Scientists show that an established cancer drug travels to and shrinks some brain tumors, which may lead to new therapies for a disease with few treatments

Brain tumors are the leading cause of cancer-related death in childhood. The deadliest of these tumors are known as high-grade gliomas, with the grade referring to how quickly certain tumors grow and spread throughout the central nervous system.

Treatment options for high-grade gliomas are limited. Surgical removal is typically the first option depending on the tumor size and location. Radiation often follows to kill any remaining cancer cells to prevent another tumor from forming.

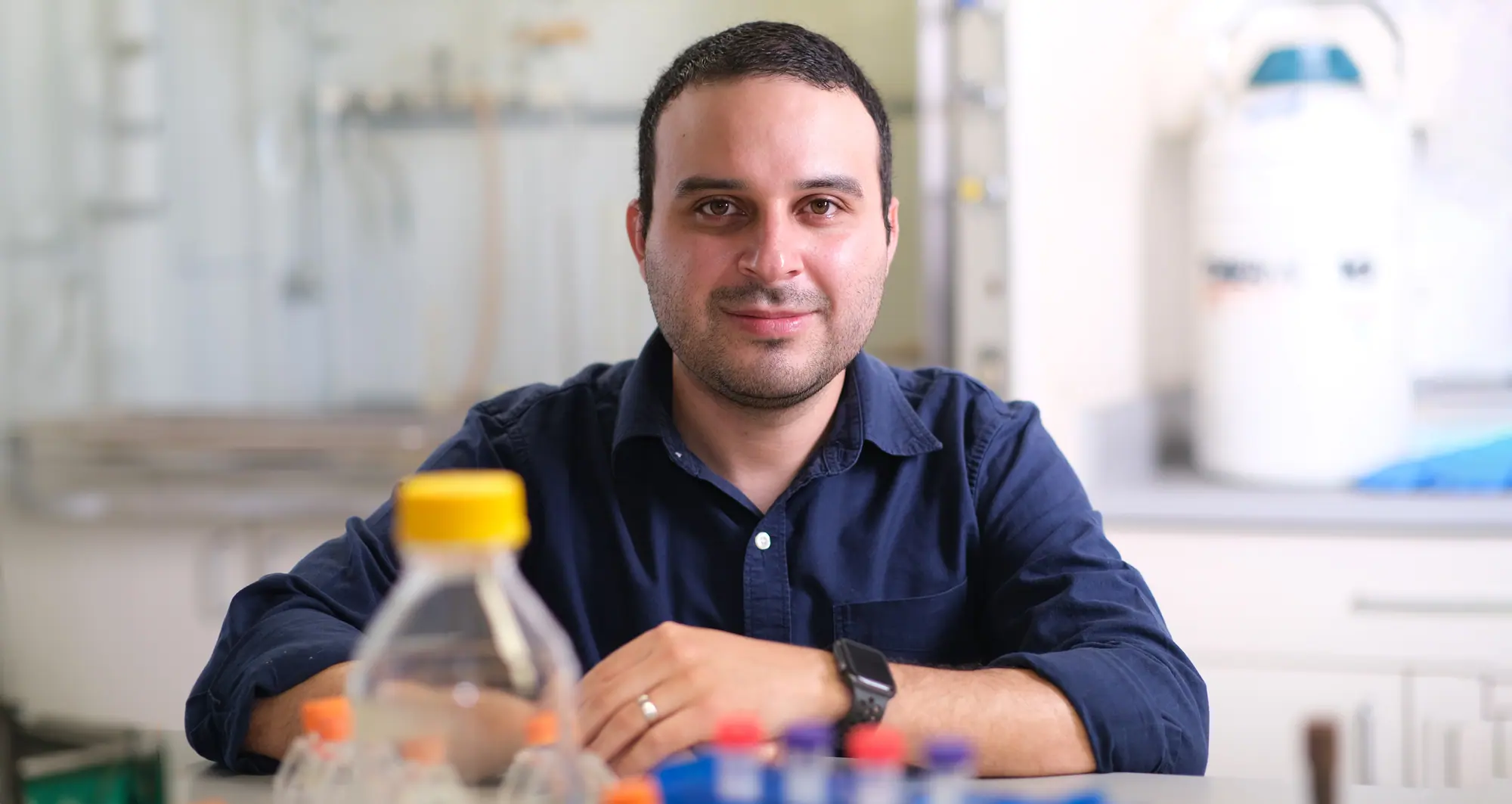

“Drug options to pair with surgery and/or radiation are few and far between,” said Lukas Chavez, PhD, associate professor in the Cancer Genome and Epigenetics Program at Sanford Burnham Prebys. “A big reason for this is the blood-brain barrier being as formidable a boundary as the mythological River Styx.”

The blood-brain barrier can, at times, mean the difference between life and death. It protects the brain and spinal cord from potential toxins and pathogens circulating in the bloodstream. However, in its vigilance, it also blocks beneficial drugs from reaching the brain. This presents a major challenge, since most medications are designed to travel through the bloodstream after being ingested or injected.

