The outlook for patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a deadly set of blood cancers that is difficult to treat, has remained dire for decades, especially among patients who are not eligible for bone marrow transplantation.

More than 30% of treated patients will never achieve complete remission using current chemotherapies and, even when chemotherapy treatments work, most patients relapse within five years without a transplant.

While prior research has begun to unravel the genetic underpinnings of the disease, more inquiry is needed to understand the genetic variation within the roughly 15 AML subtypes and how that variation might affect treatment strategies.

“In addition to the one to eight average genetic mutations in AML patients found in traditional sequencing studies, experiments employing high-resolution optical genomic mapping have found approximately 40 to 80 rare genomic structural variants per patient,” says Kristiina Vuori, MD, PhD, Pauline and Stanley Foster Distinguished Chair and professor in the Sanford Burnham Prebys Cancer Center’s Cancer Molecular Therapeutics Program. “We wanted to take these structural variant findings in AML to the next level by connecting them with patients’ sensitivity or resistance to current cancer treatments.”

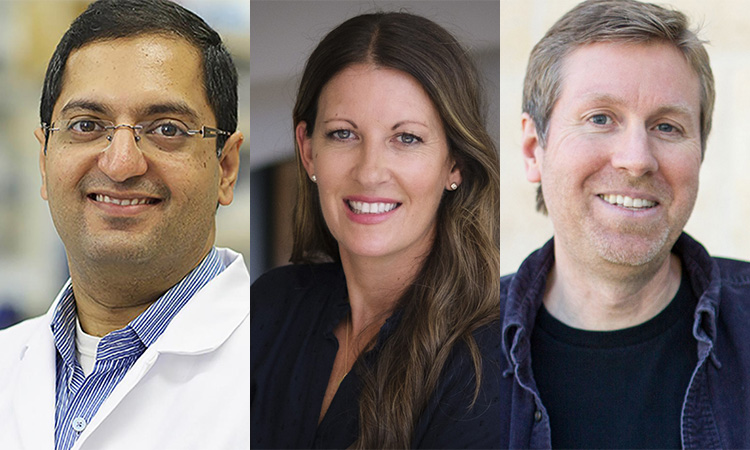

In a paper published January 18, 2024, in Cancers, a multidisciplinary team of biologists, bioinformaticians and clinicians from Sanford Burnham Prebys, Bionano Genomics Inc. and Scripps MD Anderson were the first to associate genomic structural variants (SVs) in AML patients with drug sensitivities.

“SVs are changes to the genome in which sections of 50 or more base pairs in a strand of DNA have been errantly deleted, duplicated, inverted or translocated,” explains Darren (Ben) Finlay, PhD, first author on the manuscript and research associate professor in the Sanford Burnham Prebys Cancer Center.

“Such changes amount to different combinations of DNA gains, losses or rearrangements. When cells use these altered instructions in the DNA to make proteins or carry out other functions, it is like a chef trying to cook with a recipe that is missing steps, has them in the wrong order or includes more or less of the key ingredients.”

Scientists have become more able to find SVs as next-generation genomic analysis technologies and techniques have improved. Research has shown that SVs contribute to the development and progression of cancer, including blood cancers. Of particular concern among SVs are DNA changes that join two otherwise distant genes. This event, called gene fusion, is known to drive certain pediatric and blood cancers.

Finlay, Vuori and colleagues analyzed SVs in samples from 23 AML patients and found their genomes featured 16-45 extremely rare SVs within genes but not seen in healthy volunteers’ samples. The scientists detailed the patients’ SVs using a technique called optical genome mapping. This tool tags DNA in specific locations to create recognizable sequences, unwinds and straightens the genomic DNA for linear scanning, and converts the imaged sequences into digital representations of DNA molecules. Because it directly images DNA rather than relying on algorithmic analyses, optical genome mapping is better than next-generation sequencing at finding SVs throughout the entire genome, especially large SVs, the researchers said.

To begin building the connection between SVs and drug sensitivity, the scientists tested samples from each patient with 120 FDA-approved drugs, and experimental treatments currently in phase III clinical trials. This allowed the researchers to map out how strongly each patient’s sample reacted with each drug.

Next, the investigators used statistical analysis to compare the SVs within the optical genome mapping results with the findings from the drug sensitivity tests. The team found 61 statistically significant interactions between SVs and existing cancer therapies. In one interaction, the group demonstrated that a commonly used AML drug, Idarubicin, and two similar compounds (Daunorubicin and Epirubicin) were more effective in leukemia samples with a specific insertion in a gene that carries the instructions for a signaling enzyme that helps nerves communicate with muscles. These and other examples lend support to the scientists’ hypothesis that optical genome mapping could be used to develop personalized treatment plans that account for patients’ SVs.

“In this pilot study, our hope was to identify structural variants that could be used as new biomarkers for current AML drugs as well as to identify other drugs that could be repurposed to treat leukemia patients,” says Finlay.

“Ensuring patients receive the most effective drugs on the market through personalized treatment and identifying new potential therapies for AML are critically important,” adds Vuori, senior author on the study. “Especially for patients who do not achieve remission with current standard chemotherapies or who are ineligible for bone marrow transplants or clinical trials.”

Cancers 2024, 16(2), 418; https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16020418