A screen of more than 1,600 Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved drugs performed at SBP’s Conrad Prebys Center for Chemical Genomics (Prebys Center) has revealed new therapeutic avenues that could lead to an Alzheimer’s disease treatment.

The findings come from a collaboration between SBP scientists and researchers at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine, Leiden University Medical Center and Utrecht University in the Netherlands and were published in Cell Stem Cell.

The hunt is on for an effective treatment for Alzheimer’s, a memory-robbing disease that is nearing epidemic proportions as the world’s population ages. Nearly six million people in the U.S. are living with Alzheimer’s disease. This number is projected to rise to 14 million by 2060, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Scientists have known for many years that a protein called tau accumulates and creates tangles in the brain during Alzheimer’s disease. Additional research is revealing that altered cholesterol metabolism in the brain is associated with Alzheimer’s. But the relationship between these two clues is unknown.

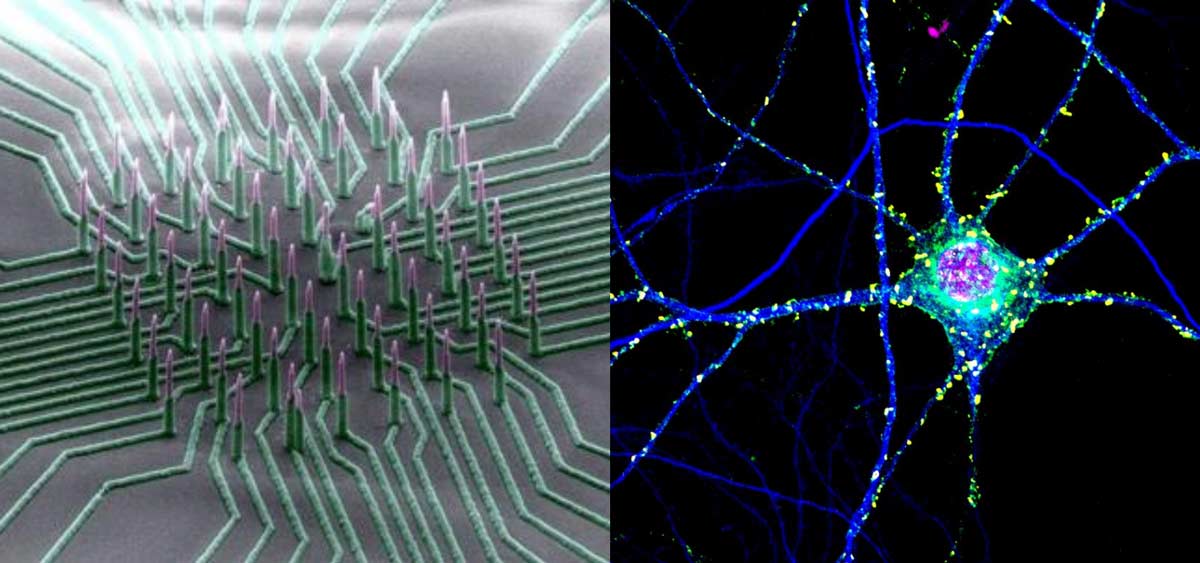

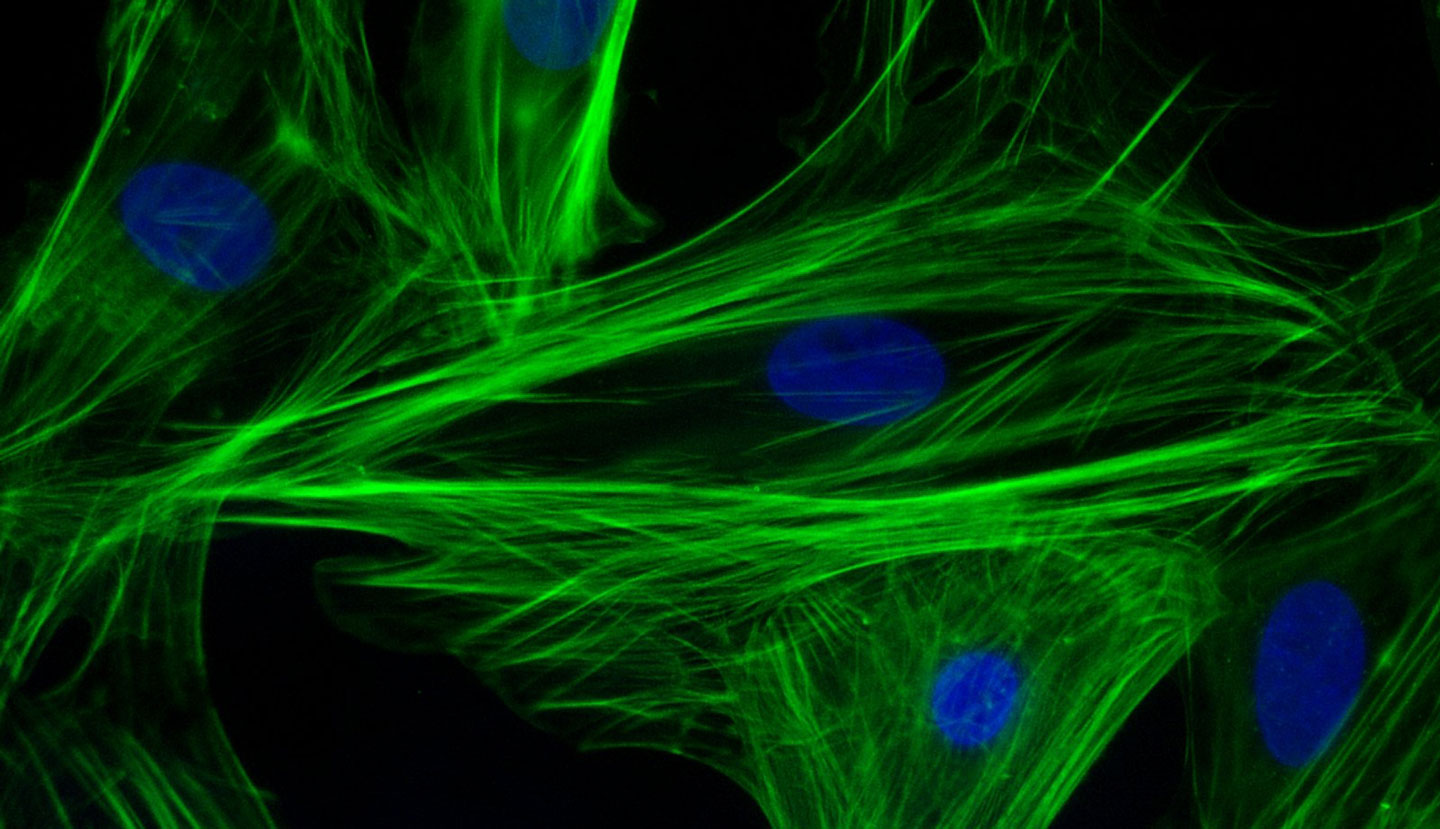

By testing a library of FDA-approved drugs against induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) neurons created from people with Alzheimer’s disease, the scientists were able to identify 42 compounds that reduced the level of phosphorylated tau, a form of tau that contributes to tangle formation. The researchers further refined this group to only include cholesterol-targeting compounds.

A detailed study of these drugs showed that their effect on tau was mediated by their ability to lower cholesteryl esters, a storage product of excess cholesterol. These results led them to an enzyme called CYP46A1, which normally reduces cholesterol. Activation of this enzyme by the drug efavirenz (brand names Sustiva® and Stocrin®) reduced cholesterol esters and phosphorylated tau in these neurons, making it a promising therapeutic target for Alzheimer’s disease. Further mapping of the enzyme’s action(s) within a cell could reveal even more therapeutic targets.

