Skin cancer is one of the most common of all cancers, and melanoma accounts for about 1 percent of skin cancers. However, melanoma causes a large majority of deaths from that particular type of cancer. Alarmingly, rates of skin cancer have been on the rise in the last 30 years. Here in Southern California, our everlasting summer comes with a price. Exposure to sun increases our risk to melanoma.

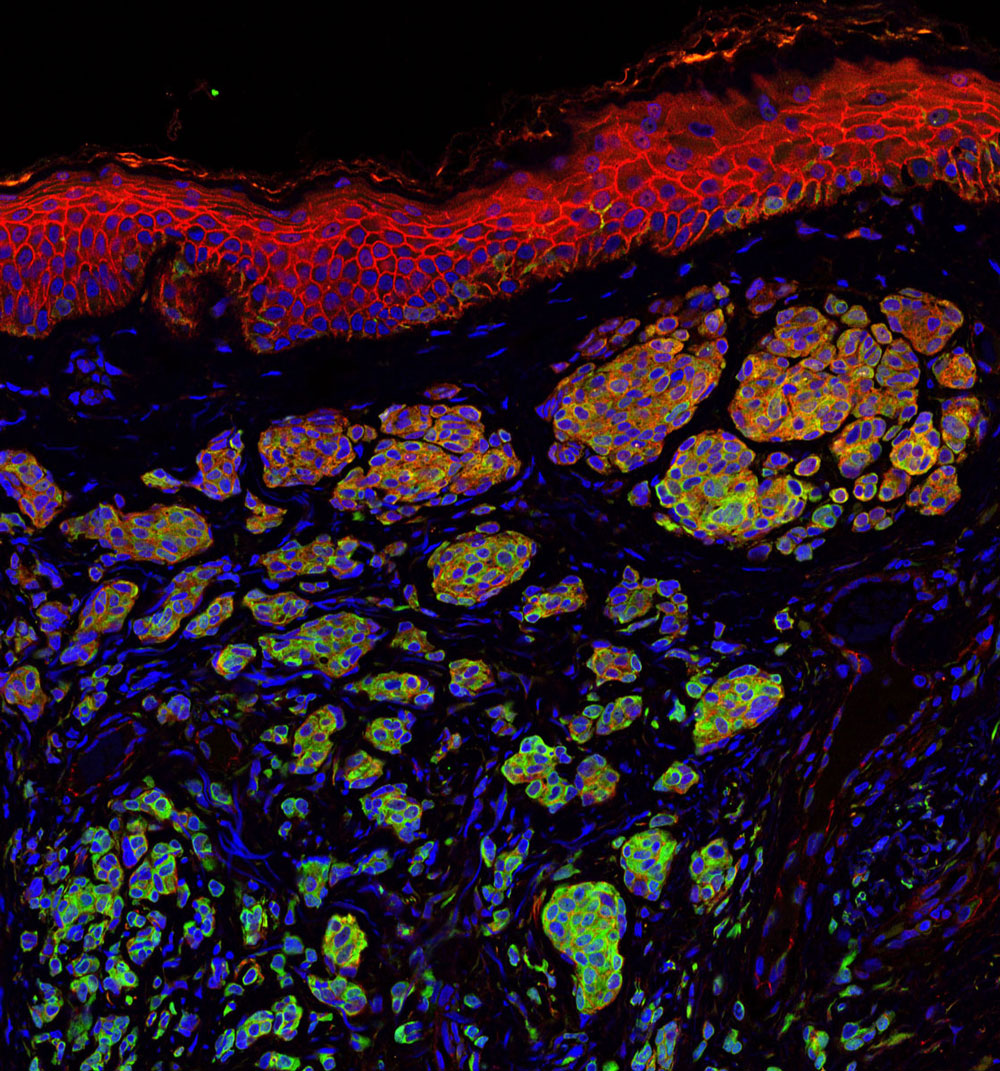

Melanoma occurs when the pigment-producing cells that give color to the skin become cancerous. Symptoms might include a new, unusual growth or a change in an existing mole. Melanomas can occur anywhere on the body.

At Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute (SBP), we have several researchers working on the causes of melanoma and discovering new ways to treat this deadly disease.

