A method for studying human neurons could help researchers develop approaches for treating Alzheimer’s, schizophrenia and other neurological diseases

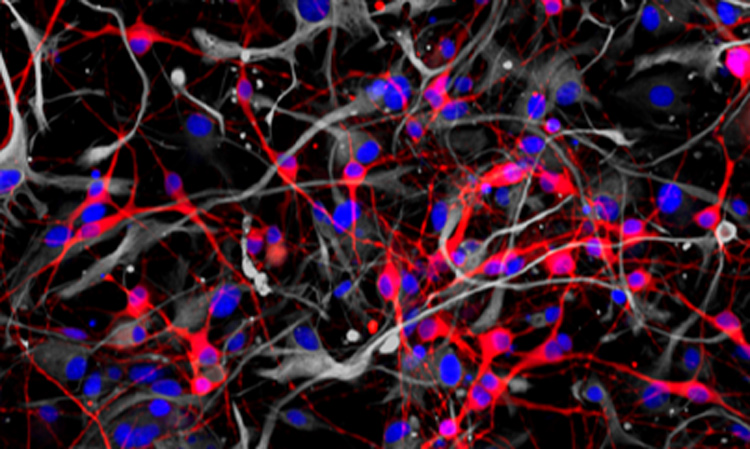

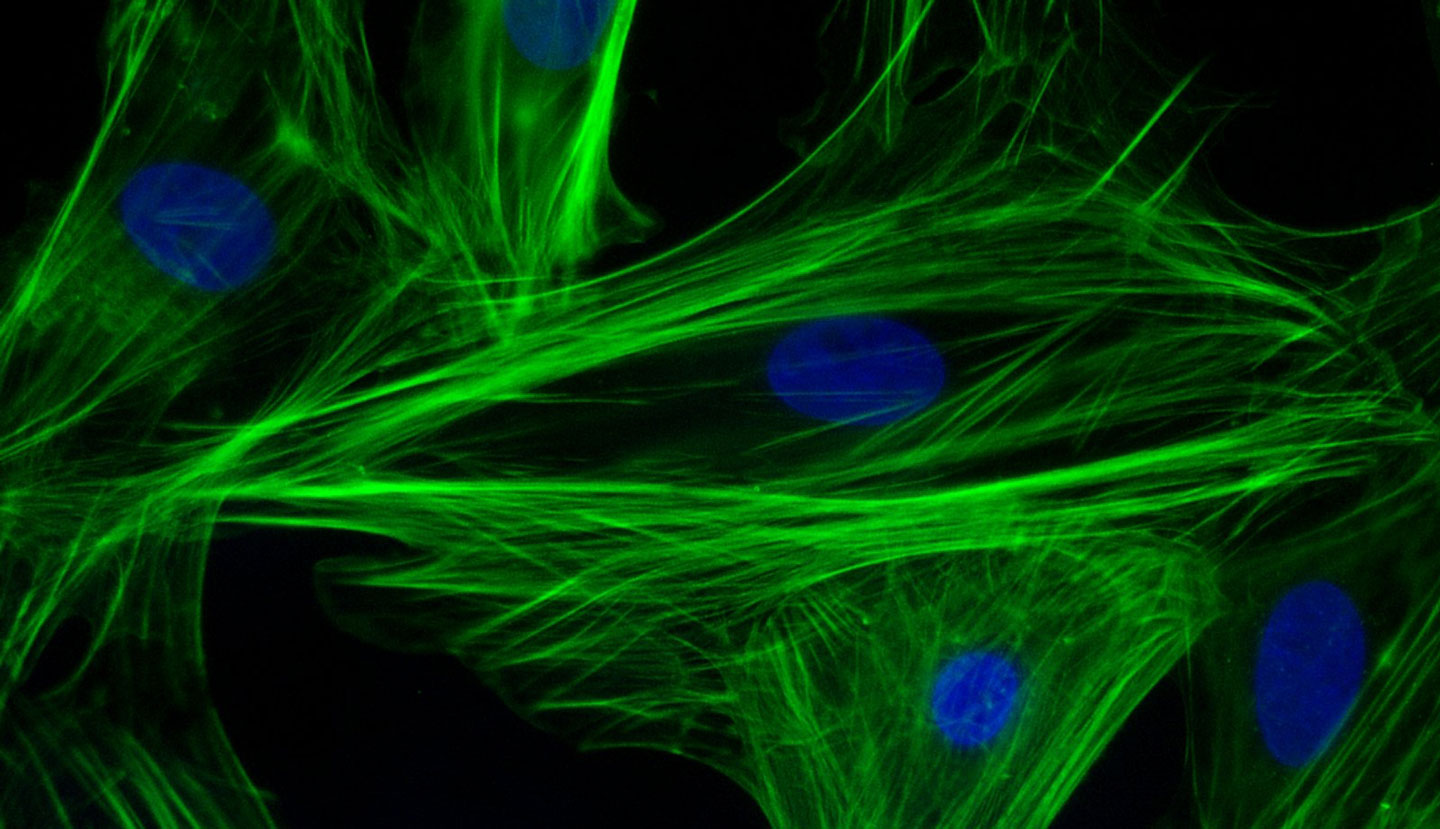

Researchers from the Conrad Prebys Center for Chemical Genomics have developed a procedure to use neurons derived from human stem cells to study the biological processes that control learning and memory. The method, described in Stem Cell Reports, uses electrodes to measure the activity of neuronal networks grown from human-induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). The procedure tracks how synapses—the connections between neurons—strengthen over time, a process called long-term potentiation (LTP).

“Impaired long-term potentiation is thought to be central to many neurological diseases, including Alzheimer’s, addiction and schizophrenia,” says senior author Anne Bang, PhD, director of Cell Biology at the Prebys Center. “We’ve developed an approach to study this process in human cells much more efficiently than current methods, which could help trigger future breakthroughs for researchers working on these diseases.”

LTP helps our brain encode information, which is what makes it so critical for learning and memory. Impairment of LTP is thought to contribute to neurological diseases, but it has proven difficult to verify this hypothesis in human cells.

LTP helps our brain encode information, which is what makes it so critical for learning and memory. Impairment of LTP is thought to contribute to neurological diseases, but it has proven difficult to verify this hypothesis in human cells.

Anne Bang, PhD, director of Cell Biology at the Prebys Center.

