More than 25 years after targeting a member of this superfamily of proteins led to groundbreaking treatments for several autoimmune diseases including rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease, San Diego scientists note a resurgence of interest in research to find related new drug candidates.

In 1998, the same year “Footloose” debuted on Broadway, REMICADE® (infliximab) was approved by the FDA for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. This was the first monoclonal antibody ever used to treat a chronic condition, and it upended the treatment of Crohn’s disease.

Research published in February 2024 demonstrated better outcomes for patients receiving infliximab or similar drugs right after diagnosis rather than in a “step up” fashion after trying other more conservative treatments such as steroids.

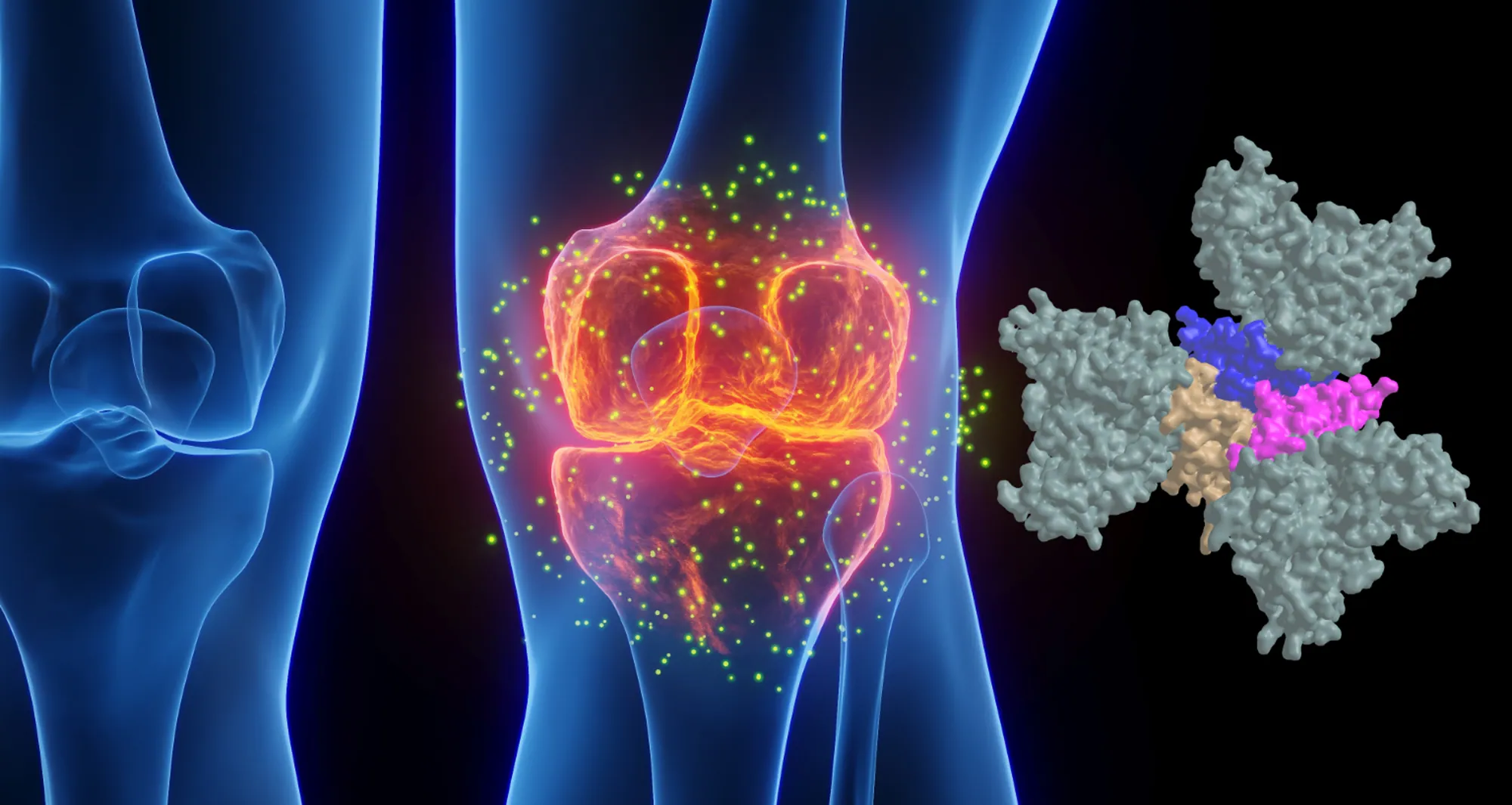

Infliximab and ENBREL® (etanercept) — also approved in 1998 to treat rheumatoid arthritis — were the first FDA-approved tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) inhibitors. TNF is part of a large family of signaling proteins known to play a key role in developing and coordinating the immune system.

The early success of infliximab and etanercept generated excitement among researchers and within the pharmaceutical industry at the possibility of targeting other members of this protein family. They were interested in finding new protein-based (biologics) drugs to alter inflammation that underlies the destructive processes in autoimmune diseases.

As “Footloose” made it back to Broadway in 2024 for the first time since its initial run, therapies targeting the TNF family are in the midst of their own revival. Carl Ware, PhD, a professor in the Immunity and Pathogenesis Program at Sanford Burnham Prebys, and collaborators at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology and biotechnology company Inhibrx, report in Nature Reviews Drug Discovery that there is a resurgence of interest and investment in these potential treatments.

“Many of these signaling proteins or their associated receptors are now under clinical investigation,” said Ware. “This includes testing the ability to target them to treat autoimmune and inflammatory diseases, as well as cancer.”

Today, there are seven FDA-approved biologics that target TNF family members to treat autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. There also are three biologics and two chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell-based therapies targeting TNF members for the treatment of cancer. This number is poised to grow as Ware and his colleagues report on the progress of research and many clinical trials to test new drugs in this field and repurpose currently approved drugs for additional diseases.

“The anticipation levels are high as we await the results of the clinical trials of these first-, second- and — in some cases — third-generation biologics,” said Ware.

Ware and his coauthors also weighed in on the challenges that exist as scientists and drug companies develop therapies targeting the TNF family of proteins, as well as opportunities presented by improvements in technology, computational analysis and clinical trial design.

Carl Ware, PhD, is a professor in the Immunity and Pathogenesis Program at Sanford Burnham Prebys.

“There are still many hurdles to get over before we truly realize the potential of these drugs,” noted Ware. “This includes the creation of more complex biologics that can engage several different proteins simultaneously, and the identification of patient subpopulations whose disease is more likely to depend on the respective proteins being targeted.

“It will be important for researchers to use computational analysis of genetics, biomarkers and phenotypic traits, as well as animal models that mimic these variables. This approach will likely lead to a better understanding of disease mechanisms for different subtypes of autoimmune conditions, inflammatory diseases, and cancer, enabling us to design better clinical trials where teams can identify the appropriate patients for each drug.”