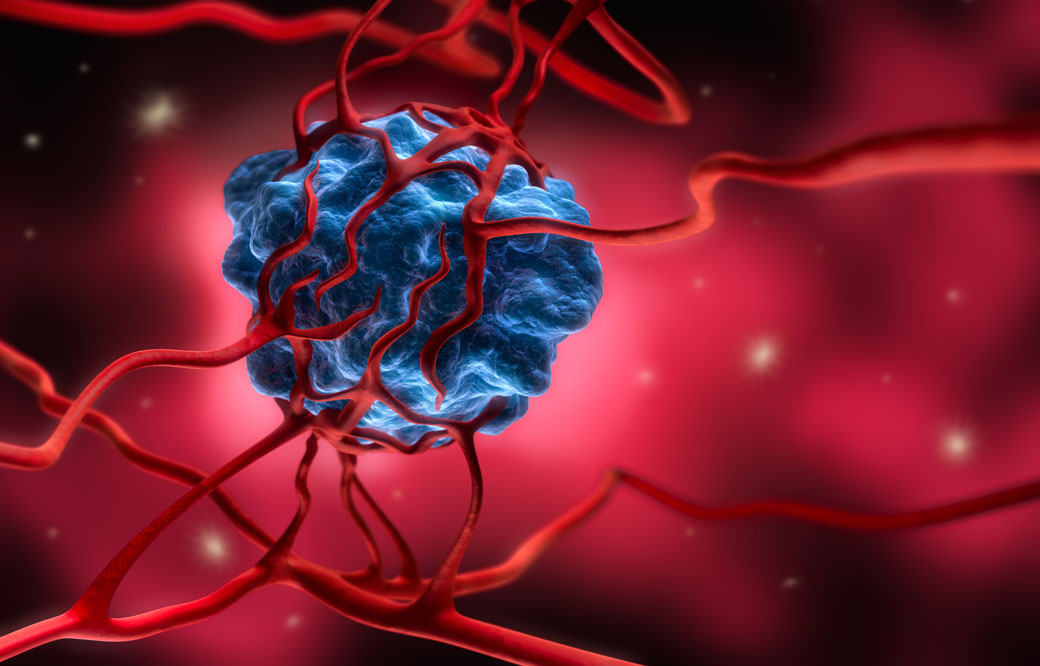

Drug candidate blocks autophagy, a cellular recycling process that cancer cells hijack as a way to resist treatment

Scientists at Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute have designed a next-generation drug, called SBP-7455, which holds promise as a treatment for triple-negative breast cancer—an aggressive cancer with limited treatment options. The drug blocks a cellular recycling process called autophagy, which cancer cells hijack as a way to resist treatment. The proof-of-concept study was published in the Journal of Medicinal Chemistry.

“Scientists are now learning that autophagy is one of the main ways that cancer cells are able to survive, even in the presence of growth-blocking treatments,” says Huiyu Ren, a graduate student in the laboratory of Nicholas Cosford, PhD, at Sanford Burnham Prebys, and first author of the study. “If all goes well, we hope this compound will stop cancer cells from turning on autophagy and allow people with triple-negative breast cancer to benefit from their treatment for as long as possible.”

Cells normally use autophagy as a way to recycle waste products. However, when cancer cells’ survival is threatened by a growth-blocking treatment, this process is often “revved up” so the cancer cell can continue to receive nutrients and keep growing. Certain cancers are more likely to rely on the autophagy process for survival, including breast, pancreatic, prostate and lung cancers.

“While this study focused on triple-negative breast cancer, an area of great unmet need, we are actively testing this drug’s potential against more cancer types,” says Cosford, professor and deputy director in the National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated Cancer Center at Sanford Burnham Prebys and senior author of the study. “An autophagy-inhibiting drug that stops treatment resistance from taking hold would be a great addition to an oncologist’s toolbox.”