Here is a roundup of SBP’s latest research:

Key findings show how melanoma develops in order to identify potential therapeutic targets

Ze’ev Ronai, PhD

Professor and SBP Chief Scientific Advisor

Ronai’s laboratory has been studying how rewired signaling networks can underlie melanoma development, including resistance to therapy and metastatic propensity. One player in that rewiring is a protein called ATF-2, which can switch from its usual tumor-preventive function to become a tumor promoter when combined with a mutation in the human gene called BRAF.

Ronai’s work on a protein, ubiquitin ligases, led to the identification of RNF125 as an important regulator of melanoma resistance to a common chemotherapy drug. RNF125 impacts melanoma resistance by its regulation of JAK2, an important protein kinase which could play an important role in melanoma resistance to therapy.

Work on the ubiquitin ligase Siah2 identified its important role in melanoma growth and metastasis, and its contribution to melanomagenesis. Melanoma is believed to be a multi-step process (melanomagenesis) of genetic mutations that increase cell proliferation, differentiation, and death.

Work in the lab also concern novel metabolic pathways that are exploited by melanoma for their survival, with the goal of identifying combination drug therapies to combat the spread of melanoma. Earlier work on the enzyme PDK1 showed how it can be a potential therapeutic target for melanoma treatment.

Immunotherapy discovery has led to partnership with Eli Lilly

Linda Bradley, PhD

Professor, Immunity and Pathogenesis Program, Infectious and Inflammatory Diseases Center

Bradley’s group is focused on understanding how anti-tumor T cells can be optimized to kill melanoma tumors. They discovered an important molecule (PSGL-1) that puts the “break” on killer T cells, allowing melanoma tumors to survive and grow. Using animal models, they removed this “break” and T cells were able to destroy melanoma tumors. They have extended their studies and found that in melanoma tumors from patients, T cells also have this PSGL-1 “break”. Bradley’s lab has partnered with Eli Lilly to discover drugs that can modulate PSGL-1 activity in human disease that may offer new therapies for patients.

Knocking out a specific protein can slow melanoma growth

William Stallcup, PhD

Professor, Tumor Microenvironment and Cancer Immunology Program

The danger of melanomas is their metastasis to organs, such as the brain, in which surgical removal is not effective. By injecting melanoma cells into the brains of mice, we have shown that the NG2 protein found in host tissues makes the brain a much “friendlier” environment for melanoma growth.

Specifically, NG2 is found on blood vessel cells called pericytes and on immune cells called macrophages. The presence of NG2 on both cell types improves the formation of blood vessels in brain melanomas, contributing to delivery of nutrients and thus to accelerated tumor growth. Genetically knocking out NG2 in either pericytes or macrophages greatly impairs blood vessel development and slows melanoma growth.

Mysterious molecule’s function in skin cancer identified

Ranjan Perera, PhD

Associate Professor, Integrative Metabolism Program

Ranjan’s research uncovered the workings of a mysterious molecule called SPRIGHTLY that has been previously implicated in colorectal cancer, breast cancer and melanoma. These findings bolster the case for exploring SPRIGHTLY as a potential therapeutic target or a biological marker that identifies cancer or predicts disease prognosis.

Drug discovery to help babies has led to a clinical trial at a children’s hospital

Peter D. Adams, PhD

Professor, Tumor Initiation and Maintenance Program

Approximately 1 in 4 cases of melanoma begins with a mole, or nevus. Genetic mutations can cause cells to grow uncontrollably. By investigating how this occurs, we can understand why melanoma develops from some moles, but not others.

Babies born with a giant nevus that covers a large part of the body have especially high risk of melanoma, and the nevus cells can spread into their spine and brain. Adams’ research identified a drug that deters the cells from growing. The drug identified will be used in a clinical trial at Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital in London, England that may help babies with this debilitating disease.

Discovery of a receptor mutation correlates with longer patient survival

Elena Pasquale, PhD

Professor, Tumor Initiation and Maintenance Program

Pasquale’s work has included whether mutations in the Eph receptor, tyrosine kinases, play a role in melanoma malignancy. Eph receptor mutations occur in approximately half of metastatic melanomas. We found that some melanoma mutations can drastically affect the signaling ability of Eph receptors, but could not detect any obvious effects of the mutations on melanoma cell malignancy.

Bioinformatic analysis of metastatic melanoma samples showed that Eph receptor mutations correlate with longer overall patient survival. In contrast, high expression of some Eph receptors correlates with decreased overall patient survival, suggesting that Eph receptor signaling can promote malignancy.