of their mutational makeup.

But not everyone responds to immunotherapy—and we don’t yet know why. Is it the tumor? Is it the patient’s immune system? There is even evidence that the gut microbiome plays a role. Once we understand why some patients respond and or stop responding to immunotherapy, we can improve selection of patients for therapy, the effectiveness of these treatments and the possible combinations that work best.

So where is skin cancer therapy headed? A combination of checkpoint immunotherapy with targeted therapies, as well as some new tricks we are learning, such as coaching tumor cells to be better recognized by the immune system, are moving the needle.

In my lab at Sanford Burnham Prebys we are dissecting the cell signals that drive cancer. Our studies are guided by data derived from patients’ tumors, coupled with advanced bioinformatics. We seek to understand how physiological processes are modified as cancer develops and how they can be exploited for cancer therapy. For example, we recently demonstrated a connection between the composition of the gut microbiome and the response to immunotherapy, establishing new paradigms, but raising important new questions. Can we better predict who will respond to immunotherapy? Can we enhance the response to immunotherapy by manipulating the gut microbiome? Can we make tumors that don’t initially respond start responding to immunotherapy? The bar is always raised, as one discovery opens so many new avenues to explore and advance our understanding, aspects that members of my lab are working hard on to answer.

Yes—we are making progress. But preventing the initial sun exposure by using protective gear and sunscreens is needed now as much as ever.

Ze’ev Ronai, PhD, professor in Sanford Burnham Prebys’ Tumor Initiation and Maintenance Program, is a world-renowned cancer research expert and recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Society of Melanoma Research. The award recognizes his major and impactful contributions to melanoma research over the course of his career.