Scientists from an international team including Sanford Burnham Prebys, the University of Michigan, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, the Medical University of Vienna and many other institutions published findings March 13, 2025, in Cancer Cell demonstrating that the drug avapritinib could treat certain brain tumor cells. And, like the Styx’s ferryman Charon, the medicine is one of the rare few that can cross the blood-brain barrier known to prevent the passage of more than 98% of small molecule drugs.

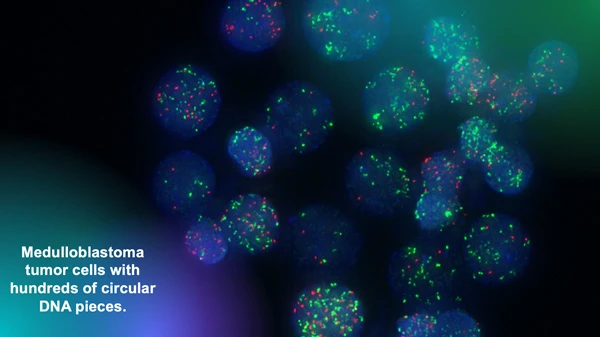

The researchers selected avapritinib—which is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating gastrointestinal and other cancers—after finding it was the strongest commercially available drug for inhibiting the gene Platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA), which is found to be mutated in 15% of high-grade gliomas.

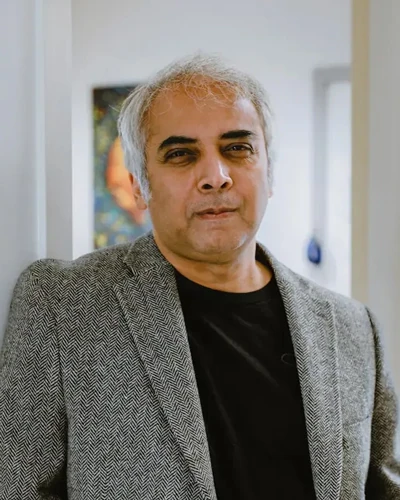

Lukas Chavez, PhD, is an associate professor in the Cancer Genome and Epigenetics Program at Sanford Burnham Prebys.

