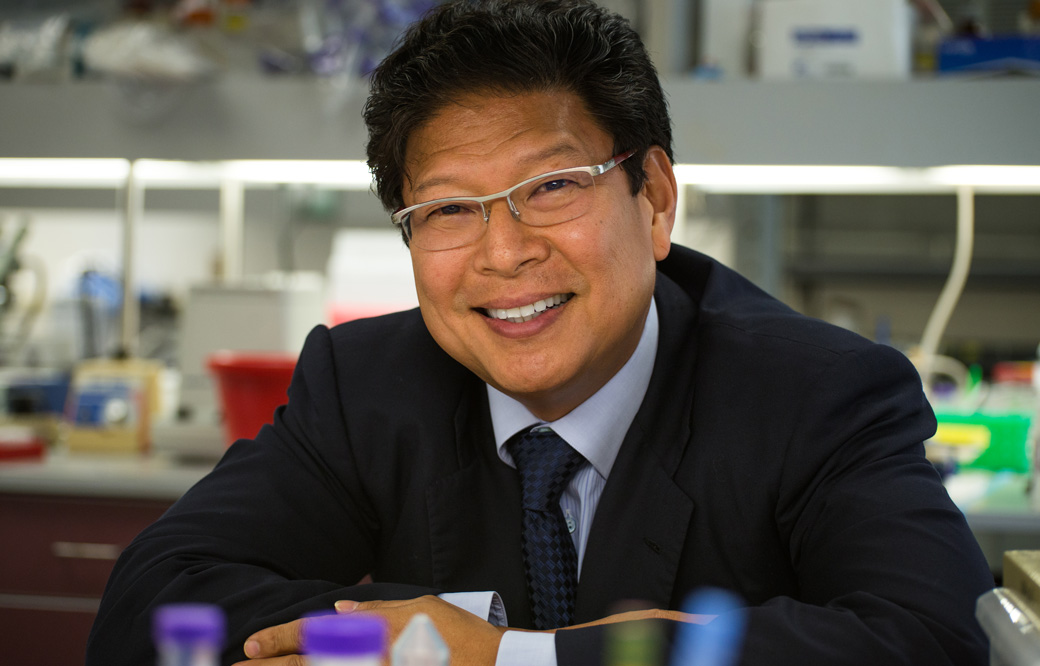

Jerold Chun, MD, PhD, has been awarded a new grant for $250,000 from the Coins for Alzheimer’s Research Trust (CART) Fund, an initiative by Rotary International to encourage exploratory and developmental Alzheimer’s research projects. Chun’s two-year project will explore how virus-like elements in our DNA could play a role in the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

“We are so grateful for the support of CART and the Rotarians,” says Chun. “They’ve shown over the years that small contributions to Alzheimer’s research can add up to make a huge impact.”

Ancient viruses in our genome

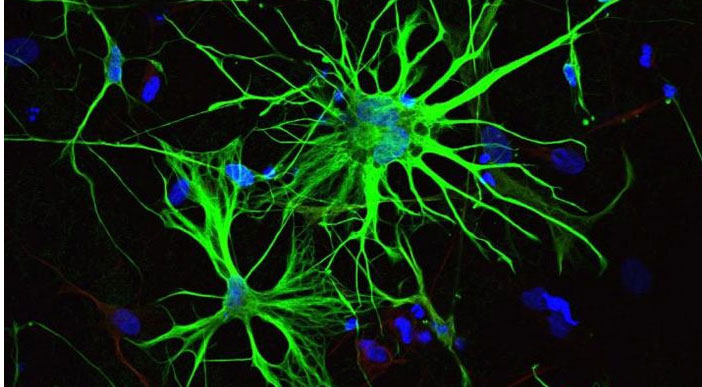

Chun’s project will explore how Alzheimer’s disease relates to endogenous genes in our genome that are very similar to parts of modern viruses. This is because they originated from viruses that infected our ancient ancestors. Over millions of years of evolution, these viruses became a normal part of our genomic makeup.

Chun and other researchers suspect that these viral-like genes may be able to form virus-like particles that move through connections among our brain cells. They hypothesize that this process could promote neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s. “This new grant from CART will help us figure out how these genes and particles work, which is a first step toward thinking about how we might leverage it for treatments.”

Funding research with spare change

CART began in the mid-1990s with an ambitious idea: Could collecting the pocket change of Rotary International members accumulate enough to support Alzheimer’s disease?

The idea was launched in 1996 at Rotary Clubs in South Carolina; and at every meeting, members were asked to donate their loose change to a fund for Alzheimer’s research. The idea exploded from there. Over time, individual clubs started donating portions of their fundraising proceeds, and donations even began to come in from non-Rotary members as CART’s reputation grew.

The fund has awarded more than $10 million in grants to more than 40 institutions since its inception. This year, one of those grants was awarded to Chun to explore a new direction for Alzheimer’s research. This is the first CART grant to be awarded to a Sanford Burnham Prebys researcher.

“Grants like this are important because they give scientists the resources to pursue brand-new research areas,” says Chun. “Every major scientific discovery starts somewhere, and this type of support gives us that starting place, for which we’re really grateful.”