Heart disease is the number one killer of Americans. Now, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has awarded a four-year grant totaling nearly half a million dollars to Sanford Burnham Prebys to find medicines that could help people repair damaged heart muscle—and potentially reduce the risk of heart attack or other cardiovascular events.

“Each year we lose far too many loved ones to heart attacks and other heart conditions,” says grant recipient Chris Larson, PhD, adjunct associate professor in the Development, Aging and Regeneration Program at Sanford Burnham Prebys. “Now, we have the opportunity to find medicines that may help more people live long, active lives by strengthening their heart muscles.”

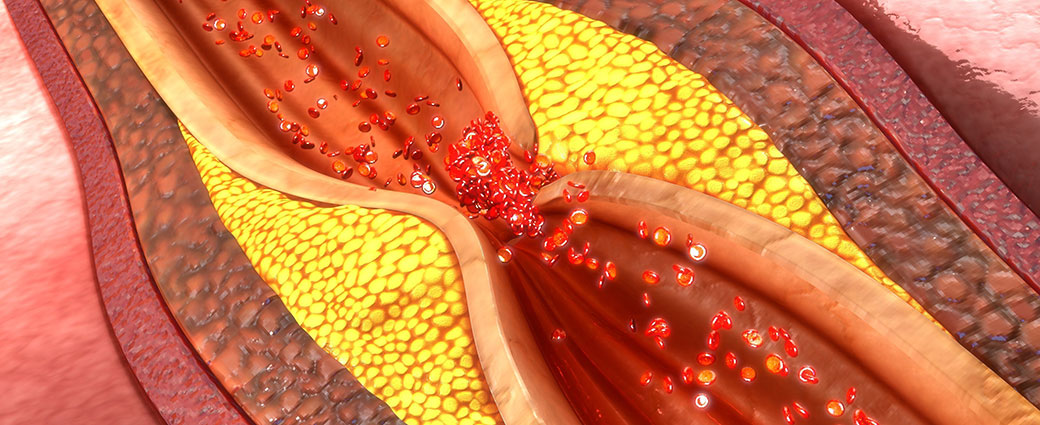

Nearly half of American adults—approximately 120 million people—have cardiovascular disease, according to the American Heart Association and NIH. The condition occurs when blood vessels that supply the heart with oxygen and nutrients become narrowed or blocked, increasing risk of a heart attack, chest pain (angina) or stroke. Current medications for cardiovascular disease can lower blood pressure or thin the blood to minimize risk. Still, five years after a heart attack, 47% of women and 36% of men will die, develop heart failure or experience a stroke. No medicines that repair heart muscle exist.

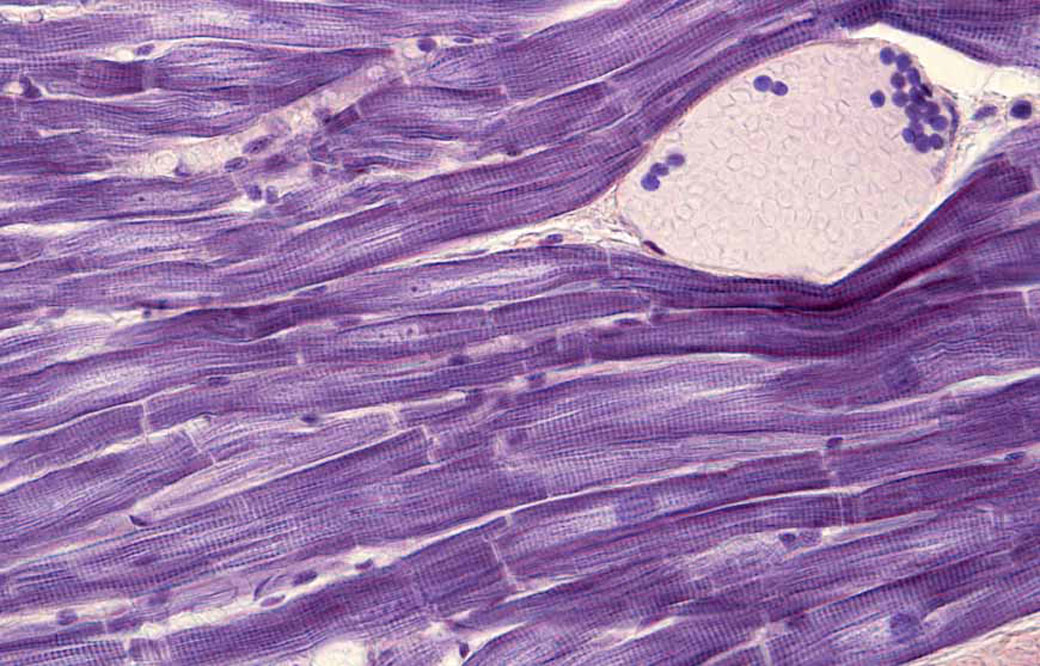

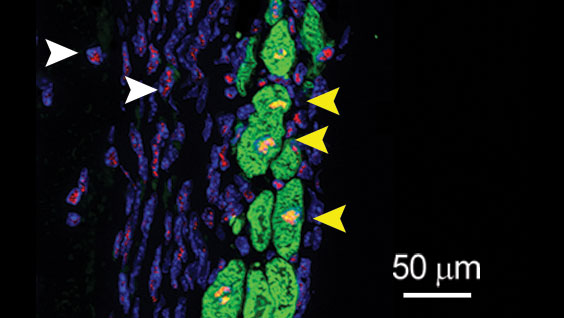

To identify drugs that may stimulate heart muscle growth, Larson and his team will screen hundreds of thousands of compounds against human heart muscle cells, called cardiomyocytes. The work will be done in collaboration with Alexandre Colas, PhD, assistant professor in the Development, Aging and Regeneration Program at Sanford Burnham Prebys, who developed the high-throughput screening system that will be employed.

Once the scientists identify drug candidates that promote heart muscle growth, they will study these compounds in additional cellular and animal models of heart disease in the hopes of uncovering insights into the biology behind the repair process.

“After experiencing a heart attack or other cardiovascular event, many people live in fear that it will happen again,” says Colas. “Today we embark on a journey toward a future where people living with cardiovascular disease don’t have to be afraid of a second heart attack.”