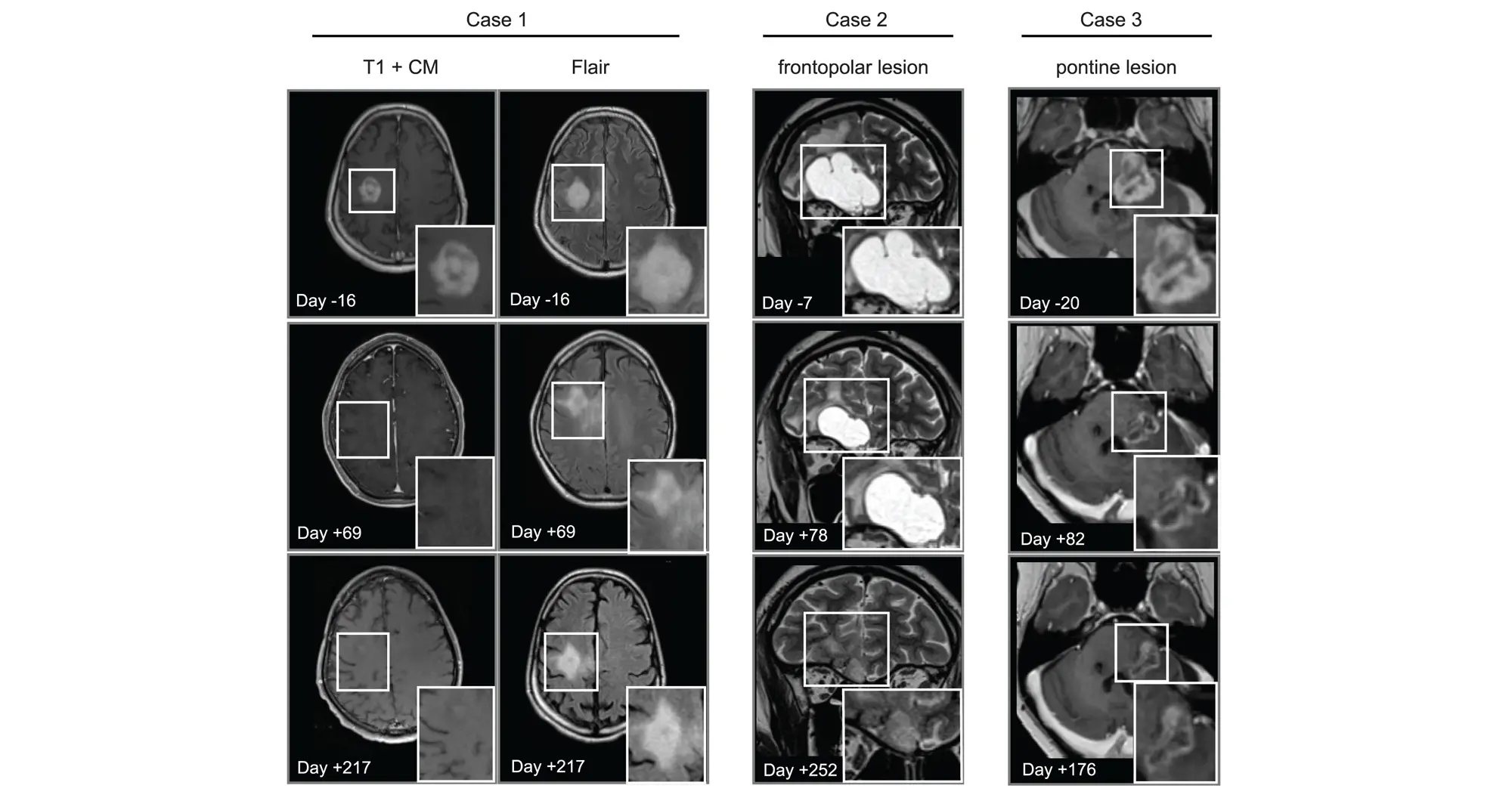

In addition to showing that avapritinib inhibited PDGFRA in cancer cells and mouse brain tumors, the research team tested its effects on eight human pediatric and young adult high-grade glioma patients through a compassionate-use program. The treatment was found to be safe and investigators observed that the drug caused tumors to shrink in three patients.

“More research is needed to better understand how to best repurpose this drug for high-grade gliomas,” said Chavez. “We’ll learn a lot from the ongoing Rover study, a phase 1/2 multicenter trial of avapritinib based on these findings that will include more participants.”

The authors of the new study also highlighted the need to study combining multiple targeted therapies to overcome acquired resistance to any single treatment.

Mariella G. Filbin, MD, PhD, assistant professor of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School and research co-director of the Pediatric Neuro-Oncology Program at the Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center, is the lead contact on the study.

Carl Koschmann, MD, ChadTough Defeat DIPG Research Professor and associate professor of Pediatric Neuro-Oncology at the University of Michigan Medical School, and Johannes Gojo, MD, PhD, head of Pediatric Precision Oncology CNS and ITCC-Lab/Clinical Trials Unit at the Medical University of Vienna, are corresponding authors along with Filbin.

Lisa Mayr, Sina Neyazi, Kallen Schwark and Maria Trissal share first authorship of the study.

Additional authors include:

- Owen Chapman, Sunita Sridhar, Rishaan Kenkre, Aditi Dutta, Shanqing Wang, and Jessica Wang from Sanford Burnham Prebys

- Jenna Labelle, Sebastian K. Eder, Joana G. Marques, Carlos A.O. de Biagi-Junior, Costanza Lo Cascio, Olivia Hack, Andrezza Nascimento, Cuong M. Nguyen, Sophia Castellani, Jacob S. Rozowsky, Andrew Groves, Eshini Panditharatna, Gustavo Alencastro Veiga Cruzeiro, Rebecca D. Haase, Kuscha Tabatabai, Alicia Baumgartner, Frank Dubois, Pratiti Bandopadhayay and Keith Ligon from the Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorder Center and Harvard Medical School

- Liesa Weiler-Wichtl, Sibylle Madlener, Katharina Bruckner, Daniel Senfter, Anna Lammerer, Natalia Stepien, Daniela Lotsch-Gojo, Walter Berger, Ulrike Leiss, Verena Rosenmayr, Christian Dorfer, Karin Dieckmann, Andreas Peyrl, Amedeo A. Azizi, Leonhard Mullauer, Christine Haberler and Julia Furtner from the Medical University of Vienna

- Jack Wadden, Tiffany Adam, Seongbae Kong, Madeline Miclea, Tirth Patel, Chandan Kumar-Sinha, Arul Chinnaiyan and Rajen Mody from the University of Michigan Medical School

- Alexander Beck from Ludwig Maximilians University Munich

- Jeffrey Supko and Hiroaki Wakimoto from Massachusetts General Hospital

- Armin S. Guntner from Johannes Kepler University

- Hana Palova, Jakub Neradil, Ondrej Slaby, Petra Pokorna and Jaroslav Sterba from Masaryk University

- Louise M. Clark, Amy Cameron and Quang-De Nguyen from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

- Noah F. Greenwald and Rameen Beroukhim from the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard

- Christof Kramm from University Medical Center Gottingen

- Annika Bronsema from University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf

- Simon Bailey from Great North Children’s Hospital and Newcastle University

- Ana Guerreiro Stucklin from University Children’s Hospital Zurich

- Sabine Mueller from the University of California San Francisco

- Mary Skrypek from Children’s Minnesota

- Nina Martinez from Jefferson University

- Daniel C. Bowers from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center

- David T.W. Jones, Natalie Jager from Hopp Children’s Cancer Center Heidelberg

- Chris Jones from the Institute of Cancer Research