The SPARK program aims to train tomorrow’s experts in regenerative medicine.

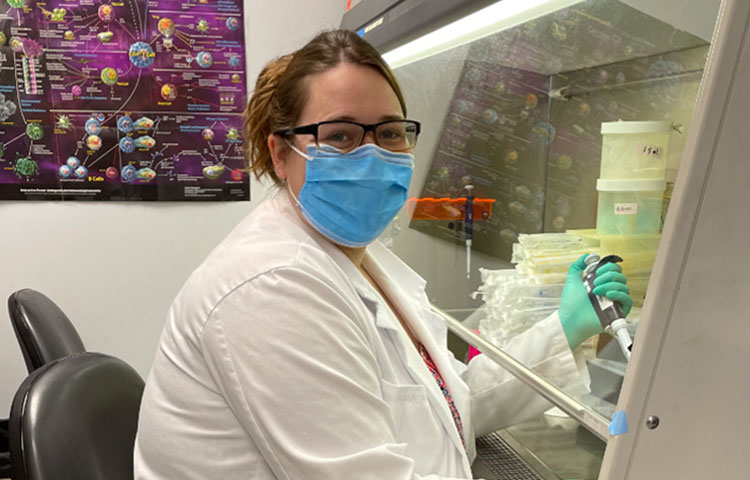

Sanford Burnham Prebys welcomed its second cohort of SPARK interns this summer. SPARK, which stands for Summer Program to Accelerate Regenerative Medicine Knowledge, is an initiative by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) to provide research opportunities for high schoolers from underrepresented groups throughout California. The SPARK interns completed a six-week project under the supervision of a faculty mentor and presented their work to scientists at the Institute.

“It was great connecting with everybody in the lab and learning about their background, why they came here, and what they’re trying to learn,” says SPARK intern Katelyn Gelle. “Getting to compare their experiences with mine was really inspiring, because there’s so much to learn from other people who love science.”

Sanford Burnham Prebys is one of 11 institutions throughout California that hosts SPARK interns, and the program was funded by a grant from CIRM. This year’s interns were the second cohort of five to be supported by that grant.

“Last year’s SPARK program was a great success, and we’re so happy to be able to keep up the momentum with another group of bright, talented interns,” says Program Director Paula Checchi, PhD Checchi is an administrator in the Office of Education, Training and International Services at Sanford Burnham Prebys. Paula developed and oversaw the educational components of the internship program.

SPARK students worked in labs learning the hands-on techniques that scientists use to study degenerative diseases—with the goal of finding new approaches to treat the millions of people affected by these conditions. Completing an individual project with a faculty mentor gave interns the chance to experience the real-life ins and outs of research.

“It was really unexpected how much refining and editing it takes to get a result from experiments” says SPARK intern Medha Nandhimandalam. “You don’t cure cancer in a day.”

The internship also included other educational opportunities, such as a tour of the Sanford Consortium for Regenerative Medicine and a Diversity in Science seminar series. The program culminated in a final celebration at the Institute where students had the chance to share the results of their work and what they’ve learned from their time in the lab.

“The lab itself was my favorite part of the experience – not just the academic side but the whole lifestyle and experience of working with the scientists and spending time with them day to day” says SPARK intern Rini Khandelwal.

As a final capstone to the internship experience, the students will travel to Los Angeles August 8–9 for CIRM’s annual SPARK conference, where they presented their work and networked with interns from other Institutions across the state.