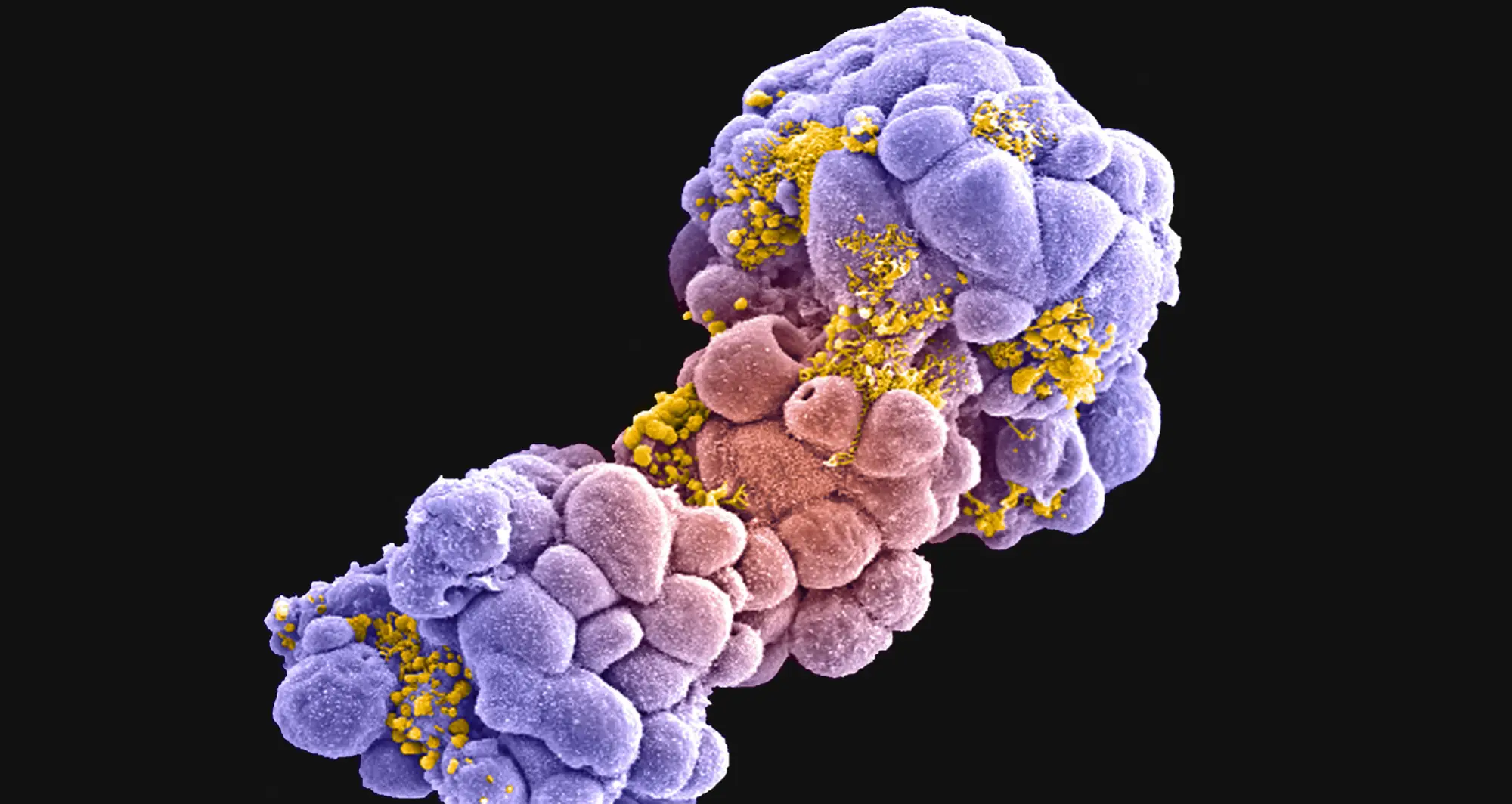

Cancer researchers are setting their sights on a new kind of cancer treatment that targets the tumor’s surrounding environment, called the tumor microenvironment, in contrast to targeting the tumor directly.

To learn more about this approach, we spoke with cancer experts Jorge Moscat, PhD, director and professor in the Cancer Metabolism and Signaling Networks Program at Sanford Burnham Prebys; and Maria Diaz-Meco, PhD, professor in the Cancer Metabolism and Signaling Networks Program at Sanford Burnham Prebys. Both scientists recently authored a review article centered on a family of cancer-linked proteins that regulate the tumor’s microenvironment. The paper was published in Cancer Cell.

What is the tumor microenvironment exactly?