“Our Prebys Center is designed to be a comprehensive resource that allows basic research—whether conducted at SBP, academic and nonprofit research institutions or industry—to be translated into medicines for diseases that urgently need better treatments,” says study author Anne Bang, PhD, director of Cell Biology at the Conrad Prebys Center for Chemical Genomics at SBP. “We are proud that the Prebys Centers’ drug discovery technologies helped reveal new paths that could lead to a potential treatment for Alzheimer’s, one of the most devastating diseases of our time.”

The senior author of the study is Lawrence S. B. Goldstein, PhD, distinguished professor at the University of California San Diego (UC San Diego) and scientific director of the Sanford Consortium for Regenerative Medicine. The co-first authors are Vanessa Langness, a PhD graduate student in Goldstein’s lab, and Rik van der Kant, PhD, a senior scientist at Vrije University in Amsterdam and former postdoctoral fellow in Goldstein’s lab.

Additional study authors include Cheryl M. Herrera, Daniel Williams, Lauren K. Fong and Kevin D. Rynearson, UC San Diego; Yves Leestemaker, Huib Ovaa, Evelyne Steenvoorden and Martin Giera of Leiden University Medical Center; Jos F. Brouwers and J. Bernd Helms; Utrecht University; Steven L. Wagner, UC San Diego and Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System.

Funding for this research came, in part, from the Alzheimer Netherlands Fellowship, ERC Marie Curie International Outgoing Fellowship, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (5T32AG000216-24, IRF1AG048083-01) and the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (RB5-07011).

Read more in UC San Diego’s press release.