Thanks to a generous grant from The Conrad Prebys Foundation, a diverse group of early-career researchers will gain hands-on experience in drug discovery and translational medicine.

A new educational program at Sanford Burnham Prebys has welcomed a diverse group of early-career scientists to learn how to transform research discoveries into treatments for human diseases. The program was made possible by a generous grant from The Conrad Prebys Foundation as part of its mission to increase the diversity of San Diego’s biomedical workforce.

“Our mission at The Conrad Prebys Foundation is to create an inclusive, equitable and dynamic future for all San Diegans,” says Grant Oliphant, CEO at The Conrad Prebys Foundation. “San Diego is one of the top areas in the country for biomedical research, and we’re pleased to partner with Sanford Burnham Prebys to help strengthen the pipeline of diverse talent in life sciences research.”

Graduate students and postdoctoral fellows selected for the program will complete projects at the Institute’s Conrad Prebys Center for Chemical Genomics (Prebys Center), the nation’s leading nonprofit drug discovery center. The Prebys Center specializes in finding new medicines for diseases with a substantial unmet medical need in order to develop better therapies.

“Thank you to The Conrad Prebys Foundation. I am beyond grateful for their support,” says predoctoral Prebys fellow Michael Alcaraz, who will complete his project on the links between aging and brain disease with Professor Peter D. Adams, PhD, and Steven Olson, PhD, executive director of Medicinal Chemistry at the Prebys Center.

To help fulfill the Foundation’s mission, Sanford Burnham Prebys students and postdocs from historically underrepresented groups were encouraged to apply for the new program.

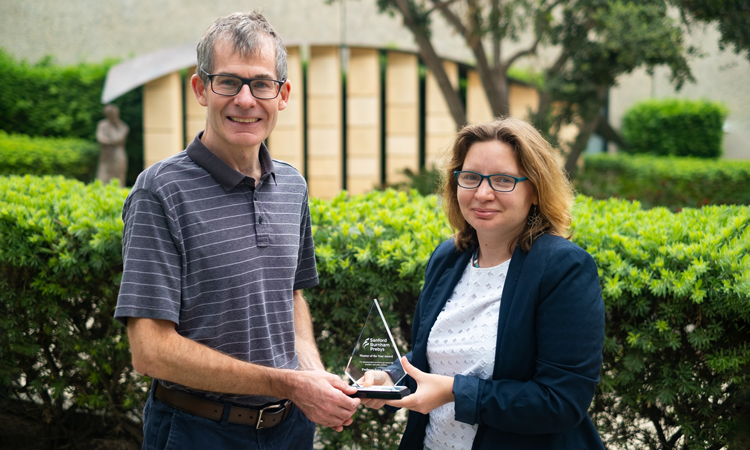

“Promoting diversity in the biomedical workforce is a founding principle of our educational program,” says Alessandra Sacco, PhD, vice dean and associate dean of Student Affairs in the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at Sanford Burnham Prebys. Sacco will oversee the new program alongside Dean Guy Salvesen, PhD, and Professor Michael Jackson, PhD

“Working actively to train people from all backgrounds gives opportunities to people who may not otherwise have had them—and it also improves the quality of the research itself,” she adds.

“Translational research is one of the biggest priorities in biomedicine right now because it’s how we turn discoveries into actual medicines,” says Sacco. “This program gives students and postdocs an opportunity to build the skills they need for translational research jobs in academia or industry.”

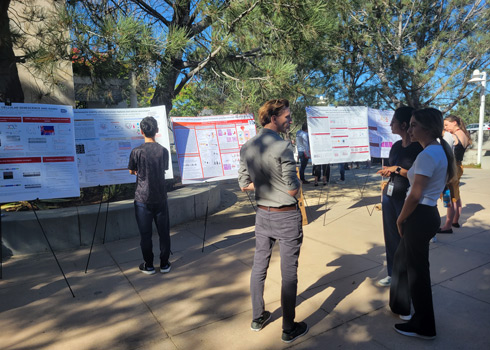

The fellowship will culminate in a final symposium next spring, where the fellows will present their research to their peers and to the wider community.

“I’m looking forward to gaining more experience and making my contribution to the translational science at the Prebys Center,” says predoctoral Prebys fellow Merve Demir, who will complete a structural biochemistry project with Assistant Professor Jianhua Zhao, PhD, and Eduard Sergienko, PhD, director of Assay Development at the Prebys Center.

The full list of fellows includes:

Postdoctoral Fellows

– Karina Barbosa Guerra [Deshpande Lab, Ed Sergienko co-mentor]

“SGF29 as a novel therapeutic target in AML”

– Merve Demir [Zhao Lab, Ed Sergienko co-mentor]

“Structural studies of MtCK and GCDH enzyme drug targets”

– Jerry Tyler DeWitt [Haricharan Lab, TC Chung co-mentor]

“Investigating the unique molecular landscape of ER+ breast cancer in black women”

– Alicia Llorente Lope [Emerling Lab, Ian Pass co-mentor]

“Exploring PI5P4Kγ as a novel molecular vulnerability of therapy-resistant breast cancer”

– Van Giau Vo [Huang Lab, TC Chung co-mentor]

“Identifying enhancers of SNX27 to promote neuroprotective pathways in Alzheimer’s disease and Down Syndrome”

– Xiuqing Wei [Puri Lab, Anne Bang co-mentor]

“Selective targeting of a pathogenetic IL6-STAT3 feedforward loop activated during denervation and cancer cachexia”

Predoctoral Fellows

– Michael Alexander Alcaraz [Adams Lab, Steven Olson co-mentor]

“Activating the NAMPT-NAD+ axis in senescence to target age-associated disease”

– Shea Grenier Davis [Commisso Lab, Steven Olson co-mentor]

“Examining PIKfyve as a potential therapeutic target in pancreatic cancer”

– Patrick Hagan [Cosford Lab, Ian Pass co-mentor]

“Discovery and development of novel ATG13 degrading compounds that inhibit autophagy and treat non-small-cell lung cancer”

– Texia Loh [Wang Lab, Ed Sergienko co-mentor]

“Investigating the role of HELLS in mediating resistance to PARP Inhibition in small-cell lung cancer”

– Michaela Lynott [Colas Lab, TC Chung co-mentor]

“Identification of small molecules inhibiting ATF7IP-SETDB1 interacting complex to improve cardiac reprogramming efficiency”

– Tatiana Moreno [Kumsta Lab, Anne Bang co-mentor]

“Identifying TFEB/HLH-30 regulators to modulate autophagy in age-related diseases”

– Utkarsha Paithane [Bagchi Lab, TC Chung co-mentor]

“Identification of small-molecule enhancers of Honeybadger, a novel RAS/MAPK inhibitor”