Moscat: Just like every person is surrounded by a supportive community—their friends, family or teachers—every tumor is surrounded by a microenvironment. This ecosystem includes blood vessels that supply the tumor with nutrients; immune cells that the tumor has inactivated to evade detection; and stroma, glue-like connective tissue that holds the cells together and provides the tumor with nutrients.

Diaz-Meco: These elements are similar to the three legs of a stool. If we remove all three legs, we can deliver a deadly blow to the tumor. FDA-approved drugs exist that target blood vessel growth and reactivate the immune system to destroy the tumor. The final frontier is targeting the stroma.

When did scientists realize it’s important to focus on the tumor’s surroundings—not the tumor itself?

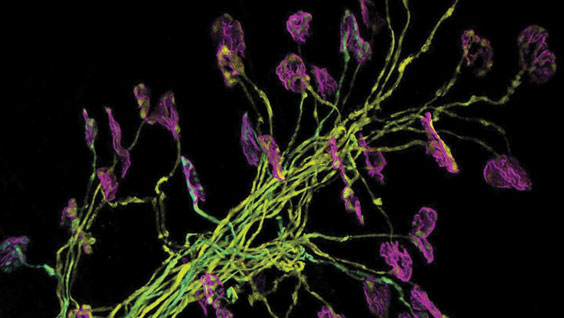

Diaz-Meco: Scientists have known for more than a century that the tumor’s surroundings are different from normal cells. The tissue surrounding a tumor is inflamed—tumors are often called “wounds that never heal”—and their metabolism is radically different from healthy cells.

Moscat: The discovery of oncogenes—genes that can lead to cancer—in the 1970s shifted the field’s focus to treatments that target the tumor directly. These targeted treatments work incredibly well, but only for a short time. Cancer researchers are realizing that tumors quickly adapt to this roadblock and become treatment resistant. In addition, many oncogenes are difficult to target, earning the title “undruggable.” As a result, cancer researchers are returning their focus to the tumor microenvironment—especially the stroma. Only a handful of stroma-targeting drugs are in development. None are FDA approved.

Which cancers could benefit most from a stroma-targeting drug?

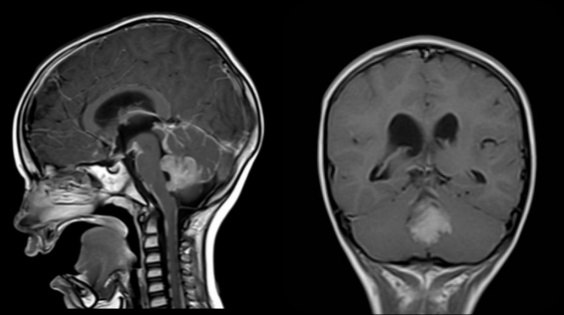

Moscat: Pancreatic, colorectal and liver cancers stand to benefit most from a stroma-targeting drug. For example, 90% of a pancreatic tumor consists of stroma—not cancer cells. Combined, these cancers are responsible for more than 20% of all cancer deaths in the U.S. each year.

What is the focus of your lab’s research?

Diaz-Meco: Our lab studies the cross talk between tumors and their environment. This conversation is very complex. In addition to “talking” with the tumor, the stroma also “speaks” with the immune system. We are working to map these interactions so we can create drugs that silence this conversation—or change it. For example, we recently showed—in a mouse model that faithfully recapitulates the most aggressive form of human colorectal cancer—that by altering the stroma’s interactions with the immune system, we might make tumors vulnerable to immunotherapy.

What do new insights into the tumor microenvironment mean for cancer drug development?

Moscat: It’s likely that the ultimate cancer “cure” won’t be just one drug that kills the tumor cells, but a combination of therapies. I expect this will be a three-part combination treatment that stops blood vessel growth, activates the immune system to attack the tumor and targets the stroma.

Additionally, this research shows that experimental models of cancer drug development need to take the tumor microenvironment into account. Many current models use mice that lack an immune system—in order to get the tumor to grow—or focus on the tumor in isolation. Based on our knowledge of the tumor microenvironment, this isn’t an accurate representation of human disease.

Diaz-Meco: In our lab, we have created several animal models of cancers that preserve the immune system and mirror tumor progression. In addition to better modeling human disease, this also allows us to study cancer from its earliest beginnings. This work could lead to early interventions—before the cancer has become large and hard to treat.

Anything else you’d like to add?

Moscat: We are truly in the golden age of cancer biology. We understand more than we ever have before. New technologies are allowing us to obtain an unprecedented amount of information—we can even map every gene that is “turned on” in a single cancer cell. I am incredibly hopeful for the future.

Learn more about the future of cancer treatment by attending our next “Conquering Cancer” event at the Fleet Science Center. Details.