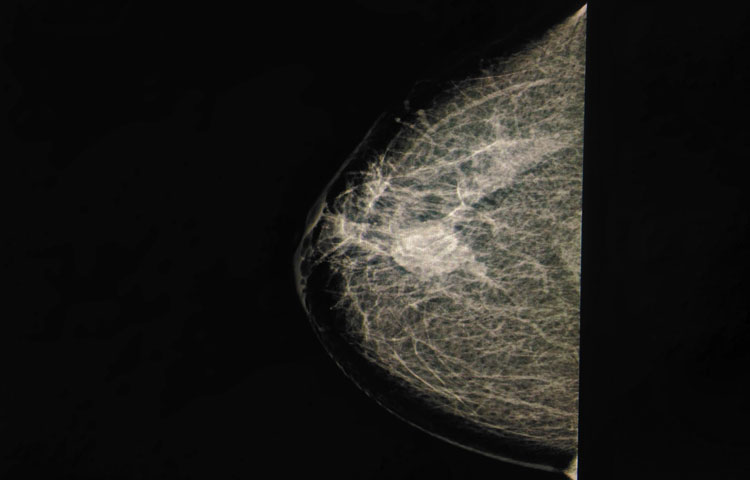

About 15% to 20% of all breast cancers are triple negative, which means they do not respond to hormonal therapy or targeted treatments. The cancer is currently treated with surgery, chemotherapy and radiation, and is deadlier than other breast cancer types. If the tumor returns, other treatments such as PARP inhibitors or immunotherapy are considered. People under the age of 50 are more likely to have triple-negative breast cancer, as well as women who are Black, Hispanic, and/or have an inherited BRCA mutation.

An optimized drug

In this study, the scientists optimized a first-generation drug they created in 2015. The result is a compound called SBP-7455 that blocks two autophagy proteins, ULK1 and ULK2. SBP-7455 exhibits promising bioavailability in mice and reduces autophagy levels in triple-negative breast cancer cells, resulting in cell death. Importantly, combining the drug with PARP inhibitors, which are currently used to treat people with recurrent triple-negative breast cancer, makes the drug even more effective.

“We are hopeful that we have found a new potential therapy for people living with triple-negative breast cancer,” says Reuben Shaw, PhD, a study author and professor in the Molecular and Cell Biology Laboratory and director of the NCI-designated Cancer Center at the Salk Institute. “We envision this drug being used in combination with targeted therapies, such as PARP inhibitors, to prevent cancer cells from becoming treatment resistant.”

Next, the scientists plan to test the drug in mouse models of triple-negative breast cancer to confirm that the compound can stop tumor growth in an animal model. In parallel, they will continue optimization efforts to ensure the drug has the greatest chance of clinical success.

“Triple-negative breast cancer is one of the hardest cancers to treat today,” says Ren. “I hope that our research marks the start of a path to successful treatment that helps more people survive this aggressive cancer.”

Additional study authors include Nicole A. Bakas, Mitchell Vamos, Allison S. Limpert, Carina D. Wimer, Lester J. Lambert, Lutz Tautz, Maria Celeridad and Douglas J. Sheffler of Sanford Burnham Prebys; Apirat Chaikuad and Stefan Knapp of the Buchmann Institute for Molecular Life Sciences and Goethe-University Frankfurt; and Sonja N. Brun of the Salk Institute.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (P30CA030199, T32CA211036), Epstein Family Foundation, Larry L. Hillblom Foundation (2019-A-005-NET), Pancreatic Cancer Action Network (19-65-COSF), SGC—a registered charity that receives funds from AbbVie, Bayer Pharma AG, Boehringer Ingelheim, Canada Foundation for Innovation, Eshelman Institute for Innovation, Genome Canada through Ontario Genomics Institute [OGI-196], EU/EFPIA/OICR/McGill/KTH/Diamond, Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking (875510), Janssen, Merck KGaA, Merck & Co, Pfizer, São Paulo Research Foundation-FAPESP, Takeda, and Wellcome.

The study’s DOI is 0.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c00873.