“LTP is such a fundamental process,” says Bang. “But the human brain is hard to study directly because it’s so inaccessible. Using neurons derived from human stem cells helps us work around that.”

Although LTP can be studied in animals, these studies can’t easily account for some of the more human nuances of neurological diseases.

“A powerful aspect of human stem cell technology is that it allows us to study neurons produced from patient stem cells. Using human cells with human genetics is important in these types of tests because many neurological diseases have complex genetics underpinning them, and it’s rarely just one or two genes that influence a disease,” adds Bang.

To develop the method, first author and Prebys Center staff scientist Deborah Pré, PhD, grew networks of neurons from healthy human stem cells, added chemicals known to initiate LTP and then used electrodes to monitor changes in neuronal activity that occurred throughout the process.

The method can run 48 tests at once, and neurons continue to exhibit LTP up to 72 hours after the start of the experiment. These are distinct advantages over other approaches, which can often only observe parts of the process and are low throughput, which can make getting results more time consuming.

For this study, the researchers used neurons grown from healthy stem cells to establish a baseline understanding of LTP. The next step is to use the approach on neurons derived from patient-derived stem cells and compare these results to the baseline to see how neurological diseases influence the LTP process.

“This is an efficient method for interrogating human stem cell–derived neurons,” says Bang. “Doing these tests with patient cells could open doors for researchers to discover new ways of treating neurological diseases.”