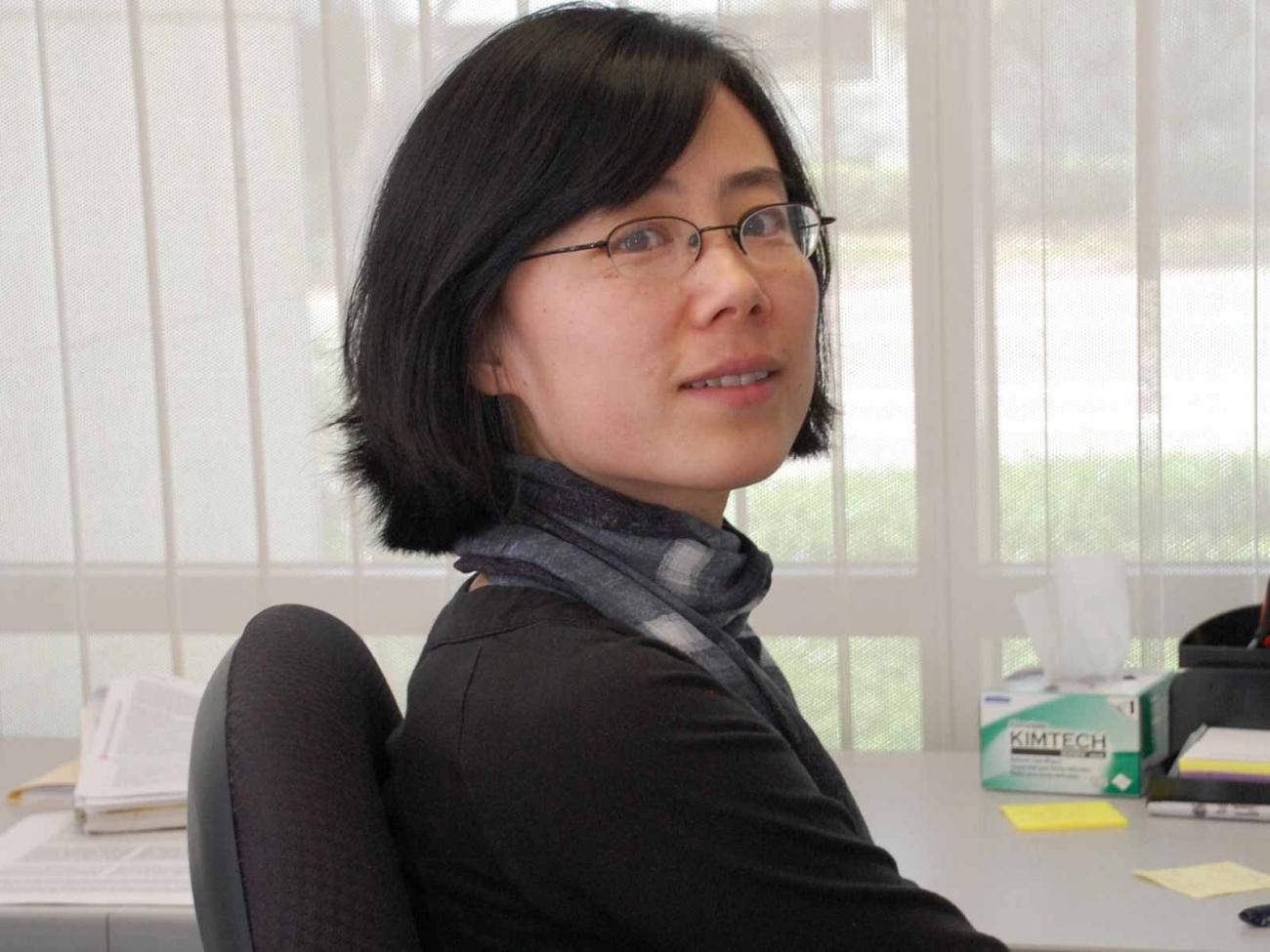

Paloma’s research aims to protect premature babies from brain damage

Newborns have a new scientist in their corner: Paloma Sánchez Pavón, a graduate student in the lab of Jerold Chun, MD, PhD Paloma is working to find a medicine that could protect the still-developing brains of premature babies, which are incredibly delicate and prone to swelling. Called hydrocephalus, the condition is common—affecting one in 1,000 newborns—and repeated brain surgery is the only treatment.

We caught up with Paloma to learn more about what makes her tick, including why she decided to become a scientist and what she wishes people knew about research.

- Did you always know you wanted to be a scientist? When you were a child, did you ever imagine you would be in the role you are today?

I always knew I wanted to become a scientist, but I didn’t imagine I would be in the position I am today. Growing up, I was obsessed with the idea of becoming a marine biologist. I was fascinated by how much we didn’t know about the ocean. My plan was to move closer to the beach and enroll in a program that would allow me to learn more about it. Nevertheless, I soon realized that I was both mesmerized and terrified of the ocean (sharks, especially), and that I would never be able to spend enough time diving and exploring the water, which is what such a career would require. I was still passionate about biology and science in general, so I decided to study the most unknown (and equally unexplored) organ in the human body—the brain. - What do you study, and what is your greatest hope for your research?

I study hydrocephalus, a condition that often affects premature infants. These newborns are extremely fragile and often accumulate fluid in their heads, which can cause brain damage or death. The only treatment is invasive brain surgery, required multiple times throughout individuals’ lives, to insert a shunt in their brains and drain the excess fluid so it is reabsorbed somewhere else in the body. This procedure is extremely uncomfortable for the patients and, like any other surgery, is associated with several risks that endanger their lives. I’m trying to understand the disease so we can find a better, less invasive treatment.

When Paloma isn’t working in the lab, she can be found enjoying one of San Diego’s many beautiful beaches

- What is one scientific question you wish you had an absolutely true answer to?

To answer this question, I will step away from biology and turn to the universe. What is there beyond our galaxy? Will we be able to inhabit other planets? If we have so many things to still learn about the ocean and the brain, the universe is in a completely different category, with so many possibilities ahead of us. - What do you wish people knew about science?

That it is fun. Experiments are about testing limits and going beyond what is known. I think that is really exciting. Also, science advances because we’re constantly asking new questions. Curiosity is what keeps this field in continuous evolution. And never be afraid to ask questions because science can be understood by everybody—it just needs to be explained well. - When you aren’t working in the lab, where can you be found? Where is your happy place?

You will find me at the beach, walking along it or watching a sunset. One of the main reasons why I decided to move to San Diego is because I fell in love with its sunsets. You will also find me having brunch (my favorite American tradition) with my friends or enjoying a beer after work with them, especially around Encinitas or downtown San Diego. - What is the best career advice you have ever received?

Never stop pushing the boundaries of knowledge. A curious mind is what keeps a scientist passionate about their job. Experiments usually don’t work the first time. You have to keep asking new questions and learning from your mistakes. Finishing a project takes time, but every day is unexpected and exciting because you don’t know what you’re going to find. That is the thrilling part about being a scientist. - What do you wish people knew about Sanford Burnham Prebys?

What a great community Sanford Burnham Prebys is. I’ve never been in such a collaborative environment, where you work closely not only with students and postdocs, but also with faculty members. Everyone is always willing to help, whether that is lending reagents or advising about different techniques. As a student, this is what I value the most because it helps me develop as a scientist in an extremely enriching way.

Learn more about our Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences.