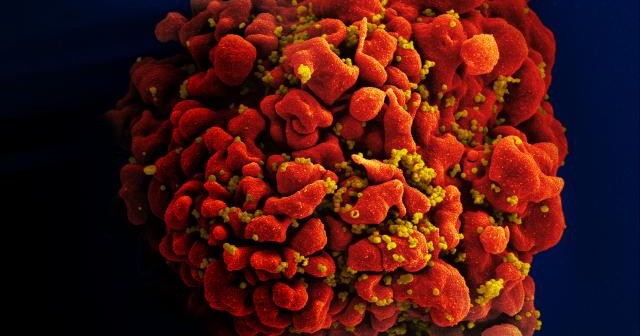

Research has shown that methamphetamine (METH) use among HIV-positive individuals may be as high as 25%, compared with a national average of less than one percent. On its own, METH can cause irreparable physical, psychological, and social damage to individuals who abuse or become dependent on the drug. For HIV-positive patients, particularly individuals undergoing treatment with antivirals, the combined effects of METH and HIV infection on the central nervous system are particularly concerning.

A new study by SBP researchers evaluates the neuronal damage caused by HIV proteins, METH, and combinations of antiretroviral drugs (ARVs). Combinations of ARVs are the most common treatment for HIV-positive individuals, and are credited for increasing the survival of patients to near normal life spans. The results, published in Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, are surprising.

- The overall positive effect of ARVs—keeping patients alive—comes with a downside. Certain ARV drug combinations are neurotoxic.

- Some combinations of HIV, ARVs and METH increase neuronal impairment, while others have no additive effect. And the results are unpredictable.

“Our finding that ARVs can be neurotoxic is concerning,” said Marcus Kaul, PhD, associate professor in the Immunity and Pathogenesis Program at SBP. “We already know the virus on its own can cause a condition called HAND, which stands for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. That’s a fancy way of describing changes in memory, concentration, attention, and motor skills that affect up to 50% of HIV-positive patients.”

“Since the goal is to keep HIV-positive patients alive and healthy, it’s important to learn if the treatments we use to prolong life have unwanted side effects. Our research suggests that some ARV combination therapies aggravate neurocognitive decline. ”

Adding methamphetamine to the mix further complicates matters.

“We found that even though METH on its own is toxic to neurons, with some combinations of ARVs, we observe increased neuronal impairment, but in other combinations there is no additive affect. This means that the neurocognitive effects of METH may depend on the ARV combination prescribed to the patient.”

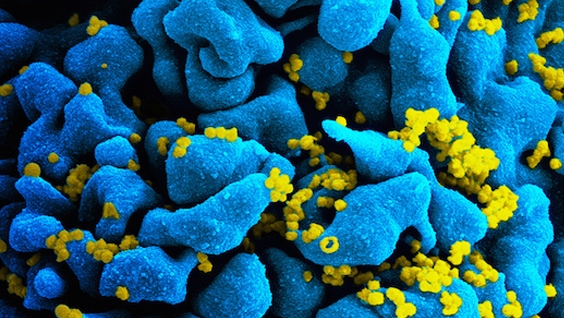

The study tested four of the most commonly used ARTs in the presence and absence of METH and gp120, a neurotoxic HIV protein that sits on the surface of the virus but can also be released from infected cells. The researchers used an in vitro system to assess neuronal damage produced by various combinations of the drugs and virus protein. Damage was measured by assessing the number of neurons and quantifying components of their processes and synapses. The analysis also included measurement of neuronal ATP levels—the main energy source of cells. Measuring ATP levels is a well-established method for evaluating toxicity. A reduction in ATP levels is indicative of cell damage.

“In a perfect world we would be able to predict which ARV therapy combinations are best suited to HIV-positive individuals prone to recreational drug use. While we are probably a few years from this degree of personalizing HIV treatment, in the short term the information adds to our understanding of the pathways and mechanisms that lead to neurocognitive decline and dementia, so the lessons we learn may ultimately be applied more broadly to neurological disorders,” Kaul added.