It’s easy to forget about the fist-sized organ in our chest. But the heart is arguably the most important muscle in the body. We can’t live without it, after all.

To help educate the public about heart health and share the latest scientific advances, this month Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute (SBP) invited the San Diego community to a free panel discussion focused on the heart.

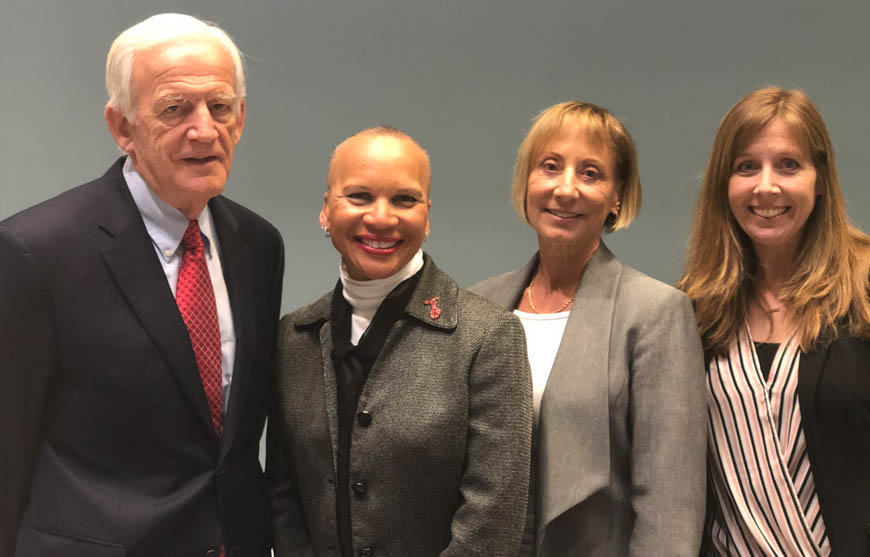

More than 70 community members attended the event, whose speakers included cardiologist Anthony N. DeMaria, MD; Jack White, chair in Cardiology, professor of Medicine, founding director, Sulpizio Cardiovascular Center at UC San Diego Health; Donna Marie Robinson, an individual living with heart failure; and heart researcher Karen Ocorr, PhD, assistant professor, Development, Aging and Regeneration Program at SBP. Jennifer Sobotka, executive director at the American Heart Association San Diego, moderated the discussion.

In a special introduction provided by Rolf Bodmer, PhD, director and professor in the Development, Aging and Regeneration Program at SBP, he explained that his heart research uses model organisms such as the fruit fly. He quipped, “Which some of you didn’t even know had a heart.”

The ensuing discussion was robust and insightful. Below are five important takeaways:

- Heart disease is the number-one killer of Americans. Nearly half of American adults have some form of heart or blood vessel disease.

- Obesity is an epidemic in America. In the 1960s, approximately 13 percent of American adults were obese, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Today, that number has tripled to nearly 40 percent. DeMaria illustrated this point with a colored map showing obesity’s prevalence during each decade, which drew gasps from the crowd.

- Know your numbers. Donna Marie was healthy and fit, so she didn’t think that a fainting episode could have been heart disease. “My cardiologist saved my life,” she said. Now, she encourages everyone to “know your numbers, including your cholesterol level and your blood pressure.”

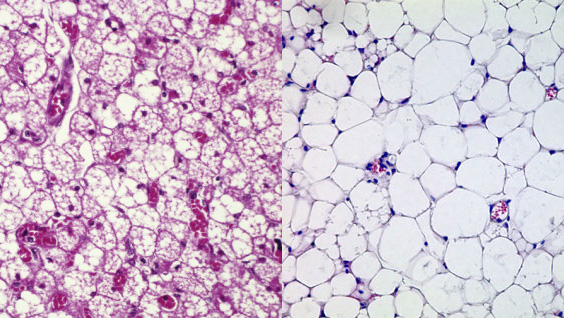

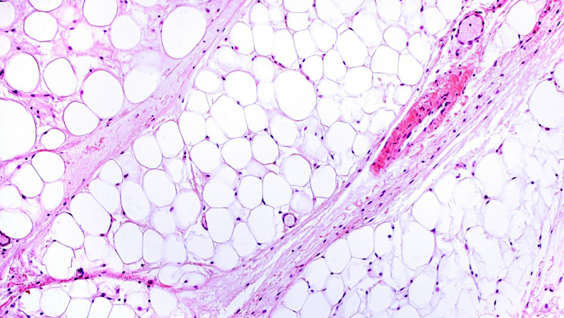

- Rethink swatting that pesky fruit fly. We share 80 percent of disease-causing genes with the tiny insect, including ion channels that keep the heart pumping. For this reason scientists are studying fruit-fly hearts in an effort to learn about the many mysteries of the heart, such as how the rhythm disorder atrial fibrillation (AFib) arises.

- Consider moving to Italy. Just about everyone wants to know which science-backed diet to follow for optimal health. DeMaria explained that the most robust data supports eating a Mediterranean diet rich in fruits, vegetables and olive oil.

Read the La Jolla Light’s coverage of the event.